When I tell people I’m writing a mystery series that features jigsaw puzzles, the reactions fall into two categories.

“I love jigsaw puzzles!” say some folks—my people.

The others offer pained smiles and a non-committal, “Good for you.” I understand that they’re not puzzle fans. In fact, some people experience anxiety when faced with the task of fitting hundreds of puzzle pieces together on a table. Hundreds of pieces—maybe a thousand! I’m not hurt by the fact that they’d rather have a root canal or pull weeds from their garden. To each her own.

While puzzles don’t appeal to everyone, I am encouraged by the popularity of online puzzles. The daily crossword, Sudoku, Spelling Bee, Wordle, Connections or some assortment of online puzzling are a part of many daily rituals, and a quick puzzle on my cell is a great pastime while waiting for the world to turn.

Jigsaw is my main jam. When jigsaw pieces are scattered over the surface of my puzzle table, I fall into a zone of relaxed observation, calm but ever vigilant for a puzzle piece with the perfect color or shape or texture. There is a tactile satisfaction in jigsaw puzzles, and I sometimes wonder if there’s a hand-to-brain connection that helps the puzzler feel her way to the placement of a piece. In puzzling, diligent search is always rewarded…eventually. When the right piece snaps into place, there’s a dopamine release – a surge of the human body’s natural feel-good hormone. This moment of contentment leads to the search for the next puzzle piece, and soon the bigger picture comes together with a hum of satisfaction. Rinse and repeat.

A puzzler’s sense of curiosity, craft, and satisfaction often parallels the feelings evoked by pursuit of the killer in mystery novels. There’s an addictive engagement, a drive toward completion, and a dopamine rush when a word or puzzle piece or clue falls into place. And isn’t every sleuth solving a puzzle?

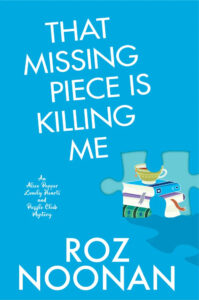

When I started writing the story of Alice Pepper, a librarian of a certain age who teams up with her offbeat family and friends to find a killer, it seemed fitting to make Alice and her gals jigsaw puzzle fans. Puzzling in Alice’s kitchen is not only a sort of therapy for these women; it also gives them a chance to discuss elements of the crime, piecing together personality quirks of suspects and other evidence they’ve collected along the way.

Alice and her friends are not alone in their love of puzzles. In these five mysteries, puzzles figure prominently in the thread of the plot.

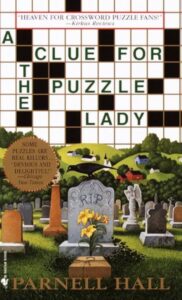

A Clue for the Puzzle Lady (Puzzle Lady Mysteries #1) Parnell Hall

Crossword puzzle clues are provided by the killer to prod the famous gray-haired Cora Felton, who is not a detective but writes a regular crossword feature in syndicated newspapers. Everyone in town thinks that the solution of the killer’s clues will solve the crime. The surprise is that Cora is terrible at solving or creating crosswords, but fairly insightful at solving murders. With the help of her niece Sherry, the crossword genius, the franchise is saved, giving Cora the freedom to chase real-life clues and gather evidence. Hall’s series went on to include 18 books, with a crossword puzzle in each book and a slew of murders in a small Connecticut town. Did it run too long? Not if you enjoy a pushy woman with a tired wardrobe, a highball glass in hand, and the nerve to pursue a clue in a back alley or graveyard at night. Hall admitted that he struggled with crosswords but wanted to write about a silver haired lady who published a puzzle a day. He used his weakness with crosswords as inspiration to create a “Puzzle Lady” forced to conceal her own inadequacies. It’s worth following Cora Felton, and the crossword puzzle in each book is a bonus.

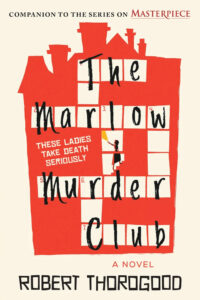

The Marlow Murder Club, by Robert Thorogood

Situated in a comfortable house on the Thames in a town she loves, 77-year-old Judith Potts is happy with the independence of her retirement. She has parttime job setting crossword puzzles for daily publication, she can drink as much whisky as she likes, and she doesn’t have to answer to any man. But her peace is interrupted when she hears her neighbor being murdered. When the police err in finding the killer, Judith bonds with two other women in Marlow who become aware of similar killings. Although the women work as a team, it is Judith’s awareness and expertise on everything from historical weaponry to pop culture that keeps her piecing clues together. This puzzle maker’s ability to solve puzzles and interpret patterns and archetypes bring clarity to the puzzle of these killings.

The Puzzle Box, by Danielle Trussoni

Puzzle master Mike Brink is a puzzle himself. As a teenage football player, he suffered a traumatic brain injury that transformed him into a mathematical genius with extraordinary cognitive skills. He now creates number puzzles for The New York Times. (His Triangulum is included in the book.) Brink is summoned to Tokyo to unlock a mysterious puzzle box that is so complicated, he may be the only one who can figure out how to open it. Created in Japan in the 1800s, puzzle boxes were used by workers and craftsmen to lock up their tools. Over the years, puzzle boxes grew in sophistication and danger. Many are rigged with tricks, booby traps, and poison. The stakes are high, as the two puzzlers who attempted to open the box before him have died, and the legendary Dragon Box is rumored to contain a key to an Imperial treasure. In the tradition of The Davinci Code, this thriller relies on deciphering archetypes, culture, and patterns. It’s fascinating to walk in the shoes of a compulsive puzzler who longs to be “normal.”

The Christmas Jigsaw Murders, by Alexandra Benedict

When Edie, a puzzle expert and Christmas curmudgeon receives a handful of jigsaw puzzle pieces showing a crime scene along with a note threatening multiple deaths before Christmas, Edie must break out of her ennui and inform the police. Then an injured crime victim is found with another jigsaw puzzle piece in hand, and the race is on to find more pieces of the puzzle and gather clues to prevent the murders. All before Christmas. In the spirit of searching for the Christmas pickle, the author includes a handful of puzzle games with clues that are interspersed throughout the text. Puzzle fans can search for embedded anagrams of Charles Dickens titles, hints of a popular Christmas song and its singer, and various references to Dickens.

The Busy Body, by Kemper Donovan

When a ghost writer embeds with a failed presidential candidate in snowy Maine, the two women ally to search for the killer of a neighbor. The true crime pursuit in this story comes through the ghost writer’s systematic introduction to possible suspects — characters in the midst of family dramas, personal struggles, and dark secrets. It helps that these interactions are amplified by the delicious perceptions of the unnamed ghostwriter. As each suspect is introduced, the author adds them to the plot like a block to a Jenga tower, which begins to waver when we slide blocks out or add heavy evidence later in the story. And then comes the small block that seems inconsequential at first. Instead, it’s that “aha” moment, a surprise twist that sends the tower tumbling, all but for the one block that lands in your hand. If Jenga is not your puzzle game, you could compare The Busy Body to a round of Clue in which evidence mounts quickly as you breathlessly wait your turn to announce: “It was Professor Plum in the parlor with a candlestick!” Or an Agatha Christie mystery in which clues are dropped throughout the narrative, but you don’t see them until you’re looking in the rearview mirror.

Isn’t that the moment we crave? That last puzzle piece snaps into place. The culprit is revealed. “Aha. Yes!” The End.

Time to crack open another.

***