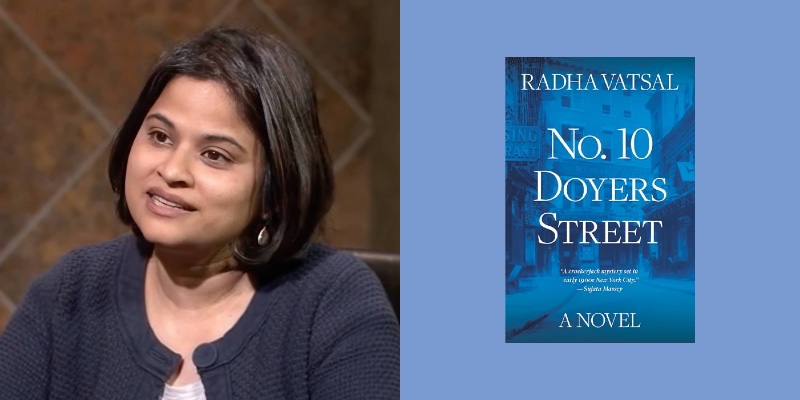

No. 10 Doyers Street is the new historical mystery novel from Radha Vatsal. Radha lives in New York City, and like her previous two books, this one is set in New York. But it is a New York City we don’t see that often in fiction. Set in 1907, her book focuses on the very early days of New York’s Chinatown, but as seen through the eyes of a woman, a journalist, who herself has come to the United States from India. This rarely explored perspective is one of the best and most interesting things about the book, along with the usual excellent writing and plotting and characterization Radha brings to her novels. No. 10 Doyers Street is an engrossing read, and I was glad to be able to talk to Radha about it.

Scott Adlerberg: I just finished reading No. 10 Doyers Street, and I enjoyed it very much. It feels like both a continuation of what you’ve done in your earlier two novels and a branching out into new territory. It’s a historical novel set in New York City, like your two Kitty Weeks books, and your main character as in the previous books is a journalist. But here you introduce a new protagonist, Archana Morley, who in 1907 is one of the relatively few people from India living in the city. Kitty is a women in the WWI era working in a male-dominated field, and thus something of an outsider, but she is white. With Archana, considering her background and profession, she’s a kind of double outsider. I know of course you were born and raised in Mumbai, India, and have lived in New York for a long time, but what was it now that made you want to turn to a character with a background similar to yours, albeit at an earlier time?

Radha Vatsal: Hi Scott, that’s a great question. No. 10 Doyers Street is set in Chinatown in the early 1900s, and it tells the story of the legendary gangster, Mock Duck, and his young daughter. For a few years (!) while writing the novel, I thought I had to have a white narrator simply because I couldn’t imagine anyone from India in New York City during that time period.

The trouble this caused was that I felt that all my insights into Mock (and he’s a real, historical character) were the result of my Indian heritage. I felt I could see him as a person and not just as a villain or a caricature because of my own experiences coming to the US from India as a teenager and having to negotiate life here. And so, attributing my thoughts and feelings to a white narrator in this instance really required a lot of literary gymnastics–and they didn’t turn out so well. I kept writing versions of the novel that didn’t work. Finally, in desperation, I decided what the heck: New York City is a port city of 2 million people (the population in the early 1900s) – surely there could be one just one Indian person among those millions. And while I was at it, why not make that Indian person a woman? Amazingly, once I took that imaginative leap, I discovered that there had in fact been all kinds of people from India who traveled to and lived in America during the 19th and 20th centuries. And some of these people were indeed women and they wrote about what they saw and learned in this country. And that’s how the character of Archana Morley was born. She is the result of writerly desperation. The story demanded her. You might say Mock Duck brought her into existence to tell his story.

Scott: Before we get to Mock, can you talk a little about some of those people from India who traveled and lived in the US in the 19th and early 20th centuries? You reference a couple of them in the book. I found all those parts quite interesting and indeed Archana as a character, her background, was fascinating, in part because an Indian protagonist in a novel set at that time in the US is not one I’ve come across before. I’m sure there are books set in that time frame with Indian immigrants as characters and even main characters, but in mainstream American fiction at least, I would guess they are still relatively rare. She has a particular background and a great outsider’s perspective grounded in that specific background.

