The 1977 Creation Convention was a transitional event in terms of my comic book worldview. It was where I was introduced to the amazing work of Jim Steranko and George Perez, first saw the exquisite paintings of Jeff Jones and Barry Windsor-Smith, and met friendly newcomer/Joe Kubert School undergraduate Steve Bissette, who’d later go on to illustrate Swamp Thing. Held in New York City over Thanksgiving weekend, that first afternoon I befriended a chubby kid (we were both 14) who was an Art & Design High School freshman as well as a convention regular. When we about to walk through the doors that connected Artists Alley to the main showroom, I noticed a very cool looking man sitting in the lotus position on top of a table puffing a cigarette while merrily doing a Batman sketch for a fan.

Dressed stylishly, he had an aura of cool and a pack of True Green nearby. In those days many folks smoked, some more than others. Impressed, I stared at the dude, who looked up from the drawing pad, exhaled a cloud of smoke and smiled. “Who is that?” I asked my new friend. Glancing back, the kid replied, “That’s Marshall Rogers.” I must’ve looked puzzled. “He’s the latest Batman artist.”

Since I’d stopped reading superhero comics a few years before, concentrating on horror and science fiction books, I’d never heard of Rogers or seen his work. That afternoon I found the first four Detective Comics that featured Batman stories illustrated by Rogers. Days later, when I finally dived in, I was quickly lured into Rogers’ work, art that had a cinematic feel that was as dark and alluring as an old school noir. Often a beginner’s work stylistically resembled more established artists, but Rogers’ pages were completely his own. Though Detective was his first regular book, Rogers came to Batman fully-formed as an artist with a style of his own.

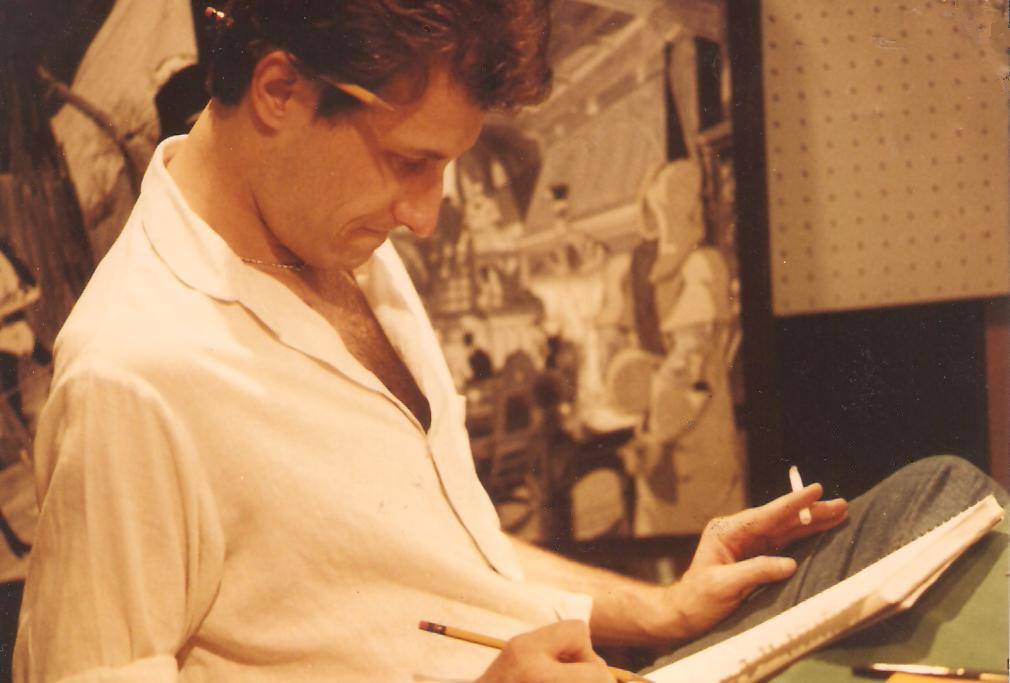

Rogers, photographed by Tom Oberlin, circa 1980s.

Rogers, photographed by Tom Oberlin, circa 1980s.

“Marshall Rogers’s clean, elegant not overly-muscled style of anatomy was a welcome departure from how superheroes were drawn in that day, Batman no exception,” says crime novelist/ comic book writer Gary Phillips. “You could take in a Rogers’ composed page, particularly as inked by Terry Austin, and appreciate the dynamic composition, the narrative flow that worked together as a whole.”

