At the beginning of my new novel The Hollow Tree, a man stands on the roof of a Scottish hotel. It is night, and the distant mountains are hidden. It is rural Argyll, and the stars above are clear in their spiralling array. The nearby sea murmurs, but in the dark it is invisible. The man is naked, and his toes grip the stony edge of the battlements of the baronial tower. Behind him is safety. Before him is a sheer drop into darkness.

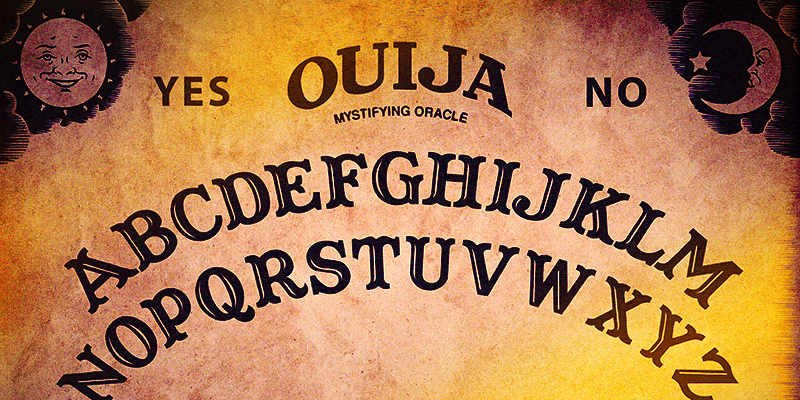

He is not alone. He turns around to face Shona Sandison, a journalist, who is staying at the hotel for a wedding. To her surprise, she can see his chest is adorned with a complex tattoo. But it is not a picture or decoration on his exposed flesh; instead, there are the letters of the alphabet and the numbers 0 to 9. On his right shoulder is Yes, and on his left shoulder, No. It is a depiction of a Ouija board. He speaks to her, intoning phrases she cannot understand or recognise. Then he throws himself from the roof, to his death.

So begins The Hollow Tree, my second novel with the investigative reporting of Shona at its heart. Determined to find out why the man—Daniel Merrygill, a school friend of the bride—killed himself in such a way, she pursues a series of clues, tips and remembrances to a small rural town in the north of England. It is here, in Ullathorne, where poor Daniel and a small group of friends once toyed with Ouija boards in the early 1990s. What they did there, and then, reverberates into the present.

I have long planned to write a book based around the curious, contested movements of the Ouija board. They hold an eerie fascination. I have noticed in others they elicit a shudder, or perhaps, at the least, a shivery curiosity. Maybe, even, a roll of the eyes. Personally, I have not touched one since I was also a teenager growing up in a remote rural town in the north of England.

But the Ouija board sessions were product of a deep boredom. If you were a teenager in the early 1990s, especially in a small rural northern town with no cinema or rapid links to a city, there wasn’t much to do. There was sport, of course, but I was a duffer. There was, mercifully, alcohol, and the odd sniff of drugs. There was no internet, no mobile phones, and no multi-channel TVs. There was no music to download. There were books, of course, but no YouTube. You could buy CDs, but I was skint. New music, desperately read about in Melody Maker and New Musical Express, had to largely be imagined, apart from one or two late night shows on Radio 1. So, as in my own experience, Dan and his friends, on the painful edge of leaving school, on that painful edge of impending adulthood, turn inwards and, perhaps, downwards.

A board is easy to set up. All you need to do is write. There is not a grand magical ceremony—no need for obscure substances or candles. No need to draw a pentagram or wait for the right phase of the moon. And so it was for us. Of course, the movement of the glass over the letters triggered questions all such users of the board have asked. Are we moving this? If I am not, who amongst my group is? Is this real? Why does the glass move so fast? Is someone trying to say something? What is trying to say something?