Radha: The earliest record of a traveler from India to the US that I’ve seen is a diary by a Zoroastrian/Parsi man who visited the US during the Civil War. He travelled around the country, stayed at fancy hotels, noted his observations about New York City, and even met President Lincoln! The two women who Archana references in the novel are Anandibai Joshee and Pandita Ramabai.

Anandibai Joshee came to the US in the 1880s to study medicine at the Women’s Medical College of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. She sent letters back home to India, which her husband published. They give us a sense of what she thought about the US and how she managed. It was difficult for her with her vegetarian diet but the Dean of college, Rachel Bodley, was incredibly kind to her and looked after her like a daughter.

Here’s a photo of Anandibai (on the left) with two of her classmates, so you see she wasn’t the only student from abroad.

She also befriended a woman from New Jersey, Theodocia Carpenter, whom she called “aunt.” And when Anandibai died – right after she returned to India – her husband sent her ashes to New Jersey, and Mrs. Carpenter buried them in her family plot in upstate New York.

The other woman who Archana refers to is Pandita Ramabai who traveled through the US for a couple of years during the 1880s. Pandita Ramabai was a scholar and a fearless person. She gave talks to packed houses across the country (north, south, east and west) about the plight of child widows and child brides. She met the American women’s rights activist, Frances Willard, and she met Harriet Tubman – who was pretty old by then. And when she returned to India, Ramabai wrote a book explaining America to her Indian readers. The English translation is “Conditions of Life in the United States.” It’s an incredible book, originally published in 1889, and the fact that Ramabai wrote it is even more incredible. It’s still barely known today.

Archana shares some traits with these women: she’s highly educated and independent. But unlike them, she comes to visit America and stays on. She builds a life for herself in New York and when she’s at work, she wears men’s clothes so she can get around without attracting much attention. Although Archana is fictional, I have to believe there must have been other women like her we’ve never heard about.

Scott: So, yes, as you say, through Archana, you found a way to look at Sai Wing Mock, aka Mock Duck. He lived from 1879 till 1941 and, to quote Wikipedia, he “was a Chinese-American criminal and leader of the Hip Sing Tong, which replaced the On Leong Tong as the dominant Chinese-American Tong in Manhattan Chinatown in the early 1900s.”

Now obviously there’s a long tradition in books of sinister Asian, or specifically Chinese, criminals, Sax Rohmer’s Fu Manchu being the most famous. And in your novel, you get into the image prevalent then among many Westerners of the so-called inscrutability of Asians, people living in their own mysterious world there in New York’s Chinatown. These are the early days of Chinatown and in terms of space, it took up – what? – a few square blocks? Not like the sprawling New York Chinatown of today. But what made you interested in Mock Duck as a character to the point that you wanted to center a whole novel around him?

Radha: I came across Mock Duck quite by chance. I was searching for articles in the New York Times historical database, when I stumbled on a story from 1907 about how the Society for the Prevention of Children raided Mock Duck’s home and took away his six year-old daughter. The story was filled with racist stereotypes – but even the journalist who wrote it had to acknowledge that Mock Duck loved this little girl and that the gangster lived in a spotless home with his wife and an Irish maid, and that his daughter was well looked after. Well, that got me hooked. One thing I quickly learned was that the Tongs weren’t primarily criminal organizations. Like Tammany Hall for the Irish, they also offered aid and helped newcomers find a job and get a foothold in this country.

Mock was a young guy – he was in his twenties when he rose to power – and he was ruthless. He was also extremely smart and used the law to get out of trouble. So there are all these different elements to him that I found fascinating: he’s a gangster and a devoted family man, a ruthless killer but one who has never yet been convicted. He looms large in the public’s imagination and is always getting blamed for every criminal act in Chinatown, but he remains steadfast in his denials. And no matter how implausible, he always says he never did anything.

