Though I grew up watching Perry Mason on television, I didn’t crack the spine of my first Erle Stanley Gardner novel—The Case of the Rolling Bones (1939)—until two years ago. When I did, what a coup de foudre. On the page, Perry Mason is a sexy, sassy smarty-pants, the strong silent type. His mind careens at a thousand miles an hour, propelled by endless pacing. He’s a heroic crusader who wouldn’t seem out of place pulling up a chair at King Arthur’s round table.

A typical Perry Mason novel moves like a cataract forced through a crazy straw. Gardner never claimed to be a brilliant stylist, calling himself a “Fiction Factory.” He said, “I want to establish a style of swift motion. . . . characters who . . . sprint the whole darned way to the goal line.” That pace echoed his early years as a lawyer, when, he reported, he’d try “to keep the case moving with such bewildering rapidity that it would be hard for the prosecutor or the judge to keep abreast of the various legal problems.”

His format is comfortingly familiar: someone (often a damsel in distress) arrives in Mason’s office with an improbable story, begging for help. Mason, the ultimate curious cat, a man constitutionally allergic to boredom, takes the case.

No matter what he’s hired to do (keep a rich old man out of an asylum, defend a woman falsely accused of soliciting, settle an inheritance claim, locate a missing relative), before long there’s a murder, and the true mission emerges: fight for truth and justice on behalf of his wrongly accused client.

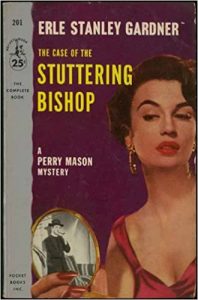

In The Case of the Stuttering Bishop (1937), Mason outlines his credo: “I’m not merely a paid gladiator fighting for those who have the funds with which to employ me. I’m a fighter, yes, and I like to feel that I fight for those who aren’t able to fight for themselves, but I don’t offer my services indiscriminately. I fight to aid justice.”

Gardner’s pact with readers promised that Mason’s clients, whatever else they’ve done, would always be innocent of murder. That way, when the lawyer plays things fast and loose, we can revel in every wild scheme without troubling our consciences one little bit. He explained, “I write to make money, and I write to give the reader sheer fun. People derive moral satisfaction from reading a story in which the innocent victim of fate triumphs over evil. They enjoy the stimulation of an exciting detective story. Most readers are beset with a lot of problems they can’t solve. When they try to relax, their minds keep gnawing over these problems and there is no solution. They pick up a mystery story, become completely absorbed in the problem, see the problem worked out to final and just conclusion, turn out the light and go to sleep.”

Mason is as much detective as lawyer, but typically the payoff is a courtroom showdown that sees Mason clear his client’s name and pull a “J’accuse!” with the guilty party. These justifiably famous showdowns are rich in legal detail, offering an education in American law of the era. Legend has it that Gardner, whose fan base boasted numerous judges and lawyers, only made one mistake in his prolific career, when he allowed the beneficiary of a will to witness it as well.

