The first time I read Frankenstein, I was unimpressed. I was freshly fifteen, slogging my way through a series of classics for English class, and desperate to be spending my time finishing up Buffy or The Vampire Chronicles instead. I found Victor Frankenstein relatable enough in the beginning; like him, I was a precocious (read: terribly conceited) student, determined to make my mark as a scientist. But as the book went on, I found him more and more pathetic in his failures and his self-loathing, unforgivable in his choice to abandon his creation – not least because, if he’d only stuck with his monster, I was sure, it would have made for a far more interesting story. I finished the book, answered my reading questions, and promptly forgot about it.

And then, later that same year, I realized I was queer.

#

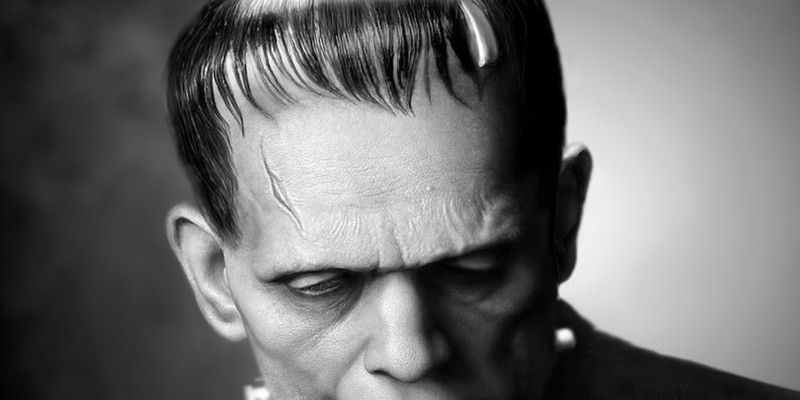

Queerness and horror have a long and complicated history. On the one hand, queer characters have often been used as props to shock and revolt audiences – but on the other hand, horror has also allowed queer creators to express themselves more freely through the lens of metaphor and the plausible deniability of a genre whose whole purpose is exploring forbidden topics. Frankenstein itself is entwined with queer history, too; James Whale, the first director to bring Frankenstein to the silver screen (as wildly different from the book as his adaptation was), was openly gay, and recent evidence suggests that Mary Shelley herself may have been bisexual.

There is something about Frankenstein’s creation – and, I think, about monsters in general – that speaks deeply to the queer community. It’s in that feeling of being unnatural, unattractive, unlovable; it’s about being abandoned by your creator, shunned by society; it’s about the unspeakable sorrow and rage that festers in one’s heart at this kind of treatment. I see it, too, in the monster’s terrible loneliness and desire for partnership; “Shall each man,” he says, “find a wife for his bosom, and each beast have his mate, and I be alone? I had feelings of affection, and they were requited by detestation and scorn.”

I spent my early teenage years desperate for a boyfriend. That I couldn’t seem to find one, while all my peers juggled relationships with what seemed to me shocking ease, seemed to speak to some kind of awful flaw in my body or soul. The realization of what that was came to me not like a lightning strike but like a creeping sense of dread, a series of helpfully informative Tumblr posts haunting me late into the night. I tried on several labels over the next few years – asexual? Homoromantic? Demiromantic? Gray-aroace? – eventually settling on simply queer, which allowed me to be a broad hand-wavy combination of all of them. The one thing I knew for certain was that the normal, picket-fence life I’d thought I’d had ahead of me was gone; now, I was a dead end, an anomaly. Our ultimate purpose, after all, as far as nature is concerned, is to reproduce – if I couldn’t do that, what kind of unnatural creature was I?

If I have to be a freak, reads one particularly fraught teenage diary entry of mine, why can’t I at least have cool vampire teeth?

#

Some years later, armed with a perilous sort of self-acceptance and a brand new gender crisis, I revisited Frankenstein – and felt like I was reading a whole new story. For one, I found Victor a lot more relatable, now that I’d abandoned my own lofty scientific dreams; after two years and a great deal of crying at my therapist, I’d been forced to admit that, despite my love for math and science, my fragile Victorian disposition was not cut out for the stresses of engineering. As Victor retreated to the wilds of Scotland to recuperate, I had retreated to the social sciences. As for the monster, whose long monologues my teenage self had skimmed, his rage and sorrow and loneliness hit my older, queer self like a train.

