tl;dr: Research is hard, rabbit holes are interesting and twisty, and electric cars were invented a long time ago. Also, crooked cops are bad, whatever the era.

Spoiler alert: Wow, electric cars sure were invented a long time ago! And some serious points are made.

I spent this last week down a rabbit hole.

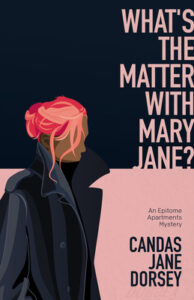

We’ve all been there. My last big dive before this was when I was looking up DNA for my upcoming mystery novel, He Wasn’t There Again Today, which will be the third in the Epitome Apartments novels, following last year’s The Adventures of Isabel and this year’s What’s the Matter with Mary Jane? (I’m tempted to post the results, but this travelogue is already pretty long.)

But the journey I will chronicle here is down what one might call a “civilian” rabbit-hole, as it was not initially research for a project. (Oddly, it turned out to be tangentially relevant to the new book, but that’s another story.) No, this happened when a folklorist friend asked online what our favorite murder ballads were, and I realized that I knew SO MANY MURDER BALLADS REALLY SO MANY!

Staggerlee, Brady, Ella Speed, The Cruel Mother, Banks of the Ohio, Soldier Soldier Will You Marry Me, and even some suicide ballads like Unfortunate Miss Bailey all swan around in my head for a day or so. It was real noisy in there for a while.

But for some reason “King Brady” infested, earworm-style, for a whole week. One day when I should have been writing, I upped-fluffy-tail and dived down the Internet rabbit hole—and am still chasing phantasms down little twisty corridors.

*

I started with the lyrics. Everyone who has researched song lyrics online knows that they are full of errors. People write them down as they imperfectly heard them, then other people cut and paste, and suddenly the “canon” version of a ballad has a great big malapropism right in the middle of it, creating a cascading generation error that upsets purists and detail freaks, but also means that all over the world, people are singing the wrong lyrics to a lot of folk songs. Which is pretty hard to do when the prevailing wisdom of folklorists is that there are no wrong lyrics, there are just variations, but thanks to the magic of the Internet, it’s now possible.

But never mind that now. We’re at “Brady, Brady, Brady don’t you know you done wrong…”, which is how I learned the song, almost 60 years ago when I was a kid.

Except we aren’t, yet. First we’re at “Twinkle, twinkle, little star”, because that’s how the song begins in several other versions. And suddenly (—sudden to me that is, though I heard the Tom Rush version decades ago, but it wasn’t the one I learned—), King Brady, crooked cop, has an electric car.

*

Allegedly, the song refers to an event on October 6, 1890, in St. Louis, Missouri, where a saloon fight resulted in the death by shooting of James Brady, a white cop. Despite some doubt about his guilt, including witness statements which attributed the fatal shots to the saloon owner, Charles Starke/Starkes/Starkey, William Harrison Henry (known as Harry) Duncan was arrested and tried, and after numerous unsuccessful appeals, one of which included the first black lawyer to argue before the US Supreme Court, he was hanged on July 27, 1894 at the age of 31. Starkes allegedly confessed on his deathbed to the murder, far too late to save Harry.

But is this really the story? In the versions of Leadbelly and others who sang and recorded the song, Brady was a cop and Duncan the bartender, already conflating the accused killer with the actual killer. However, in the first recorded version of the song, by white singer Wilmer Watts and his group, in 1929, Brady was a telephone lineman and Duncan was the cop. A Mrs. Tom Barrett told folklorist Dorothy Scarborough that it all happened, yes, but in Waco, not St. Louis.

Tom Rush recorded a beautiful version in 1963 on Got a Mind to Ramble, and Bob Dylan first recorded it around the same time, later released in the Bootleg Series in 2008. Leadbelly of course had already recorded several versions in the 1940s, and his are the closest to the one I learned in the 1960s. But the song has been recorded a lot of times, by everyone from Lomax in his convict field recordings through Dave van Ronk and Tom Rush and James Taylor (in 1970) to recent singers, and you can of course find a whole slew of proliferations on YouTube.

You can dive down this rabbit-hole yourself: check out Fresno State’s background on folklore and this deep dive into the many visions of the ballad. Here you can find more info about the true life crimes inspiring St. Louis’ turn-of-the-century ballads.

You can find the Wilmer Watts version of the lyrics here; or the more popular version here. Note that in the latter there one of those errors of lyric: the women really went home and “re-ragged” in red, meaning changed their clothing—but that site gets the rubber-tired hacks right. Other versions miss those “rubber-shod horses”, “high-tailed horses”, or “rubber-tired hacks” and settle for the square brackets of confusion instead. And here, Tom Rush sings “high-tailed carriages” (Dave van Ronk sings “high-tired carriages”) while the supposedly-transcribed lyrics say otherwise.

You can hear Leadbelly sing one version—no electric car—and Tom Rush sing another—with electric car. For fun, look at Rush’s 2014 version without car, but with a great, and funny, spoken bridge that completely departs from—and trashes—the historic record, while retaining the cop’s basic corrupt nature. (Or you can just do your own DuckDuckGo search, and enjoy.)

Probably my favorite write-up is found here, a concise summation of all the different historical realities that are at play when analyzing the song. I came to it after exploring all those points on my own, thus proving that there are few Internet rabbit-holes through which others have not hared their way. Footpaths and breadcrumb trails abound.

*

So far the journey was not too deep, and not too twisty—about as usual for this kind of thing—and if “close enough for folklore” isn’t a saying, it should be.

But alas, I was on a roll. Electric car? 1890?

You will already see that I’m not the first person to fixate on the electric car.