The Man Behind the Factory

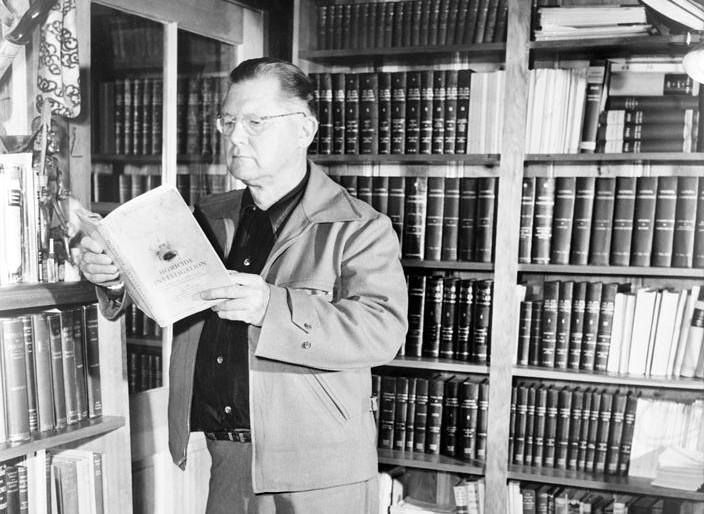

When he died, in 1970, Erle Stanley Gardner was the best-selling American fiction author of the century. He wrote 100,000 words a month for some fifty years. His New York Times obituary cited sales of more than 170 million books in the US alone, and reported his paperback publisher saying that in the mid 1960s they sold 2,000 Gardner books an hour, eight hours a day, 365 days a year.

From the 1920s on, Gardner produced an avalanche of pulp stories, novellas, cowboy yarns, science fiction, travelogues and several mystery series, on top of the 80 Perry Mason novels that cemented his fame and fortune, and won him fans such as Einstein (reported to be reading a Perry Mason novel on his deathbed), Harry S. Truman, and Pope John XXIII.

Oh, and in 1949, Evelyn Waugh told interviewers that Gardner was America’s best writer. People dismissed this as a joke. It wasn’t. Writing to Gardner in 1960, Waugh called himself “one of the keenest admirers of your work.” People still scoffed, yet when it was put to his widow, Laura, she confirmed that Evelyn had read every book, and pressed them on the entire family.

From left to right: Raymond Barr, Barbara Hale, Erle Stanley Gardner, William Hopper.

From left to right: Raymond Barr, Barbara Hale, Erle Stanley Gardner, William Hopper.

Gardner was born in Massachusetts in 1889, and raised in California. He and his father often hit out for the open road, a habit that endured throughout his life: Gardner was happiest outdoors, alone, communing with nature.

According to Francis Nevins, in Samurai at Law: Erle Stanley Gardner (shared with me by the author), as a kid Gardner earned money boxing in unlicensed matches. “His interest in the law seems to have grown out of hunting for loopholes in the California statutes that made prizefighting illegal. After completing high school in 1909 he was admitted to Valparaiso University in Indiana but was soon expelled for slugging a professor.”

In Oxnard, California, he worked in law offices and studied, and in 1911, passed the state bar exam—without ever attending university or law school. Nevins writes, “Over the next twenty years he discovered that litigation was a form of combat at which he could excel, and he earned a reputation as one of the state’s most flamboyant trial lawyers.”

He often championed underdogs. One legendary tale concerns twenty Chinese men accused of running an illegal lottery. Gardner quietly had the men switch places at their various businesses. When the police arrived to book them, the men were naturally misidentified. At the trial Gardner pointed out this discrepancy, insisting that if the cops couldn’t tell their suspects apart, the eye-witnesses must be equally unreliable. The case was dismissed.

Another time he sprang a client on a technicality. Certain he’d be re-arrested, Gardner sent the man to the next county, swore a citizen’s complaint against him, and had him plead guilty to violating state gambling laws. A small fine was paid, and that was that. Back in Oxnard, the city attorney did re-arrest the man—prompting Gardner to flourish court records and argue, successfully, that his client could not be tried twice for the same offense.

Later still, Gardner founded The Court of Last Resort, dedicated to seeking justice for those who were falsely imprisoned.

There’s an argument that author and character eventually merged. They sure sound alike. In The Case of the Stuttering Bishop Mason says: “I hate routine. I hate details. I like the thrill of matching my wits with crooks. I like to have people lie to me and catch them in their lies. I love to listen to people talk and wonder how much of it is true and how much of it is false. I want life, action, shifting conditions. I like to fit facts together, bit by bit, like the pieces of a jigsaw puzzle.”

The men shared a restless sense of adventure, idealism, and a passion for justice. Mason paces back and forth to spark his brain, when composing, Gardner planted himself in a rocking chair, teetered it across the carpet, then went back across the room to set off again.

