On October 4, 2022, legendary author Peter Robinson, creator of the long-running Inspector Banks series, passed away after a brief illness. Beginning with Gallows View in 1987, Robinson delivered a novel in the series, or short story collection, almost every year until his death. He also managed to find the time to write three stand-alones. All told, he completed 34 books, 31 of them either Inspector Banks novels or related short story collections.

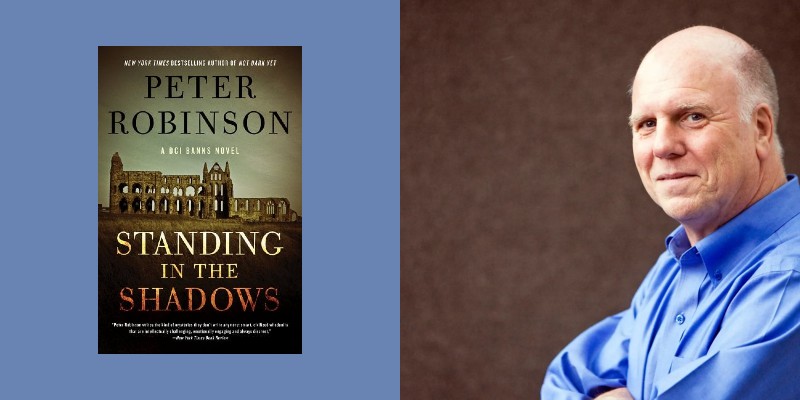

His new, posthumously published Banks novel, Standing in the Shadows is now available. And while all of Robinson’s Banks stories can be read out of order, this book also completes the “Zelda” trilogy, and represents some of Robinson’s darkest work.

Sheila Halladay, Peter’s wife, to whom he dedicated almost every novel, graciously agreed to an interview and gives his readers wonderful insight into his approach to his craft, his love of all kinds of music and literature and an overall picture of an exceedingly talented and warm human being.

*

“Peter had a very literary mind,” says Halladay, “after all he did have a PhD in English literature, so I think that he read not only for pleasure but would be analytical and try to learn from the styles of other authors. Once he started writing his own manuscript, he would stop reading crime fiction, because he was wary of getting into the unconscious habit of imitating other writers…He was constantly casting about for ideas for a book. Because he had such a wide range of interests, the basis of the plot could come from anything that piqued his interests. Peter always carried a notebook and was constantly making notes. I would often find scratching on bits of paper of ideas, a phrase of a description, or a thought for a character, strewn around the house.”

With Standing in the Shadows, Robinson returned to one of his favorite stylistic techniques, the use of a first-person narrative and Banks written in the third. “He liked experimenting with the concept of two stories, in different time periods with different characters, that over the course converges into one narrative.”

In Standing in the Shadows, the historical aspect of the plot is set in 1980 in Leeds, West Yorkshire, a time and place of both radical students and the terror of the Yorkshire Ripper. The plot is complex although never convoluted as it moves back and forth through the decades.

Beginning in 1980, a student named Nick has been dumped by his strident activist girlfriend Alice for a flashier sophisticated man, Mark. When Alice turns up dead in a local park, Nick is suspected – is he maybe even the Ripper? Meanwhile, Mark vanishes at the same time. Fast forward to 2019. Banks and his team are called to investigate a skeleton – a very deteriorated one — found by a group of archeologists excavating a lonesome plot of land attached to a nearby field where a shopping center is to be built. How Robinson adroitly and convincingly ties these two deaths together is yet another example of his gifts for plotting amid diverse time periods and a disparate set of suspects and supporting cast.

Halladay on how he put it all together: “While Peter was not a “plotter” in the sense of working out every scene in advance on cue cards or post-it notes, he did a lot of thinking about the book and wouldn’t start writing until he had a general idea of the overarching plot of the book.

Because he didn’t write detailed outlines before he started writing and never knew exactly where the plot was going. As he was writing, he continuously researched details that were specifically needed to advance the plot. For, example he might need to know the differences in dental practice between the UK and North America, or research of different types of guns, or perhaps blood spray patterns or buttons on uniforms from World War II.

“He used to say that the details of police procedure should not get in the way of a good plot,” notes Halladay. “So latterly he would write a scene first and then check with the experts to see if it could have happened that way. For example, one time he was told that a person of Banks’ rank would probably not head up a national investigation. Not a problem, Banks’ supervisor became incapacitated, and Banks got a promotion.

“Peter was a very disciplined and committed writer and he always met his deadlines. Once Peter started on a manuscript, he was pretty steady. While he was flexible and didn’t commit to a strict schedule, he would generally concentrate on writing for three to four hours in the morning. I was very lucky that he did not wake up in the middle of the night to frantically write. He would tease that if the writing was going well in the morning, he would go back to it in the afternoon and if it was not going well, he would go to the pub.