One version on Youtube accompanies the song with footage of early electric cars. This telling of the tale rules out the electric car altogether, with a pretty reasonable explanation. After all, if the bartender and the falsely-accused can be conflated, why not two James Bradys?

I was on a different route (pun unintended but fortuitous). Did 1890 USA even have electric cars? I discovered that yes, despite what “territorialimperatives” says, electric cars were being developed in the USA in 1890. The first electric cars were developed in Europe between 1828 and 1834, and there were several commercially viable versions thereafter, in the mid-nineteenth century (which is a surprise, actually, and if one is a car geek, there’s a side-tunnel there, but I was able to ignore it with application of a lot of “lalalalala I can’t hear you”s and a stern self-talking-to). The first electric car in the USA was developed by William Morrison in Des Moines, Iowa, between 1889 and 1891.

So in theory, a crooked cop in 1890 could have afforded a prototype electric car to drive around hassling saloon or “grocery” owners and patrons and prostitutes—or could have imported one at great cost. Or maybe not.

Or was it a police wagon Brady drove, as Morrison’s first cars were 6-passenger, and therefore the Des Moines police force could have been forward-thinking? Or maybe not. I was unable to discover online what was going on in the police department in Des Moines in 1890.

(Or was the telephone lineman driving a telephone company vehicle? —but let’s assume we’d be in a different story if we went there.)

So my favorite of these quantum-event-worthy story-lines is that Brady was a young, flashy crooked cop with a fancy modern car, and he threw his weight around a lot with the gamblers, saloon owners, and ladies of the night. Finally somebody shot him, which was kind of inevitable in the easy-gun culture of the time and place, and celebration ensued.

*

For the time being, I had enough of a tapestry of real and imagined connections to satisfy a fiction writer about what happened here. Alas, I also have a tapestry with a lot of loose ends. I am trying very hard to think of them as a decorative fringe. I know I can pull any one and find more intriguing stuff, but I am trying really hard here to write a novel instead.

There’s one last thing I want to talk about, which in the end might be my most important takeaway.

I heard this song a lot when I was a kid, learning it at about ten or eleven years old, a time when my brain was most likely to accurately archive lyrics and tunes (and boy howdy, I’ve got a lot of them in there). This was the “folk boom” of the 1960s, and in 1963 my older brother, who would become a professional musician soon, and older sister, who sang all her life, were part of “folk groups” all over North America that avidly searched the Lomax collection, the Child ballads, the works of Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger and Ronnie Gilbert, and any other recorded sources, looking for evocative ballads.

“Brady” was one of the ballads that got a lot of play.

Every time I heard anyone sing it, the introduction always was, “Here’s a song about a crooked cop named King Brady…”. The story was always that Brady had been paid off to let the game go on, and he broke in anyway, and died for it. Until I dived into that rabbit hole, I couldn’t find proof, but at least one of those sources above makes it plain: the conviction of Duncan was a race-related miscarriage of justice, and early performances of the song triggered rioting and protest.

Harry Duncan, a black man, was 31 when he was hanged, after four years of trials and appeals. That means he was 27 when he was arrested and convicted—some say framed—for the death of James Brady, a white cop who was labelled as corrupt and arbitrary and violent.

The ballad was a rallying point for protests about the mistreatment of black people by white cops. Does it matter if James Brady was only 31 years old when he died, just like the real Duncan? He’d still “been on the job too long”.

Was Charles Starkes white? That’s one of the loose ends I haven’t resolved yet, but I’m guessing maybe. I can’t find evidence either way. Maybe he just paid his protection, as the song suggests. But he was certainly sheltered from consequences.

Who shot whom during that storm of bullets in Starkes Tavern (or Grocery)? We will never ever know for sure, but contemporary evidence actually ruled out Duncan—evidence that the court refused to process, thus committing judicial murder. The only people to testify were cops.

From the first singer of the song, likely a black man in St. Louis somewhere at the end of or after the year of 1890, to my brother and sister, white kids coming of age in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada, in 1963, and through to me, almost 60 years later, still singing it, the through-line of this murder ballad was injustice: a crooked cop gets shot by someone who has been tried too hard and pushed too far.

The file history of a person is sometimes called “a legend”, and using the word in this way, I find it amazing that an accompanying “legend”, a provenance, has come down, with the ballad, in an unbroken line—and that “legend” is of a corrupt cop.

In the ballad, the shooter, Duncan, is clearly culpable. He ignores pleas from the wounded Brady and instead says angrily, “I shot King Brady, gonna shoot him again” and sometimes adds “cuz he’s been on the job too long!” (If he doesn’t, the women in the tale, possibly sex workers, stand around and urge Duncan to take another shot.)

Duncan is the hero of the tale for ridding the world of the corruption. The women, if they don’t urge the shooter on, may scream or cry during Brady’s shooting—but when they are sure he is dead, they go home, “re-rag in red”, and dance in the streets.

*

It’s ironic that in the ballad Duncan was conflated with Starkes and the wrongful conviction was turned into a false fact. But that doesn’t diminish the anger, or the impact, of that plaint against a dirty cop who went out looking “to shoot somebody just to see him die”, and may have been padding his pockets enough to lord it over the people from whom he was taking payoffs by buying a fancy new “’lectric car”.

The knowledge of and anger about police corruption (not new at the time, either) has been accompanying the song since it was written, not long after the event—so for 131 years so far. In 1960s Canada, a little white kid, me, got the message when I was eleven, which meant that I later understood events like the George Floyd murder in a lengthy historical context. Last week, fifty-eight years after I learned the song, I went down the rabbit hole to discover where my knowledge came from, to discover that it was a real thing, a call to action and anger, and that the provenance is clean and clear.

The message comes through.

They’ve been on the job too long.

Like, since at least 1890.

***