Interesting, then, that Gardner, who had creative control of the television series, clapped eyes on Canadian actor Raymond Burr—there auditioning for the role of DA Hamilton Burger—and said, “That’s him, that’s Perry Mason!”

Prolific and Punchy

Gardner would put in a full day’s legal work, then around 10pm, start writing, working until 1 or 2am. He slept about three hours a night, and wrote for a couple of hours before heading to the office. Gardner admits his early output wasn’t great, but he built up a head of steam, becoming a regular contributor to pulp magazines such as Black Mask and Top Notch.

In the early 1930s he contacted William Morrow and Company about a series featuring a lawyer: “I want to make my hero a fighter, not by having him be ruthless with women and underlings, but by having him wade into the opposition and battle his way through to victory. . . . the character I am trying to create for him is that of a fighter who is possessed of infinite patience. He tries to jockey his enemies into a position where he can deliver one good knockout punch.”

The Case of the Velvet Claws (1933) introduced Mason, PI Paul Drake, and Della Street. They were slightly different in those early books, Perry and Della were loucher. Mason was quick with his fists, more interested in his fee than anything else. Considering those early books were written at the height of the Depression, this isn’t too surprising.

Gardner’s ambition was to publish in magazines with good reputations and deep pockets. When editors at The Saturday Evening Post, who found Mason “tawdry,” asked him to knock off the rough edges, he was happy to comply, working closely with them on The Case of the Lame Canary (1937). They paid a whacking $15,000 for the serialization.

Nevins writes, “Before long, Mason was a fixture in the Post, and the magazine bought and published Perry Mason serials until the early 1960s. Hollywood studios purchased rights to various novels, and seven uneven Perry Mason movies were produced. A highly successful Perry Mason radio drama broadcast for almost ten years. And of course the Perry Mason television series of the late 1950s and early 1960s starring Raymond Burr attracted millions of weekly viewers. By mid-century Perry Mason was one of the most successful pop cultural figures in American history.”

What Does This Have To Do With Chivalry?

As I sped my way through The Case of the Rolling Bones, and the next story, and the next, gobbling them like popcorn, I questioned why I found Mason compelling. Then I found a piece in The Washington Examiner, likening the Mason novels to “classic romance literature: knightly tales of quests and noble deeds.” But of course! Central to these novels is the idea of loyalty—Mason’s loyalty to clients and to the truth; Drake and Street’s loyalty to Mason. Such loyalty is integral to the code of King Arthur’s round table, and the Three Musketeers’, whose motto is “All for one and one for all.”

Perry Mason—incorruptible, clever, dedicated, dogged—slots nicely into the Arthurian mould. His “grail quest” is the pursuit of justice on behalf of innocents unable to defend themselves; his jousting field is a courtroom. He is never unseated.

Surely everyone wants a knight in shining armor on their side. Consider this article about choosing the right lawyer, by Beverley Lewis, proposing that the seven knightly virtues form a lawyer’s “code of chivalry.” Those virtues are courage, justice, mercy, generosity, faith, hope, and nobility.

Let’s Not Forget Courtly Love

Then there is the case of Perry Mason and the women.

I approached Gardner with trepidation, knowing he wrote from the 1930s onward, and began with pulp fiction. I prepared myself for sexist, misogynistic depictions of women. How wonderful to be wrong! The books empathize with women, especially working women. Gardner’s descriptions are fairly basic, but he gives equal time to male and female attributes, and female motivations and ambitions carry equal weight as men’s.

And while Paul Drake and his operatives are an essential weapon in Mason’s arsenal, Della Street is unmistakably the most important person in his life. On the first page of The Case of the Velvet Claws (1933), our introduction to all that will follow, she warns Perry there’s a woman in the outer office saying she’s Mrs Eva Griffin, but “She looks phoney to me.”