For the next decade Rogers’ distinctive style laced other books I read and loved including Mister Miracle, Doctor Strange and the groundbreaking graphic novel Detectives Inc.: A Remembrance of Threatening Green, a pulp fiction project written by Don McGregor and published by Eclipse Comics.

In our post-Sin City/100 Bullets/Stray Bullets world, crime comics are part of the mainstream, but more than four decades before McGregor and Rogers were pioneers in the graphic noir department. Detectives Inc. was the story of a salt-n-pepper duo of New York City private eyes hired by a lesbian midwife to find out who murdered her lover. McGregor has said that Ted Denning, the white guy, and Bob Rainier were originally inspired by the Robert Culp and Bill Cosby characters on the sixties series I Spy, though, as Phillips pointed out, they were more like that same acting duo playing two down on their heels Los Angeles private investigators in the gritty film Hickey & Boggs. In A Remembrance of Threatening Green there were also traces of the stark cop series N.Y.P.D. with Robert Hooks and Frank Converse, 1970s cinema ranging from Taxi Driver to An Unmarried Woman, and the fictions of Ed McBain, Richard Price and Ernest Tidyman.

McGregor had worked on the characters through various scripts since 1969 when he lived in his hometown of Providence, Rhode Island, collaborating with future Blackjack creator Alex Simmons. According to a May 2020 interview, he’d initially created Denning and Rainier for a screenplay (Death Game of Three Dimension) for him and Alex to play in a self-directed film. Later, he transformed the material into a short story.

“I was taking that to places like Mike Shayne, Mystery Magazine,” McGregor told Comic Book Historians, “but then I said to Alex, ‘Hey, why don’t we do our own comic book…We’re going to Phil Seuling’s thing (convention) next year, why don’t we do our own comic?’ And that became the first Detectives Inc.” That self-published comic “All That Is Left Is Anger” was instrumental in getting McGregor work at the horror comics company Warren Publishing.

McGregor’s first published short was “A Tangible Hatred,” illustrated by Richard Corben, in 1971. “The hallmarks of McGregor’s style are all there,” reported the website Diversions of the Groovy Kind. “The unique plot, the verbose scripting, the humanity, the challenge.” Still, McGregor never gave up on selling some version of Detectives Inc., writing a second script for Simmons titled “They All Died.” Artist Neal Adams offered to help ink the pages, but that never happened, because Simmons decided to concentrate on acting instead of finishing the project.

Adams, a leading art star at Marvel and DC, was also supportive of a few of the independents that were beginning to rise in the 1970s. “There was a point in comics where the form itself began to innovate within the alternative publishers like Star*Reach, First Comics, Comico, Sal Q. and Eclipse Comics,” recalled graphic novelist Tim Fielder. The auteur behind Infinitum: an Afrofuturist Tale, he cites Rogers as an early influence. “Within that era artists and writers like Rogers and McGregor, both who were well established in superhero work, began to push the boundaries of both subject and storytelling.”

In 1968 Neal Adams rose to prominence as the artist behind Batman, which was written by Denny O’Neil. Drawn in a neo-realistic style that was dynamic and dramatic, Adams brought back the Bat’s “dark knight” persona after years of campiness that streamed from the goofy, but popular TV show. Adams’ time drawing Batman, Brave and Bold and Detective was instantly legendary. In addition to his own work, he was also instrumental in helping many emerging talents including Alan Weiss, Mike Nasser, Josef Rubinstein, Rick J. Bryant, Terry Austin and many others.

Those young artists hung-out and worked at his studio Continuity Associates. Located on the third-floor of 9 East 48th Street, it was a space where they worked in various artistic disciplines that included book covers, advertising storyboards and movie posters in addition to their comic book assignments. Originally co-owned with fellow artist Dick Giordano, Continuity, on any given day the offices were under siege from novice artists milling around hoping to show Adams their portfolios, praying that he’d help launch their career.

Though he could be supportive, Adams was also brutally honest. If an artist was straddling in the amateur zone, he told them the truth. For every Bill Sienkiewicz, who he sent directly to Marvel, there were those he didn’t believe were worthy. The first time Marshall Rogers presented his work to Adams, the master dismissed him. “He told me to give up and get a real job,” Rogers told Comic Book Artist magazine in 2002. “I do remember it being like a challenge that I had to prove that I could do it.”