In a fascinating class entitled Gender and Science Fiction, I became acquainted with Susan Stryker’s My Words to Victor Frankenstein Above the Village of Chamounix: Performing Transgender Rage. In this revolutionary essay – now approaching its twentieth anniversary, and as relevant as ever – Stryker, a trans lesbian and activist, lays out all the ways in which transphobes have identified transgender existence with monstrosity in the past: as a “‘necrophilic invasion’ of women’s space,’ a threat to morality, a deformity, a perversion. Stryker mourns the effect this kind of hostility has had upon the trans community, driving many to suicide. But, at the same time, in a blaze of glorious rage and pride, Stryker reclaims this imagery: “The transsexual body is an unnatural body. … It is flesh torn apart and sewn together again in a shape other than that in which it was born. … I will say this as bluntly as I know how: I am a transsexual, and therefore I am a monster.”

These words struck me to my core, and cemented my new love of Frankenstein forever. And later, when I realized I wanted to write a spin-off of the novel, I knew this was the perfect opportunity for me to play with some of those themes of monstrosity and queerness I loved so dearly.

#

Mary, the protagonist of my novel Our Hideous Progeny and the great-niece of Victor Frankenstein, is a sharp-minded and sharp-tongued young woman desperate to make her name as a palaeontologist. This choice of career was inspired by another college class, one on nineteenth century science, in which one of our lectures focused on Victorian paleoart – a.k.a., pictures of dinosaurs. These gorgeous, Gothic, egregiously inaccurate illustrations were scientists’ earliest attempts at imagining what the ancient past might have looked like; or, in other words, their earliest attempts at bringing these long-dead monsters to life.

That was where the idea for the novel started: as an exploration of how some Victorian descendant of Frankenstein might go about actually bringing a prehistoric reptile to life. But as I expanded it into a novel, I realized I also wanted to tackle some of Frankenstein’s weird ideas about gender. Despite Mary Shelley’s widely-accepted status as a feminist icon, I’ve always found the female characters of Frankenstein disappointing; Elizabeth, Justine, and Victor’s mother are cardboard cut-outs, existing to comfort Victor or haunt him with their tragic deaths. Pure nature vs. corruptive knowledge is a major theme, with one common reading being that Victor’s crucial mistake is in trying to “appropriate” the natural, feminine domain of childbirth by way of the artificial, masculine domain of science. I was spitting mad, the first time I heard this interpretation; to me, it smacked of sexism and bioessentialism, that woo-woo way that TERFs and conservative Christians alike have of romanticizing pregnancy as some kind of feminine communion with nature, rather than one of the most arduous processes a body can endure. Did Shelley, with her proto-feminist mother and her tragic history of miscarriages, truly intend such a reading? I couldn’t know; all I knew was, I wanted a protagonist who would rip that particular interpretation to shreds. A woman who felt herself more “naturally” inclined to science than to motherhood, who was harsh and angry rather than gentle, who (spoilers!) would eventually leave her husband for another woman.

In many ways, although Mary is cisgender, I felt as though I were writing a trans character. In the Victorian age – and well into the twentieth century – gender and sexuality were closely entwined; gay individuals were viewed as sexually “inverted,” with sapphic women thought to possess some kind of masculine aspect that explained their attraction to other women, and vice versa. Thus, to be queer at all was to be gender non-conforming, and to be gender non-conforming was to be queer. Mary, with her attraction toward other women and her desire for a career in science and her aversion to pregnancy and motherhood, is queer in many ways by Victorian standards, a perversion of all that nature supposedly intended her to be.

And here, of course, was the revelation that made me sigh “Oh!” aloud: Mary would be not just Frankenstein’s heir, but his creation’s as well, an amalgam of monster and scientist both. Like Victor, Mary is ambitious, driven, arrogant; like the monster, she is an outsider, prejudged for things she cannot control, vacillating between self-loathing and rage at the unfair hand the world has dealt her. This was the key, I felt, that tied the whole book together.

If there is one major difference, however, between Mary’s story and that of Victor or his creation, it’s the ending. Both Victor and the monster die at the end of Frankenstein, fading tragically into the arctic sunset, but I couldn’t bear to do the same to Mary. Perhaps (despite my love of tragic queer horror), it would have felt in this case too close to burying my gays; perhaps I simply felt that, after all her hard work, Mary deserved more. Whatever the case, it felt right – like a love letter, almost, to myself and to all the other unnatural creatures out there – to give her a happy ending. In the words of Frankenstein, “It is true, we shall be monsters, cut off from all the world; but on that account we shall be more attached to one another.”

###