Again, in my case, the movements spelled both gibberish, and disconnected, disordered, words. When a word or a fragment of a message was spelled out, it was unnerving. We held our breaths. Our voices became heightened or inaudible. It became addictive. What was happening? I figured enough was happening. I vowed, after a time, not to touch them again. Perhaps my long hours I had spent in the church in my youth had its effect. Perhaps that was a blessing.

After all, the messages are assumed to be coming from the dead, from the afterlife. What if the board is “working” but cannot contact the dead? Then who was contacting us?

Ouija boards and their use exist at the edges of conventional society. They have been damned, condemned, celebrated, and featured in movies. They were even advertised, back in the day, as a fun thing to do on a date. Artists and writers have been fascinated by them, and even consulted them. WB Yeats, no stranger to the eldritch and arcane, used them, and so, of course, did Crowley. Regan’s Captain Howdy was summoned with a board. The poet James Merrill’s long Ouija-inspired poem The Changing Light at Sandover (1982) won major prizes.

Their history is a little murky, appropriately. They appear to have come from the US, emerging after the massive death toll and social disruption of the Civil War. Spiritualism tends to rise after large traumas, and interest in the afterlife later rose again after the First World War. The name for the talking-board was apparently coined by Helen Peters, a medium who was using the board with her brother-in-law Elijah Bond one night 1890 in Baltimore.

More interesting to me was the story was the fate of William Fuld, the American entrepreneur who marketed the board, especially in national catalogues like Sears. I first read about him in an edition of the Fortean Times, but his story can also be read here, in this article in The Guardian. To summarise: the board told him to expect a heady expansion in business. Then, one day, he was supervising the replacement of a flag pole on top of his Baltimore factory. He fell. As The Guardian relays: “He broke several ribs, but was expected to survive, until a bump in the road on the way to the hospital sent one of the fractured bones through his heart and he died.”

Ouija boards are a fascinating tool for a mystery novel. Besides the issue of whether the messages are real or not, there is the core of their appeal: words. Phrases. Sense or nonsense. Do they mean anything or not? Are there multiple meanings? Everyone around a board can sense or understand the words differently.

In The Hollow Tree, a group of friends in the 1990s receives messages on a Ouija Board. The messages, spelling out by a glass over letters and numbers, are the same and repeated endlessly. Each member of that group takes the messages to heart. And all in different and personal ways. Thirty years later, it leads to the terrible tragedy at the hotel, and, through the investigations of the journalist Shona Sandison, a path is beaten back to the past.

Whether the messages on a Oujia board are “real” or not is not really the main question in The Hollow Tree. It is the power of the words they appear to generate which is the nub. In The Hollow Tree, these words, these messages, these gnomic utterances, have the power to change and direct lives.

And beyond that, in The Hollow Tree, underlaying it like a black cloth, there is the question of time, and of where our personal deaths are within time.

Some see time as a line, stretching back from the path to the present and then on, to the future. Others have said time is a circle. Maybe it is both: a line that circles, like a spiral. Like the DNA within us. Or all the galaxies beyond us. This is a spiral we are all climbing—and maybe, sometimes, we get a peek of the levels above and below. And maybe the people there can see us and contact us in the only way they know how: through words.

Or: maybe—and this is an idea I also pursue and investigate in The Hollow Tree—time is more like the course of flowing water. You, me, we, are living in its cycle. Moving always from the deep churn of the water in the sea, to the moving landscapes of the clouds, down to the high streams and becks, falling into the beautiful rivers, and back to the roiling sea.

And, again, if you survive death in some way, you are freed from this cycle. So, you can sit or stand or lie on the banks of the course of time. You can see its entire course. Maybe you can move along it and see time future, or time past, or time present, whenever you want. Maybe you can temporarily dive into the water of time, and see the living, speak to them, and then leave again. And if someone calls to you, you can answer. But what else is there, along the path of the water? Is it just the dead of humanity? What else could there be, apart from our dead? Maybe it is safer to never find out.

***