***

Born In Queens, New York on January 22, 1950, Rogers was raised in Ardsley, a town in Westchester County. While he read comics at an early age, starting with the Walt Disney books, he later moved on Wonder Woman and Batman. A few years later he discovered Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko at Marvel, which put him on the drawing path. In later years he’d cite Howard Chaykin and Walter Simonson, especially the latter’s work on Manhunter, as inspirations. However, instead of pursuing a comic’s career straight out of high school, Rogers enrolled at Kent State University as an architectural student.

Still, after realizing that the world wasn’t yearning for another Frank Lloyd Wright, he left school in 1971 and moved to New York City to pursue a commercial art and comic book career. Taking on illustration assignments from low-level men’s magazines and drawing a comic strip for the first issue of Cheri, Rogers paid his starving artist dues for a few years. He began breaking into the field in January, 1977 at Marvel Comics where he did illustrations for the company’s British editions under the supervision of Marie Severin.

Artist Lance Tooks, who was an assistant to Severin, remembers Rogers as a nice guy with an infectious smile. “He had an identical smile as the Joker,” Tooks recalled. After Rogers drew two Daughters of the Dragon strips from Chris Clarmont scripts for The Deadly Hands of Kung-Fu for Marvel, he brought his work to DC Comics art director Vince Colletta. At DC, he was assigned what was supposed to be a back-up strip in Kamandi that later became the Weird War story “A Canterbury Tail,” inked by fellow newcomer Terry Austin. It was Neal Adams who suggested Rogers team-up with Austin, who’d been working with him and Giordano.

“I was impressed right from the start,” Austin told Comic Zone Radio in a 2007 interview. “Rogers pulled out all stops to make the work unique.” Both artists worked out of Continuity, and the art they delivered was energetic, wild and powerful. The script was silly, but the images were stunning. That 12-page assignment led to Rogers drawing the bonkers Batman tale “Battle of the Thinking Machines.” Scripted by Bob Rozakis for Detective Comics #468, the story was supposed to be drawn by veteran artist Jim Aparo, but he became ill.

However a couple of editorial higher-ups weren’t pleased with Rogers’ fresh style and, according to Austin, cursed the penciller out, told him he couldn’t draw and called him an idiot. Austin told in The Batman Companion, “We took a lot of abuse, because we were both doing things that didn’t look like other people’s work. Joe Orlando would loudly inform us how worthless we were.”

Those same haters were surprised when fans wrote letters praising Rogers and Austin’s work and asking for more. Though Walt Simonson was brought in for Detective Comics #469 and #470, both written by Steve Englehart, Rogers returned to book with #471. Englehart stayed on as writer, but neither he, Rogers or Austin could’ve predicted that their six-issue Batman run would become one of the renowned storylines of the era and, forty-five years later still, inspires.

The trio’s work was a brilliant blend of noir, romanticism, comedy and drama. Years later, Rogers would make a point to tell interviewers that it was a team effort that made those books special. As preparation, Steve Englehart read back issues of Detective Comics from the ‘30s and ‘40s, deciding that Batman should be more adventure hero than super. “I always knew that Batman had come from a pulp background,” he said in 2007, “and was connected to the Shadow and the Spider.”

Building on the O’Neil/Adams model, but taking the darkness aspect one step beyond, Englehart wrote full scripts in advance of the art team being chosen and jetted off to Europe to write his debut novel The Point Man (1981). He’d never met Rogers or Austin before leaving town, but seeing their work when he was in Spain made him happy. Rogers, using his skills as a trained architect, brought Gotham alive as a character as Batman climbed down chimneys, ran across rooftops and hunted villains on rain slicked streets.

In 1979 an uncredited writer noted in a bio one-sheet, “Marshall’s architectural training served him in good stead while illustrating those stories. His detailed renderings of the cityscapes of Gotham City reflected much greater time and care than the usual comic book backgrounds.” In 2007 Englehart said, “I was astonished by the work they were doing. Layouts, storytelling, it was all perfect.” In addition, Rogers made Batman’s costume more sinister, one that seemingly had a menacing life of its own.

Over those six issues, the Dark Knight dealt with political villain Rupert Thorne, successful businesswoman girlfriend Silver St. Cloud, psychotic nemesis Joker and the revengeful ghost of Hugo Strange. “Rogers and Englehart’s Batman was the foundation that Frank Miller (The Dark Knight Returns, 1989) built on,” Tim Fielder said. “Sometimes it sucks for the creator and the audience being too far ahead of the wave.”