Scott: In the background of the main plot, you have the Harry Thaw murder trial going on. Thaw of course had shot famous architect Stanford White in full view of numerous witnesses on the rooftop of Madison Square Garden. This had to do with a couple of things, one of which was Thaw’s obsession with the relationship White had had with Thaw’s wife, Evelyn Nesbitt. The connections between those three were tangled, but Thaw clearly was an unbalanced and dangerous person. His trial was called “The Trial of the Century” even then. Archana is covering this case, which the public is fixated on, though she becomes less interested in it as it goes along and as she gets more interested in what is going on with Mock, Mock’s daughter, and Chinatown. The inclusion of this trial in the novel reminded me of course of E.L. Doctorow’s Ragtime, where the White killing plays a major part. Doctorow was a great writer of historical fiction and helped make popular the mixing of real life people and fictional people in his novels. I was wondering who some of your favorite historical novelists are and what draws you to setting your stories in the past.

Radha: I’m really glad you mentioned Doctorow. I loved Ragtime, which I read in my twenties. But it’s another one of his novels, The Waterworks, that actually inspired me to write historical fiction and to focus on historical fiction set in New York City. The Waterworks takes place in NYC in the 1870s and involves historical characters like Tammany Hall’s Boss Tweed. It’s told from the perspective of a newspaper editor and the protagonist is one of his freelance journalists. The main characters in all my three novels are journalists too – but I don’t think that was a conscious decision I made after reading The Waterworks. But I definitely remember being blown away by how New York City functions like a character in the novel (it’s more of novella, actually) and of course, Doctorow’s writing is brilliant. Anyhow, I highly recommend the book if you haven’t read it.

I’m drawn to setting my stories in the past because the past can help us understand the present better. And in fact, I’ve been thinking about The Waterworks a lot recently because in the novel there’s a mystery around these old very wealthy men who want to live forever… And those 19th century business titans remind me of our current batch of billionaires.

Scott: Yeah, the comparisons we often hear now between the Gilded Age period of the late 19th century and our period do feel apt. And No. 10 Doyers Street of course has a lot to do with a subject of clear relevance today, and that’s immigration. Who are the people coming to live in the United States from other countries, should they be allowed to come at all, once they are here can they be considered “American” – the same issues argued about today are all at the center of your book. When you worked on this novel, and just in general when writing historical fiction, how much do you think of the present day and try consciously to tie the past to the event, if you do? No matter what your concerns about our contemporary time, you would want to get all your historical details right, I would think, and tell a compelling story that works on its own in its own time frame.

Radha: Absolutely. I’m drawn to incidents from the past because they speak to – or complicate – ideas we have today. But I never consciously try to tie them to the present. In fact, I make a strong effort to understand them on their own terms and present them as they would have discussed in their own time. For me, it’s boring to overlay contemporary ideas on to the past, and more than that, if we bring our current ideas to bear on the past, we risk missing what the past has to teach us…and that’s what I find fascinating. The things that happen in the novel, most of them, are historically accurate–and they’re stranger than fiction.

I really believe the past is a “foreign country,” as the saying goes. And when you’re in a foreign country, I think, as much as possible you should drop your preconceptions of how things ought to be and try to see things as they are. That’s what I try to do, and it’s the strangeness that ensues that makes writing (and reading) historical fiction so rewarding for me.

Scott: I couldn’t agree more with you’re saying about historical novels. It’s the strangeness of so much of history that’s one thing that always strikes me, the strangeness that’s there along with an unsettling familiarity. Is history going anywhere or is it essentially going in circles? As you say, you don’t necessarily have to invent or embellish much to get those qualities across.

Well, it’s too early to write a historical novel about our present times, speaking of “stranger than fiction”, but have you started working on a new project yet? Obviously, there’s a good bit of research that goes into the books you write – and I don’t know whether or how much you enjoy that part of the process in and of itself – but I’m eager to hear what you have in the works.

Radha: Thanks, Scott. I love the research or I wouldn’t do it! I always learn so much – more than I’m able to put in my books. Right now, I have a couple of projects brewing – one of which is a contemporary crime novel – which is definitely something new for me. It involves politics, naturally! But it’s still in its early stages… I’m also working on some non-fiction. Writing Archana made me realize that there are stories from my own past that I’d like to find a way to tell – for instance, coming to the US on my own to attend boarding school when I was sixteen, working as a Russian-English translator in Siberia during my twenties. But writing personal non-fiction (I wouldn’t strictly call it memoir) is a totally different beast. I’m still figuring it out. But it’s great to toggle between the two: fiction and non-fiction. You realize they’re not so far apart.