There’s a joke among millennials that our favorite childhood television shows would have sucked if the characters had owned smartphones. Videos of Buffy fighting vampires would have been uploaded to TikTok in a second; Joey would have spent her evenings texting Dawson instead of sneaking through his window; and Mulder and Scully could have tracked each other’s locations via an app. Even now, many screenwriters making media for young adults ignore smartphones or use them sparingly, perhaps because they feel that too many small screens on a big screen either detracts from the cultivated aesthetics of their show (a la Chilling Adventures of Sabrina and Wednesday) or quickly becomes boring. It’s also possible they find it disheartening to incorporate the technology that has led to such negative impacts on their target age group, including a decline in mental health, sleep disturbances caused by excessive blue light, and the theft of private information by companies who already steal teens’ time with “innovations” like infinite scroll and autoplay.

Like other writers, authors of young adult novels have had to cope with the ubiquitousness of smartphones. Visually, we have it easier than screenwriters because we’re already working in a text medium, so messages, social media posts, and emails can be more seamlessly integrated onto the page. But the fact of phones still haunts our plots, especially those of us who write mysteries and thrillers, where too-quick communication or immediate access to the internet can prevent necessary misunderstandings, suck the suspense out of clue-gathering, and give teens playing detective an anticlimactic way to get help if their investigations get them lost or injured.

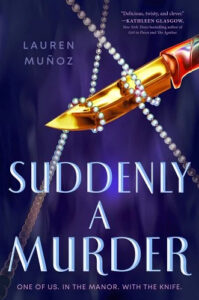

There are two ways YA mystery writers usually handle the smartphone conundrum: avoid or embrace. I’m a fan of the first one because it makes plots more likely to resemble the Golden Age detective fiction I love (those books would also have been ruined by phones; imagine Miss Marple reverse image searching Major Palgrave’s picture of Tim Kendal in A Caribbean Mystery and figuring out his secret identity within an hour). Many Golden Age novels, in order to create a closed circle of suspects, are set in isolated locations: sprawling country homes, lonely islands, trains trapped in snow, etc. Similarly, putting teens somewhere remote is the fastest way to take the internet out of their hands. Gretchen McNeil and I chose islands battered by storms (Ten/Suddenly a Murder). Maureen Johnson’s characters attend boarding school high in the mountains (Truly Devious). Diana Urban’s latest is set on a cruise ship (Lying in the Deep).

YA mystery authors are comfortable contorting our plots around reality because we have to make the logistics of teens solving murders believable. Believability is a complicated issue that deserves its own discussion, but while I think the concept underestimates the potential of teenagers, who are often significantly more capable of independence than our society gives them credit for, publishers and readers want contemporary mysteries to feel grounded in the same perceived reality of what teens are like that’s been codified into popular culture by (mostly middle class and white) writers over the past few decades, and so we shift the circumstances of our teens’ lives to give plausible reasons for them to behave outside the norm. We write parents who are neglectful, nightshift workers, or, in classic Disney fashion, dead. Our teachers are more oblivious and permissive than in real life, while our police are less arrest-hungry. And we explain away why teens are investigating murders in the first place (cold cases left unsolved, cops not doing their jobs, money for college).

Although I prefer the more organic interactions of a smartphoneless world, I’m intrigued by the possible benefits of embracing smartphones in young adult mysteries. Beyond the increased relatability for teens, all of the plot problems I mentioned above as drawbacks can also be used to enrich the story. Quick communication can prevent the solution from hanging on the thread of a simple misunderstanding, an often unsatisfying conclusion for readers; access to the internet means our clues can be more elaborate and inventive because teens can retrieve expert knowledge with a few swipes of their thumbs; and contacting others in life-or-death situations can be written in a way that heightens tension, as when friends come to the detective’s rescue.

Including smartphones in YA mysteries also allows authors to address some of their more nefarious applications. Anyone who has listened to a true crime podcast like Serial knows how often suspects’ phones are used in police investigations. Location tracking, search history, data pulls that reveal both the substance of our communications and the moment we open an app—our phones record minute pieces of information the government can use to recreate our movements and dig into our lives. But teens, especially those who have been raised on screens, might not understand the consequences of keeping a computer in their pockets. Sure, they’ve been told their phone tracks them (often along with their parents), but it’s hard for even adults to process the magnitude of how much private information we share with corporations and, because of the government’s ability to subpoena records, with police departments and the FBI.

When I was in law school, I took a class called Race, Biotechnology, and Law in the Gene Age with Dorothy Roberts, an expert in policing. One thing I learned that has obsessed me for years is that the government uses open genealogy databases to conduct warrantless searches on people who have never been arrested or convicted of a crime. Because DNA contains information about our extended family tree, anyone who hands over their DNA to ancestry sites is passing on the private genetic information of generations of family members who have not consented to being catalogued or tracked. In a parallel exploitation of our personal information, corporations use the data collected from phones to surveil consumers so they can manipulate our buying behavior and that of the people around us. They also sometimes give the profiles they build based on our internet activity to advertisers, politicians, and the police. As many adults don’t know the extent of these intrusions, it’s unlikely most teens are aware of the ways their private information can and will be used against them.

Since learning that my debut was going to be published, I’ve been thinking a lot about the influence young adult authors have on teenagers. Before I was a lawyer, I was a public school teacher, and while I dislike the line of thinking which says that young adult books should be educational, I also know that even fiction that’s not intended to inform still can (thank you, Judy Blume!). YA mystery writers have the opportunity not just to add smartphones for authenticity but to craft our crimes in ways that illustrate how technology is used (and misused) by the police. I hope that teens who see our characters tangle with the thorny twin problems of government and corporate abuse will grow up to care about digital privacy—and maybe even be inspired to advocate for laws that will protect us all.

***