Decades later, CBR.com placed the Englehart/Rogers six-issue run, known by some as Strange Apparitions, as one of the ten Batman story arcs every fan should read. “It was also one of the most fruitful Batman runs of all time,” David Harth wrote in 2020. “The stories the two worked on would serve as inspirations for the first Batman movie in 1989 and for some of the most beloved episodes of Batman: The Animated Series. The two creator’s stories stand the test of time, serving to modernize the Dark Knight.”

Rogers also drew brilliant Detective covers, my preference being the bugged-out “The Laughing Fish” (#475) and spooky “The Sign of the Joker” (#476), which featured an obviously crazy Batman with Joker grin and three corpses under his cape. It was through drawing the covers that Rogers refined his skills as an illustrator, an ability that came in handy the following year when he was recruited to provide the graphics for the Batman prose story “Death Strikes at Midnight and Three” by Denny O’Neil.

Published in Batman Spectacular (aka DC Special Series #15/Summer, 1978), the short story allowed O’Neil to channel his inner Cornell Woolrich as Batman searched through the nighttime Gotham (at its most New York City) for hired killers and a crazy crime boss. Racing against the big clock, Batman must find the hitmen before they pull the trigger at 12:03. O’Neil, a genius comic book writer who had written short fiction for Fantasy & Science Fiction and Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine, and later penned a few Batman novels, delivered a satisfying story, but it was Marshall’s illustrations that stole the show.

There was a haunting, creepiness to his depictions of the characters that was noirish with a touch Ashcan School quality. The image of Batman hovering over Times Square remains one of the most memorable images of the hero from that era. “His stuff literally reeks with pulp drama,” Terry Austin said in 1979. “The grime of shadowed alleyways, the smell of the streets after a thunderstorm on a hot summer night, the haze of the skyline seen through a slowly drifting fog, the garishness of neon reflected endlessly in puddles of oily water.”

While Marshall Rogers would go on to draw many other characters, he revisited Batman often, even drawing a regular newspaper strip of the character in 1989 written by Max Allan Collins. “I appreciate that I got the opportunity to work on one of my first and favorite superheroes,” Rogers said in 1989. “I’m a dark child; I like dark, moody places. That is what Batman is all about. His whole essence works into one single purpose—to instill fear in criminals.”

***

Like many of his contemporaries in the 1970s and ‘80s, Rogers had no desire to stay on any book for years, and was openly experimenting with projects outside the corporate walls of the Big Two. Comic book artists Barry Windsor-Smith, Bernie Wrightson, Howard Chaykin, Frank Brunner and others began producing posters and collectable art portfolios. In 1979 Rogers illustrated Strange, a folio of six 11 1/2 x 16 black and white prints. Published by West Coast brothers Schanes and Schanes (who later changed the company name to Pacific Comics), the firm had already produced portfolios with Howard Chaykin (Robin Hood), Alex Nino (Dark Suns of Gruaga) and William Stout (Dragon Slayers). The first plate of the Strange portfolio was signed and numbered by Rogers, and was reproduced as limited edition of 1,200.

Strange also worked as a textless science fiction adventure story where the hero lived on some weird world in a gothic castle on top of a mountain. Rogers’ art had an off-kilter quality as though the world might turn upside down at any moment while Strange and his companions travelled by boat, horseback and space ship. Perhaps Rogers planned on taking his Strange creation further than a few illustrations, but, alas, that portfolio was the only appearance from the character.

Enclosed in the portfolio package was an “artist profile” that stated Rogers was completing a graphic novel, Detectives Inc., written by Don McGregor. Unlike today, back then the words “graphic novel” weren’t thrown around often and few knew what the hell it meant. American audiences were used to comics being geared towards the juvenile market, but the (then) new fangled graphic novels were determined to tackle more mature subject matter.

Writer McGregor, a former Marvel scribe who scripted Killraven, Black Panther and Luke Cage, had been evicted from “the House of Ideas” and was forced to branch out simply to survive. After years of ups and downs in the industry, he was finally writing the type of material that he’d long wanted to do. For many emerging alternative comics searching for an adult audience, it was simply about providing more nudity, not more mature content, but McGregor was smarter than that while also determined to bring Ted Denning and Bob Rainier back. Private detective crime tales were the subject of pioneering graphic novels including Gil Kane’s His Name Is…Savage (1968) and Jim Steranko’s Chandler: Red Tide (1976), and Detectives Inc. simply followed in that mean streets tradition.