“As Peter was heading towards writing the conclusion of the book, his pace of writing would pick up. Because he did not plot out the books in advance, he had to keep all of the strands of the main plot, secondary stories etc. in his head. It was a like giant puzzle that he had to put together. The actual murderer was not particularly important to Peter and he would usually be over half way through the manuscript when he would announce that he knew ‘who did it’. He always found it amusing when people would tell him the page when they knew who the murderer was, and he would tell them that he didn’t know until much later.”

A sense of place pervades all of Robinson’s Inspector Banks novels, and the primary setting is Yorkshire. In Standing in the Shadows, Banks goes for the first time to the landscape where the skeletal corpse is discovered, and is struck by the trees on the property. “They were odd-looking trees, not majestic and wide spreading, but squat, black, knotty and gnarled, with thick trunks and branches twisted into strange shape, like headless torsos or Prometheus trying to break free from his chains. Most still had a few leaves clinging to their branches and twigs. Banks thought they seemed creepy in the louring twilight and half expected one of them to start moving like the Ents in Lord of the Rings.”

Halladay and Robinson traveled extensively over their marriage. “While Eastvale (the village setting of the stories) and the surrounding areas were clearly fictional, they were in fact based on actual places. When he first showed me around the Dales he would point out the spot where the body was discovered in a Dedicated Man or The Hanging Valley. We went to Thrushcross to see a dried-up reservoir and that became the basis for In a Dry Season. Or a walk around the abandoned racecourse north Richmond, led us into a remote dale that formed the setting for Before the Poison.”

In terms of the violence in the stories, for the most part, Halladay says. it “…usually involved finding the body in a specific place. Most of the violence in Peter’s books was offstage, and while he would rarely actively describe violent acts he would often start books by vividly describing the gruesome effects of violent acts on the victim. He often said that one of the most interesting characters in his crime fiction was the one who wasn’t actively there – the dead victim. What was it in their past that led to someone wanting to kill them?”

But in the previous two, Many Rivers to Cross and Not Dark Yet, the other key protagonist, Zelda, a previously sex-trafficked woman who lived with a friend of Banks’, seeks revenge on the abusers from her youth. In Not Dark Yet she does not mess around during an oral rape attempt by a man armed with a knife: “She closed her eyes, felt the cold steel on her skin, felt his hand press against the back of her neck, pulling her forward. ‘Open your mouth’. Zelda opened her mouth and felt him enter her. She almost gagged but managed to stop herself. Instead, she offered a prayer to the God she didn’t believe in and bit down as hard as she could.” Zelda mixes it up brutally as well in Many Rivers to Cross, when she drugs a captor and finishes him off with a knife. It’s as grim and grisly as Robinson gets.

Halladay suggests that perhaps this almost unyielding somberness in the final three books may have come from coping with the pandemic. “While he started the trilogy prior to the pandemic, he continued writing throughout the time of social isolation. As you pointed out, the Zelda books were quite “dark”. While some writers commented that they got a lot of writing done during this time, Peter personally had difficulty concentrating on writing. He wasn’t by any means clinically depressed, but he often felt down, particularly when he thought of the state of world politics. But he got over it and I think that you will find when you read his last book, Standing in the Shadows, that Peter and his character Banks (although he was always quick to point out that they were not the same people), reached some sort of state of contentment.”

A particular joy of the series for many readers is Robinson’s use of a very wide range of music that Banks listens to. From obscure folksingers to punk bands to classical composers, opera—Robinson demonstrates a depth of knowledge encompassing decades, all effortlessly incorporated into the novels. On Robinson’s website, readers can access “playlists” from several of the novels. Additionally, several of the titles in the series are from well-known songs: Piece of My Heart, Many Rivers to Cross, Bad Boy, Friend of the Devil.

“Music was always a big part of Peter’s life,” acknowledges Halladay. “He was lucky to have been a student at the University of Leeds during the heady 70s and saw popular groups like The Kinks, The Rolling Stones, Paul McCartney and Wings, as well as more traditional music like Lindisfarne and Fairport Convention. He would brag about actually being at the original Who, Live at Leeds concert at the Refectory of the University in 1970.

“He always felt that the music was an integral part of his books and enhanced the atmosphere. Many people told him that his playlists were remarkable, and they were often introduced to new artist merely by reading his books. Even though he included a lot of musical references in the books he was very casual about it.

A few days before Peter died, I heard music playing when I went into his into his room in the ICU. When I asked him what it was he said ‘Chopin. My nurse is Polish and I want to get on her good side.’ He always kept his sense of humour.”

His greatest love was probably The Grateful Dead. During the pandemic he discovered a number of their concerts were available on YouTube and I would often find him listening in awe to Jerry Garcia riffs. What a long strange trip it’s been…”