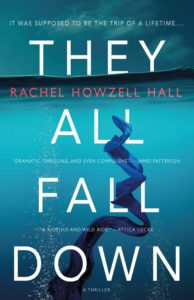

Rachel Howzell Hall exploded onto the procedural scene in 2014 with Land of Shadows, a thrilling debut that introduced to readers Eloise “Lou” Norton, an African-American LA homicide detective, in a predominately white male field. Stunningly prolific, Hall’s writing is filled with memorable characters and riveting plot lines, rooted in the complex world around us: arson, infidelity, gentrification, murder. In addition to publishing a novel a year since 2014, she has collaborated with James Patterson in 2017 with The Good Sister: a cheating husband has been found dead, what will a loyal sister do? Her latest novel is the stand alone, They All Fall Down, a twist on the Christie classic, And Then There Were None. We sat down for brunch one wet LA morning. Our conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Désirée Zamorano: Let’s talk about your latest, They All Fall Down. Why this book?

Rachel Howzell Hall: The truth is I had wanted to write a story like this since seeing “Seven” where these people are getting killed according to their sins. As a child of the church the idea of punishment has always fascinated me. In college I read Dante’s Inferno, with its certain levels of hell. As part of my education in writing mysteries I read Agatha Christie, and the first that I read was And Then There Were None. Mix together my religious background, my classic education, combined with pop culture: I wanted it to do it all, I wanted to do this story. That’s what made it fun.

Another reason why I wrote this is the original story is, of course, all white, and it’s all about class. When I was over in the UK for a book tour for Land of Shadows, I did an interview with Radio 4 Woman’s Hour. I talked to the hostess about growing up and going to college and she stopped me. “You went to university?” she said, surprised. I guess stations in life over there are stations for life, and poor kids don’t go to college. Whereas here, that’s how you can get ahead.

What I wanted to do was to take that very English story and make it a very American story, across class, with a more diverse cast. I wanted to play with the idea of how you, as a person of color, can be on an island in the middle of nowhere and there is still an authority figure who wants to harm you. I also liked the idea of taking a story that was once named Ten Little Niggers and revising that. That’s a funny thing: when 1940s America tells you your title is too much? Did you know that?

I had no idea.

Her American publisher said, we can’t do that. That’s who made her change it. And we’re talking the 1940s!

On another level I also wanted to get the reader thinking, does the protagonist, Miriam, deserve to be on this island? I myself, as a mother, have mixed feelings about her being on this island. I wanted to explore how those of us who love people will do things that we never thought we’d do, all in the name of love.

Thinking about my own writing trajectory, and casting about for writers who resonated with me, I’m wondering if you have a few of your own?

Around 1994, 1995 there was a period of time when Terry McMillan and Walter Mosley exploded at the same time: a Black contemporary story with Waiting to Exhale, and then a private eye who solves crimes on Central Avenue. During high school I had lived in a neighborhood off Central Avenue! So both of these things happening at the same time, which was kind of cool. Around that time I’d also landed a job at PEN Center USA West, where I met Gary Phillips. He, along with Bebe Moore Campbell and Jervey Tervalon were the first Black working writers I met. I was able to see that it was something I could do.

You were first published in a different genre. How did you move into procedurals?

My first book deal in 2002 was for literary fiction, A Quiet Storm, which got some great acclaim. But I’d also always wanted to write a procedural. It was just that procedurals were mainly white male type of genre. So I didn’t do it then! Plus I wasn’t a cop and I didn’t know anything about that kind of life.

“[A]gents and editors told me my voice wasn’t urban enough, or gritty enough, or black enough. I didn’t write the stories that they thought sold.”My first kind of dip into a procedural was self-published in 2012 with No One Knows You’re Here, featuring a newspaper reporter (she later becomes Lou Norton’s best friend) My literary agent and I had broken up by then. That novel did okay, but not enough to land another deal. My writing efforts continued while publishers were still looking for the next Sister Souljah, that kind of east coast urban face of the black experience. At that time both agents and editors told me my voice wasn’t urban enough, or gritty enough, or black enough. I didn’t write the stories that they thought sold.

This is a familiar publishing story—not fitting the slot they’ve already constructed for you.

Right, but I kept writing. As I was working, writing and getting rejected, and writing some more, I had some life issues. I was pregnant with Maya, at age 33, and I was diagnosed with breast cancer. I had a lumpectomy six months pregnant. Three years later when they set me up on tamoxifen, I began thinking about my mortality: it was very possible that I would not see fifty. I thought about all the stuff I wanted to do before dying.

“I realized that before I died I wanted to write a mystery series with a female cop. This would be for me…”I realized that before I died I wanted to write a mystery series with a female cop. This would be for me, not for an agent, not for an editor. I had absolutely nothing to lose. With the blessing and support of my husband, David, I went to conferences, Left Coast Crime, Bouchercon, Writers Police Academy. I started rereading Chandler forensically. Michael Connelly, all the LA stories, I started reading them. I started thinking about who I wanted to feature.

I really feel, if we ‘do the work and abandon expectations’ we renounce the weight of our own expectations, and get down to the joy of writing.

Right! And as I read, I planned. I knew I wanted a Black woman like me, who grew up in my neighborhood, who went to college where I went, who pledged to the sorority that I did, but that she would be a victim of a crime against her sister, and she would committed to find her sister.

