I was offered moonshine for the first time in my freshman year of college. I went to a small school in southwest Virginia, not far from Franklin County, popularly known as the Moonshine Capital of the World. A friend of mine was seeing a boy from Franklin County, and one night he brought us moonshine in a Gatorade bottle. Someone mixed it into screwdrivers and we drank it on the hill behind the tennis courts. I never saw that guy again, but the taste stayed with me, a burn at the back of the throat.

Where I grew up, being offered moonshine at a party didn’t seem much more unusual than being offered weed, and it wasn’t until I moved away for graduate school that I realized that most of the rest of the country associated it with Prohibition in the 1930s. When the sale of alcohol was prohibited in the United States between 1920 and 1933, an entire industry sprung around the manufacture and sale of illegal liquor. Everyone knows about speakeasies, bootleggers, and Al Capone, but very few people I met seemed to realize that when the rest of the country stopped making and drinking moonshine, Appalachia kept right on.

That was probably just how the Appalachians wanted it. They’re a fiercely independent bunch, and the less the outside world knew about what they were doing, the better. Moonshiners made their product and either sold it locally or transported it to bars in big cities known as nip joints, where it could be sold under the counter for much less than the cost of legal taxed liquor. It may have seemed like the government was turning a blind eye until the 1990s, when a series of federal raids virtually shut down the moonshine industry in Franklin County.

I graduated from college in 2000, and after fifteen years away from Virginia, I moved back to a small town in the same part of the state and started hearing about moonshine again. When friends heard that I was writing a book about a moonshining family, people came out of the woodwork. One friend, a teacher with a Ph.D. in history, told me that her grandfather had been a bootlegger. My hairdresser said she always kept a jar in the freezer in case of illness. Another friend offered me a taste one night when we were talking in his back yard. He gets it from a family member, who gets it from a guy whose name my friend has never heard. It may not be everywhere, but it’s around if you know who to ask.

I knew this is something I wanted to write about, so I tried to read everything I could find about moonshining. I found plenty of articles online, but given the many amazingly talented Appalachian writers out there, I was surprised at how few novels I could find about this topic. Elmore Leonard’s The Moonshine Wars and Matt Bondurant’s The Wettest County in the World (which was adapted into the movie Lawless) focus on moonshiners and bootleggers, but they’re both set in the past. (There is a reality show on the Discovery Channel called Moonshiners, but I haven’t been able to bring myself to watch it.) I wanted to read something about real, genuine, modern-day moonshiners, and if that book didn’t exist, I’d have to write it myself.

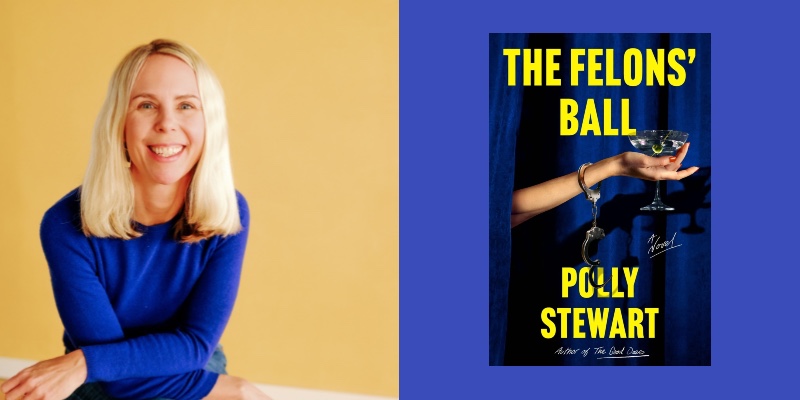

In my new novel, The Felons’ Ball, Trey Macready and his brother Leo have established a successful contracting business and left their moonshining past behind—or at least that’s what Trey’s daughter Natalie thinks. Then, on the night of their family’s lavish annual party known as the Felons’ Ball, Natalie’s secret boyfriend, Ben Marsh, is found murdered. Ben was also Trey’s best friend, and in the wake of his death, Natalie has to figure out if her family has truly left the past behind.

I loved writing this novel because it gave me a chance to research a history and culture that fascinates me, but also because I could focus on the lives of the women who tend to stay in the periphery of these kinds of stories. Trey Macready is a man who feels entitled to do whatever he wants, and Natalie is just discovering how the women in his life may have been drawn into complicity with his actions without even knowing it. Things get even more complicated when she gets involved with the local sheriff, who may or may not be willing to look the other way when it comes to the Macreadys’ family business.

Certainly, at this point in history, we’re all aware of the destructive potential of men who feel entitled to break the law with impunity. I don’t think most people feel a lot of sympathy for these men’s wives and daughters, and I don’t either, but I do want to understand them. I wanted to write about the line where ignorance ends and complicity begins, and I wanted to explore it through a character like Natalie, who has to make a decision about whether or not to step over that line.

Although I started with a culture that’s mostly confined to my little section of the U.S., I think these questions are accessible to anyone who’s interested in crime and accountability. The Macreadys may buy corn and sugar in bulk, but under the surface, they’re just like other rich and privileged families who think they can get away with anything—up to and, maybe, including murder.

***