“Der Nachtmahr” by Henry Fuseli, 1790/1791. Rooted in Norse mythology but tenacious in European folklore, nachtmahre are creatures that possess people as they sleep, causing anxiety, panic, and bad dreams. The term is the etymological root of the English word “nightmare.” Otherworldly beings attacking a person’s sanity and testing their faith are an archetypal motif of Dark Romanticism.

“Der Nachtmahr” by Henry Fuseli, 1790/1791. Rooted in Norse mythology but tenacious in European folklore, nachtmahre are creatures that possess people as they sleep, causing anxiety, panic, and bad dreams. The term is the etymological root of the English word “nightmare.” Otherworldly beings attacking a person’s sanity and testing their faith are an archetypal motif of Dark Romanticism.

From song titles to BDSM dating apps to erotica with sexy and dangerous billionaires waiting to be tamed,it is safe to say the term “dark romance” has changed meaning since its inception. In fact, few literary movements are probably as ambiguous, obscure, and even misunderstood as Dark Romanticism, Romanticism’s black mirror. It is curious, especially considering how influential it once was and how universal its telltale themes and motifs still are in Gothic and horror literature today. This essay attempts to demystify Dark Romanticism, shed some light on its roots and its influence on literature, and hopefully, illustrate why it remains one of the most fascinating literary movements to this day.

There are two main reasons why Dark Romanticism is obscure. First, it is an elusive term. In its broadest sense, Dark Romanticism could be considered a subgenre, but that definition is shaky. Except for perhaps the works of E.T.A. Hoffmann, few writers and their works were consistently Dark Romantic, though many share its unmistakable themes up to this day. In his 2007 dissertation on the subject, German literary scholar André Vieregge defines it as a thematic structure, an amalgam of specific themes and recurring motifs applicable to any genre. The second reason is the stigma surrounding much of speculative fiction in (mainly European) literary academia, where fantastical elements are often frowned upon or seen as pulpy. Considering the popularity of speculative fiction and how many of literature’s greatest works contain fantastical elements, this is not only an elitist but also unreasonable sentiment: instead of dismissing these elements as immature, we should analyze the psychology and reasons behind them, as I will try in the following paragraphs.

It is hard to define a starting and ending point of Dark Romanticism, but it is generally agreed upon that it began in the second half of the 18th century, with English works such as Horace Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto (1764) or William Beckford’s Vathek (1786), peaked across Europe in the early 1800s, and faded with German writer Eichendorff’s death in 1854. Even though the first Dark Romantic works were by English writers, it is hard to confine it to a specific country. With the early 1800s being an age of relative peace, the upper class’s travel and cultural exchange was common and allowed Romanticism and Dark Romanticism to disseminate across most of Europe and America.

To understand what defines Dark Romanticism, it is helpful to look at Romanticism more broadly and the era that preceded it, the Age of Enlightenment, the philosophical and intellectual movement that dominated most of the 17th and the mid-18th century. In an unprecedented wave of clarity, it swept across Europe, spreading values such as rationality, secularism, and the evidence of the senses, the idea that the perceptible should be the lodestar of thinking. Significant scientific advances followed, with inventions such as the steam engine laying the foundation for the Industrial Revolution; it was an era that put reason first and foremost and can be considered the basis of modern liberalism.

If all that does not sound particularly romantic to you, then it is because it is not. In many ways, Romanticism’s values appear to be in stark contrast to those of the preceding era, focusing on themes such as the sacred beauty of nature, solitude over bustling cities, and a fascination with faith and the supernatural. To call it a countermovement is only partially accurate: rather than reject Enlightenment values, Romantics sought to marry those newfound values and ideals to the single most significant characteristic of Romanticism: the search for transcendence. Knowing this, it is probably easy to understand how the term “romantic” earned its present-day meaning: romance is irrational, emotional, and, at least at its ideal, transcendent.

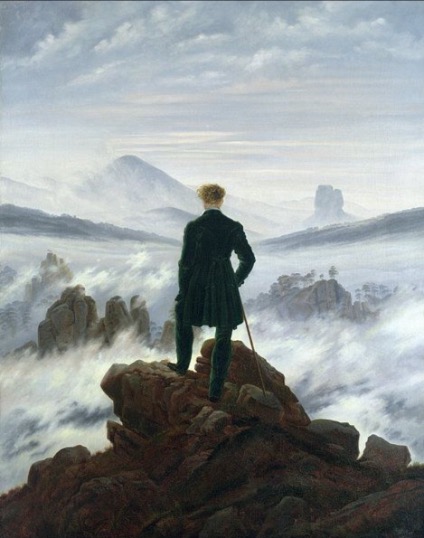

“Der Wanderer über dem Nebelmeer“ (The Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog, 1818) by German Romantic painter Caspar David Friedrich is among the most famous paintings of the era. It encapsulates many Romantic ideals: solitude, the beauty of nature, and the quest for transcendence.