Mason doesn’t dismiss her intuition, or reprimand her for speaking her mind. He listens. The message is clear: he depends on and values this woman, whose “keenly appreciative eyes [see] far below the surface.”

The inspiration for Della Street came from Gardner’s life. In 1912, he eloped with a secretary, Natalie Talbert, who worked in the same law office. They had a daughter. Marriage to a man who worked all day and wrote all night couldn’t have been easy. On top of that he craved the open air, buying a succession of motor homes which he’d park in remote spots in order to hole up and write. Later, he bought land, establishing a series of boltholes.

Around 1930, Gardner hired three sisters as his secretaries, Jean, Ruth, and Peggy, and, much later, in 1963, a researcher called Betty Burke. Gardner said Della was a composite of these sisters, though after his death, his daughter laid claim to her mother’s strong, early influence, pointing out that she’d been a legal secretary when the couple met.

By the 1930s the Gardners lived apart, and around 1933 he gave up law to write full time. He and his fleet of secretaries would head into the desert for weeks at a time, while he composed his books. He took all or some of the team on his peregrinations around the US, and overseas, as well.

Betty Burke would later say, “Erle trained Jean to keep track of everything. She was always with him. But it was like a father-daughter relationship. Everybody tried to make a big romance out of it, which always bored the daylights out of me. Because Erle Stanley Gardner wasn’t running around romancing anyone. He was a jolly, huggable old man who loved to talk. But he was also very businesslike. And no one bothered him when he was working. We all knew that.”

Be that as it may—or may not—though he never divorced Natalie, and by all accounts, they remained amicable, in 1968, after his wife died, Gardner married Jean.

As for Perry and Della, they’re on intimate terms—forever dining out and dancing, and even visiting Hawaii together—but sex is never spelled out. At the end of The Case of the Velvet Claws Perry kisses Della, but I’ve yet to come across another such moment in my reading. The reality is a lot sexier, an endless series of smoldering looks, crushing hugs, shoulder rubs, hands held, and the like.

This united-yet-apart model mirrors the tradition of courtly love, which supposes forbidden yet adamantine love between a knight and his lady. Perry proposes to Della several times, and Street always deflects the suggestion.

In The Case of the Rolling Bones, time spent in a suspect’s cosy apartment makes the lawyer sentimental:

“Perry Mason’s hand unconsciously sought Della Street’s, gently imprisoned the fingers. ‘Gosh, Della. . . it almost seems as if this place had been made for us.’

She moved her other hand to stroke the back of his well-shaped strong fingers gently, ‘Nix on it, Chief,’ she said gently. ‘You could no more live a domestic life than you could fly. You’re a free-lance, happy-go-lucky, carefree, two-fisted fighter. You might like home for about two weeks and then it would bore you stiff. At the end of four months you would feel it was prison.’

‘Well,’ Mason said, ‘this is part of the first two weeks.'”

In The Case of the Lame Canary, she refuses him by saying, “We’re getting along swell the way it is. You’d establish me in a home somewhere as your wife. Then you’d get a secretary to help you with your work. The first thing you knew, you’d be sharing excitement and experiences with the secretary and I’d be entirely out of your life. No, Mr. Perry Mason, you aren’t the marrying kind. You live at too high a speed. You’re too wrapped up in mysteries.”

That sounds a lot like the Erle-Natalie-Jean triangle to me.

Let’s face it, Will They/Won’t They tension is infinitely sexier than a depiction of marriage. It’s the reason why most fairy tales and movies end when the hero gets the girl. Gardner had this in mind when he said, “How little you know of human nature. Those who want Della to sleep with her boss are those who are afraid she isn’t, and those who think she shouldn’t are the ones who are certain she is.” More bluntly, he said, “If [Perry] married Della, he would lose his sex appeal.”

Perry Mason is a Twentieth Century update of the “parfit gentil knight.” He has no family and no history. He just is.

I can’t get enough of him.