“PI types in comics go back to Detective Comics before Batman showed up,” Gary Phillips said. Currently writing teleplays for Snowfall and editing Get Up Offa That Thing, an anthology of crime fiction inspired by James Brown songs for Down & Out Books, he is also a comic book aficionado. “McGregor and Rogers brought to Detectives, Inc. a gritty sensibility transplanted from what was happening in prose mystery and crime fiction in the 1970s be it Joseph Hanson’s gay insurance investigator Dave Brandstetter or Roger Simon’s weed smoking private eye Moses Wine. A Remembrance of Threatening Green sought to bring dimension to its main characters. The journey of self-discovery hinted at by Chandler and seeded by Ross Macdonald, had blossomed in ‘70s mystery novels and certainly was forefront in Detectives, Inc.”

Though McGregor’s work in both comics and prose could be overwrought and wordy, he was also a hell of a storyteller who layered his adventure stories with politics, sex, race and whatever else popped into his brilliant mind. “Despite or maybe because of his tendencies to be verbose and over-wrought, I nonetheless dug what McGregor was reaching for when he took over writing the Black Panther at Marvel,” Phillips said. Personally, I liked that McGregor wrote Black characters as though he knew a few Black people, might’ve even been their friend, and he had no interest in depicting stereotypes of any sort.

McGregor’s first indie project was his 1978 collection of short stories Dragonflame and Other Bedtime Nightmares. Published by Fictioneer Books, a company owned by late writer David Anthony Kraft, it was illustrated by Paul Gulacy. Next was Sabre, a black and white sci-fi fantasy with a Black hero that was the debut publication of new jacks Eclipse Comics. Owned by brothers Dean and Jan Mullaney, the company would soon become an alternative graphic art leader, publishing books by P. Craig Russell, Chris Ware, Jack Kirby, Jim Starlin, Alan Moore and Max Allan Collins’ female detective series Ms Tree.

Detectives Inc. retailed for $6.95 at a time when regular comics were 40-cents, but it was money well spent. Rogers’ full-color cover was an expressionistic image of a crying eye and the silhouette of a corpse (a teardrop falls on the dead body) were the main image. The cover itself, which didn’t feature the main characters, reminded me of a Saul Bass film poster.

The book opened with Denning and Rainer in the South Bronx trying to save the kid of a friend from joining a vicious street gang. There was also a parallel narrative of a murder in progress that was stylishly weaved into the narrative, a killing that would become their main case. In classic noir fashion there is a lot mixed into this bubbling brew including Rainier’s divorce (and weird sexual thoughts), Denning’s guilt over killing a teenage gang member and their shared plight of having little cash as they strived to survive in money makin’ Manhattan.

Though I and other Rogers’ enthusiasts (Kelley Jones, John Jennings) loved everything about the book, Comic Journal critic Kim Thompson was especially unkind to the art in a petty review where he claimed that the artist “simply cannot draw very well.” On the other hand, Starlog magazine editor Howard Zimmerman wrote that, “(Rogers) use of light and shadow in the delineation of people and perfectly rendered New York locations mark this volume as his best work to date.”

However, for whatever reasons, though Rogers continued working separately with Eclipse on interesting projects (Scorpio Rose, Cap’n Quick & a Foozle) twelve years passed before he and McGregor collaborated again. A second Detectives Inc. book A Terror of Dying Dreams, drawn by Gene Colan and published directly from his pencils, was published in 1985. It was the beginning of a long partnership that included the two private eye mini-series for Nathaniel Dusk (Lovers Die at Dusk and Apple Peddlers Die at Noon) for DC Comics and the childhood remembrances book Ragamuffins.

Still, McGregor and Rogers not doing another Ted Denning and Bob Rainier graphic novel was the equivalent of Steely Dan recording one brilliant album and breaking-up. These days 77-year-old Don McGregor is still writing, attending comic cons and reaching out to fans via Facebook, while Rogers died in 2007 from a heart attack. He was 57. At the time of his death, he and Steve Englehart were working on a new Batman story. More than a few of Marshall Rogers old friends and collaborators have publicly suggested it was the cigarette smoking that finally did him in. “It should be noted that he never once looked like it was affecting him, but clearly it did,” Englehart said in 2020.

___________________________________

The author wishes to thank his Facebook friends at Art of Marshall Rogers who helped me research this story: David Donovan, Thom V. Young and Andy Mangels.