“Der Wanderer über dem Nebelmeer“ (The Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog, 1818) by German Romantic painter Caspar David Friedrich is among the most famous paintings of the era. It encapsulates many Romantic ideals: solitude, the beauty of nature, and the quest for transcendence.

So, where does Dark Romanticism fit into all this? Simple: it is the flipside. While sharing a lot with its hopeful cousin—transcendence, loneliness, and nature are core themes of both movements—Dark Romanticism focuses on the negative aspects of transcendence, the, as German literary scholar Gero von Wilpert puts it, Nachtseiten (night sides) of the human condition. Romanticism explores the world’s and the mind’s potential for the sublime; Dark Romanticism explores their most frightening depths.

There are dozens of Dark Romantic motifs, but according to Vieregge, the most emblematic are the unexplained supernatural, the horror in technology, and the supernatural as a trial of character.

The unexplained supernatural contrasts the explained supernatural of Gothic novels such as Ann Radcliffe’s, where seemingly paranormal occurrences end up having a perfectly rational explanation. It goes like this: in a realistic world—meaning a world that is or very closely resembles reality—an inexplicable element invades a protagonist’s life. Upon realizing they are facing with the undeniably supernatural, the protagonist must question all they know and find a way to integrate this element into their reasonable worldview, thereby proving the existence of a transcendental plane of existence. The short story Dr. Heidegger’s Experiment by Nathaniel Hawthorne (1837) provides an excellent example of this motif: confronted with a vase of water that miraculously reverses age, it presents undeniable proof of the transcendental plane. Equipped with this knowledge, the story ends with the three guests setting out to find the water source.

The horror in technology is self-explanatory. As fascinating as the Enlightenment’s many technological developments were, their implications were equally daunting. Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818), where scientist Viktor Frankenstein builds a creature in his laboratory that develops consciousness, is the archetypal example of this confrontation with technology’s ethical implications. Shelley expertly uses the supernatural to explore the boundaries of science, the godlike powers it bestows upon humanity, and what it means to be human. Another excellent example of this motif is E.T.A. Hoffmann’s Der Sandmann (The Sandman, 1816), where a man falls in love with a woman named Olimpia, who turns out to be an automaton. If something seems and acts human, is it human? It is a fascinating exploration of scientific ethics.

Olimpia from E.T.A. Hoffmann’s “Der Sandmann” (1816). Like Edgar Allen Poe in English literature, Hoffmann is considered the seminal German Dark

Olimpia from E.T.A. Hoffmann’s “Der Sandmann” (1816). Like Edgar Allen Poe in English literature, Hoffmann is considered the seminal German Dark

However, the most significant and arguably the most intriguing motif of Dark Romanticism is the supernatural as a trial of character. With very few exceptions, the dangerous supernatural—vampires, ghosts, monsters—in Dark Romantic novels is never invincible. In fact, its purpose is almost always a test of a protagonist’s inner strength and soul (and often piety), where failure results in insanity and death and victory in a heightened understanding of oneself and the world. This aspect also sets Dark Romanticism apart from early horror literature, where the supernatural was always an external threat destined for defeat. Hoffman’s novel The Devil’s Elixirs (1815) is emblematic of this motif: in the story, a monk, entrusted with the safeguarding of a “devil’s elixir,” gives in to his temptation to drink it, setting events into motion which end in his downfall. The supernatural tested his character—and he failed. As gruesome and pernicious the horrors in Dark Romantic may be, they are never omnipotent and could, in theory, be bested by virtue and strength of character—and while the protagonists often fail, the choice was always ultimately in their hands. H.P. Lovecraft was the first author to break with this convention, introducing a new kind of omnipotent, supernatural evil before humanity is utterly powerless.

Seeing these three motifs put together, it becomes evident that Dark Romantic motifs are all but dead in modern literature—the fascination and even yearning of the darkly transcendent; the horror in science; the supernatural as a test of a person’s character. Almost all of Stephen King’s works could qualify as Dark Romantic: in Christine (1983), an animate piece of technology drives its owner Arnie Cunningham into social isolation. In IT (1986), an ancient, malicious deity that feeds on fear and—careful, spoiler incoming!—is ultimately vanquished by the friendship of the Loser’s Club. In Revival (2014), a scientist uses mystical dark electricity to bring people back from the dead. Even Netflix’s latest Egyptian mystery show Paranormal (2020) revolves around a scientist trying to rationally explain the paranormal experiences he keeps having—a setup that could not be more Dark Romantic if it tried. For all its obscurity and ambiguity, Dark Romanticism has left an undeniable mark in speculative fiction. And why wouldn’t it? There is a magnetic fascination with the darkly transcendent; even if the reasonable part of our minds tells us its nonsense, there will always be that quiet voice that tells us there is more than meets the eye. To quote Marie Du Deffand, a French patron of the arts and friend to Horace Walpole: “Non, je ne crois pas aux fantômes. Mais j’en ai peur.”

“No, I don’t believe in ghosts. But I fear them.”

A big thanks to André Vieregge, whose counsel and dissertation Nachtseiten: die Literatur der schwarzen Romantik made this essay possible.

***