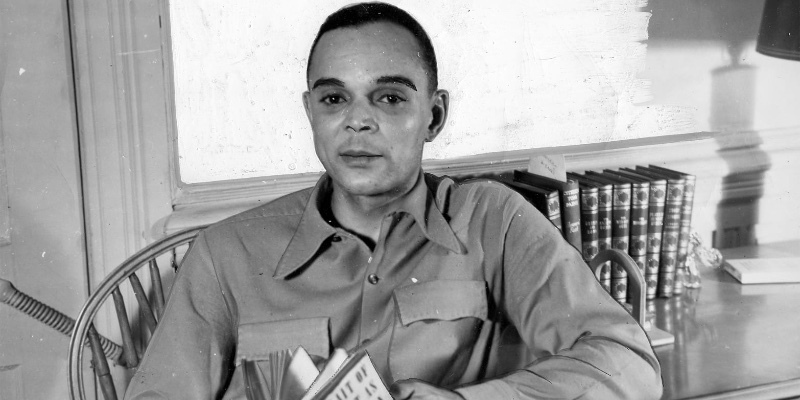

The best-known novels by Chester Himes are called “the Harlem Detectives” stories, which would seem to indicate that a couple of New York police officers are the stars of the series.

Far from it. After reading six of Himes’ novels, I think that the main character in these books actually is the Harlem of post-World War II New York City. Himes calls it “Harlem, USA.” It appears on nearly every page, teaching us about its people, its places, its ways, its woes, its diversions, its language.

Consider, from The Real Cool Killers, this loving description of the window display of what he calls Cohen’s Drug Store, which he places near 145th Street and Convent Avenue. (Yes, Himes is probably describing Mishkin’s, a block to the west at 145th and Amsterdam.) Behind the iron grill, we are told, are displayed

. . . electric hair straightening irons, Hi-Life hair cream, Black and White bleaching cream; SSS and 666 blood tonics, Dr. Scholl’s corn pads, men’s and women’s nylon head caps with chin straps to press hair while sleeping, a bowl of blue stone good for body lice, tins of Sterno canned heat good for burning or drinking, Halloween postcards and all the latest in enamelware hygiene utensils . . . .

At first, I thought this was just a thorough inventory of a passing sight that figures not at all in the larger story. But on second thought, I think it is an indirect way of reflecting the concerns and anxieties of 1950s Harlemites about not having straight hair, about having skin that was deemed too dark, about living in apartments that are lice-infested and underheated, about trudging home after work with feet sore from long hours of laboring as janitors, porters, house cleaners, cooks and dishwashers.

We learn more about that one passing pharmacy window than we ever do about Grave Digger Jones and Coffin Ed Johnson, the two hard-knuckled, trigger-happy detectives who ostensibly are the central figures of the series. In the six Himes novels I have read so far, we never see these two police officers at home. They reside elsewhere, in Astoria, Queens, across the rushing East River, in places we never see. Their families almost don’t exist, except for Ed Johnson’s daughter anomalously appearing as a hostage in The Real Cool Killers. It is telling, I think, that Coffin Ed kills her tormentor in an unusually implausible scene in which he hangs suspended upside-down outside the window of an apartment building.

When the two men do come into Harlem, they are depicted as little more than rumpled mohair suits with heavy pistols bulging in their shoulder holsters under their left breast pockets. It is in Harlem USA that Grave Digger Jones and Coffin Ed Johnson spring to life, often brutally. In A Rage in Harlem, when a man named Gus takes a swing at them, they show what they consider mercy by refraining from shooting him. Instead, they slap him hard, again and again:

Gus’s tight-fitting hat sailed off and he spun toward Grave Digger, who slapped him on the other cheek and spun him back toward Coffin Ed. They slapped him fast, from one to another, like batting a ping-pong ball. . . . They slapped him until he fell to his knees, deaf to the world.

In a scene in a Harlem gay bar in Real Cool Killers, Grave Digger threatens to use his pistol to knock out the teeth of a woman he is questioning.

“That’s putting it on rather thick,” a “blond white man” at the bar comments.

“I’m just a cop,” Grave Digger responds angrily. “If you white people insist on coming up to Harlem where you force colored people to live in vice-and-crime-ridden slums, it’s my job to see that you are safe.”

They also are exceedingly cool customers. When a crazed minister fires a shotgun at Grave Digger through a closed door, the detective drily responds, “You didn’t get me. Try the other barrel.”

By contrast, Himes lavishes entire paragraphs on Harlem. Here’s one twilight scene:

It was a street of paradox: unwed young mothers, suckling their infants, living on a prayer; fat black racketeers coasting past in big bright-colored convertibles with their sold gold babes, carrying huge sums of money on their person; hard-working men, holding up the buildings with their shoulders, talking in loud voices up there in Harlem where the white bosses couldn’t hear them; teenage gangsters grouping for a gang fight, smoking marijuana weed to get up their courage; everybody escaping the hotbox rooms they live in, seeking respite in a street made hotter by the automobile exhaust and the heat released by the concrete walls and walks.

Usually the first time I read a book, I stay focused on the plot. All I want to know is what is going to happen. But the first time I read this passage, I stopped and read it over twice more. I especially like the two kinds of babes subtly contrasted in the first three lines. The lush detail feels to me a bit like Mark Twain’s Life on the Mississippi. He isn’t saying it is good, he isn’t saying it is bad, he is just saying this is what he saw, and depicting it as best he can. It is life. As I have written elsewhere, Himes reminds me a lot of Twain.

So while I agree with the thoughtful Bruce Riordan that Himes is a masterly writer, I think that the real spotlight is on a neighborhood, not the two detectives who police it.

That’s not a bad thing. If, as Albert Murray and James Baldwin asserted, Black culture is at the heart of the American experience, then I think twentieth century Harlem is at the heart of Black culture, or at least was at the time Himes was writing. And I think he captured it beautifully, taking us into the heart of the heart of this country.

***