So this was part your inspiration and motivation for Lou.

Actually Lou is informed by the lives of all the women I know, all the women I don’t know but have observed in malls and public places. She’s me in terms of growing up in “the jungle” in that neighborhood. A kid of aspirational parents, who knew they were working class, but whose kids weren’t allowed to “act poor.”

I wanted her to be dynamic. And whenever I start a story that’s when I outline it to see where she should be in it.

After I wrote that first draft I signed with my agent, Jill Marsal, who is just a magnificent agent. Happily we landed with Forge. Now every novel I do with Lou, every novel I do, I have an idea of an issue that bothers me, and that I want her to avenge in many ways. In all the novels, I’m casting about for issues, and that’s the wonderful and awful thing about what I do, there are so many issues that are inspirational, not in a good sense, but terrible things for mystery writers to take on. For example, in They All Fall Down I looked around and bullying was happening, I read the news and someone had just died in Las Vegas from over-eating at an all-you-can-eat buffet. These issues became part of my work.

I’m also fascinated with your collaboration with James Patterson. How did that unfold?

It happened 3:30 on a Friday afternoon. Jill called and said “I just had an interesting conversation.” That’s when she told me that Trish Daly, Patterson’s editor, had called her to say they had enjoyed my series and wanted to know if I might be interested in collaborating with Jim on a BookShots. That’s 30,000 words.

I said, I’d think about it. I was exhausted, at work, the end of the work week. One more thing to do! I told my husband and said I was thinking about it, and he was “Are you crazy to have to think about it?” Yeah, you’re right. I am crazy. I was just tired (laughing).

It was a great experience. I pitched a story, they worked with it to make it a James Patterson story, and he liked it. I started writing it, 10,000 words at a time, in three chunks.

It taught me how to get in and out of scenes quickly; how to have that cliff-hanger ending for each chapter.

That’s terrific.

It’s one of those things that I have to remind myself that I’ve done! You know, sometimes you think, I’ve done nothing. Yes, that was good, but what about now? We’re always moving on to the next thing…But there’s a part of me that’s always thinking, what’s happening right now? What haven’t I done better? Why aren’t I like that right now? That must be because I’m not working hard enough.

When you say, ‘why aren’t I like that,’ we have to remember there’s a structure in place preventing some of us from being there.

Once again. Some people get to be in The New Yorker. Some people get to tell the same story that’s been told, and use Girl in the title or Woman in the title…

So how does this work? If a white woman can’t even get a break, what does that say for those of us as women of color who are trying to write stories that may sound familiar but are coming totally from a different view point. The Lou Norton series follows a female detective and there are lots of stories of female detectives but there aren’t many female detectives who grow up in the part of Los Angeles I know—with her backstory, with her obstacles…

In addition to your writing career you have a full time job, a family, a life. You don’t think you get a lot done, I think you get a lot done. How do you do it? Goddess writer tips, please.

“I write, and I write on a dime. That kind of muscle means I don’t know what it is to say, ‘Oh, I don’t feel like writing today.'”My dog wakes me up at 5:15. I take her out and get ready for work. I get out of the house at 5:40. I get to work at 6 and I write all the way to 7 o’clock. Then at lunch time I write or answer emails—if Maya has soccer practice I do my steps around the track, go back to my car and write some more. If my brain is fried I’ll transcribe. I don’t write on Saturday, that’s my day of rest.

This morning (Sunday) I woke up at 5:15, I had my coffee and I wrote until about 8. And that’s it.

Part of my success is that I’m blessed with my daytime job. I write, and I write on a dime. That kind of muscle means I don’t know what it is to say, ‘Oh, I don’t feel like writing today’ or ‘Oh, I don’t know what to write.’

Is there a crime you still think about?

For me although I write about the neighborhood I grew up in, my first freak out with crime was back in the late 70s. My brother was part of the California Boys Choir—alongside many moneyed families, like the Van de Kamp families. Noah, part of the choir, was the son of the Neutrogena family and lived in Beverly Hills. Noah and his mom were at home and someone broke in their house and killed them all. This was back in the late 70s. I remember the picture in the LA Times, in the Metro section. Even as a kid that was the first section I’d read. Here they were, all dead. That crime has stayed with me. To this day, that home invasion. The husband, the dad, was initially suspected to somehow be involved. Turned out it was a jealous business rival.

What’s ahead for you?

I have a couple of projects. One I hope breaks out, one just for myself. With the political climate I really look forward to a lot of art coming out of this. I’m also looking forward to our stories; there’s an aspect of our voices to see what we do with what’s going on, to see what we do with retelling stories that people have heard over and over again. Other writers get to tell their stories over and over again, and I want us to be able to take these stories from our point of view, because it’s coming from a different experience in this country. Everyone’s talking diversity right now but I’m not convinced it’s happening as much. We’ve had some success, with Tayari Jones and An American Marriage, and Kellye Garrett; I fear that now that some boxes have been checked, the boxes have been checked and we can return to our regularly scheduled program of leaving people out. We have to have more than #weneeddiversevoices. We need support! From our editors and publishers convincing readers that our stories are engaging, entertaining, and that they matter.