“We’ve traced the call, it’s coming from inside the house.”

Has ever a line been more chilling? Coming towards the end of twenty-plus minutes of excruciating suspense at the opening to the 1979 movie WHEN A STRANGER CALLS, this classic piece of dialogue, delivered over the phone by a police officer to babysitter Jill Johnson, crystallises one of our most basic fears: there’s a stranger in your home and you didn’t know they were there. It’s a recurring anxiety that has been played on in any number of home invasion thrillers, from my personal favourite example of the genre, David Fincher’s PANIC ROOM (2002), to more standard late-night popcorn fare.

But what happens when we do know the stranger is there? More to the point, what does it mean when we ourselves have invited the danger into our homes?

Our homes are our safe spaces. We have locks on our doors and windows. Some of us set intruder alarms when we go out or review surveillance cameras when we return. In theory, nobody can come in without our say-so. But isn’t it somehow worse to think that we might make a mistake? I would argue that fear and paranoia become much more insidious when we realise, too late, that we are the ones to blame for the peril we find ourselves in. There’s an extra piquancy to that climatic moment of terror when it’s tinged with self-regret and the awareness that we are the architects of our own doom.

Famously, one of the limitations on the power of Bram Stoker’s Count Dracula is that he is unable to enter a place until he is invited in. Imagine being the homeowner to make that mistake. But it’s an error that’s repeated in AN INSPECTOR CALLS, J.B. Priestley’s classic, and oft-adapted, morality play. Once the wealthy Birling family allow a man calling himself Inspector Goole into their home after dinner, he systematically dismantles the deceit and fictions the family have been engaged in, triggering each member of the family to confess and confront their responsibility for the death of a young woman named Eva Smith.

For a more modern spin on the narrative, Rumaan Alam’s LEAVE THE WORLD BEHIND sees Amanda and Clay set out from New York City to rent an isolated holiday home in Long Island with their teenage son and daughter, only for a late night knock on the door to interrupt their holiday idyll. Ruth and G.H., an older couple who claim to be the owners of the home, are seeking refuge from an ominous city-wide power outage, but can they be trusted? Once Amanda and Clay invite them in, an eery atmosphere builds, the slow dread spiked with issues of race and class.

Of course, the decision to invite danger in can be more, shall we say, impulsive. For wannabe novelist Cal Cunningham in John Colapinto’s ABOUT THE AUTHOR, Cal’s potential downfall is set in motion when he returns home to his shared Washington Heights apartment for a drunken one-night stand with the unpredictable Les. Come the morning, Les is gone, but so too is a laptop belonging to Cal’s flatmate, Stewart, a detail which becomes key to Cal’s latent predicament when Stewart later dies in a biking accident and Cal claims Stewart’s unpublished (and brilliant) novel as his own.

Similarly, in Catherine Ryan Howard’s 56 DAYS, Ciara and Oliver, who have only recently met, make the impetuous decision to move into Oliver’s apartment together in Dublin ahead of a Covid lockdown. From the beginning of the novel, we know that 56 days later the police have discovered a decomposing body in Oliver’s apartment, but whose body is it, and what exactly unfolded between Ciara and Oliver in the privacy of their apartment?

Then there are the times when a guest isn’t so much invited in, as there by necessity. In Laura Lippman’s DREAM GIRL — itself a clever inversion of Stephen King’s MISERY — famous novelist Gerry Andersen finds himself bed-bound after a nasty fall in his Baltimore penthouse apartment. In need of care, and swimming in a pain-med drug haze, Gerry becomes utterly reliant on his assistant, Victoria, and night nurse, Aileen. But as strange things happen, and ghosts from the past haunt Gerry’s (waking?) dreams, he finds himself trapped and vulnerable.

Lippman has a neat take in the opening of DREAM GIRL on the perils and peculiarities of Baltimore real estate listings, and the world of real estate becomes a source of danger for Melanie Griffith and Matthew Modine in the 1990 movie PACIFIC HEIGHTS when Griffith’s Patty Palmer and Modine’s Drake Goodman are hoodwinked into renting a first floor apartment in their San Francisco home to Carter Hayes, played by Michael Keaton in menacing form. As Hayes locks himself in the apartment and begins to act peculiarly, Patty and Drake realise too-late that Hayes is a fox in the henhouse hell-bent on disrupting their home and destroying their lives.

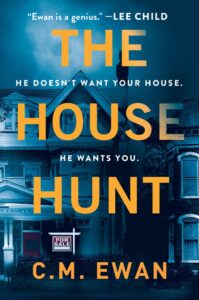

My own novel, THE HOUSE HUNT, also digs into the perils of real estate. Young couple Lucy and Sam have spent two years renovating their beautiful Victorian home in London, but spiralling debts are forcing them to sell, and when their estate agent calls to say that she is running late for a viewing, Lucy, who is home alone, reluctantly agrees to show a potential buyer around. The doorbell rings and Lucy opens her door to Donovan, who is handsome and charming, but soon after Lucy invites him in, Donovan’s unusual behaviour triggers her anxieties. When Lucy asks Donovan to leave, he refuses, leaving Lucy in breathless fear and reliant on her own will to survive.

Where did the idea behind THE HOUSE HUNT come from? In part I was thinking, as I often do in my thrillers, about those everyday situations we put ourselves in that can turn unexpectedly deadly. But I was also remembering a real-life encounter of my own, from when my wife and I were house hunting a little over a decade ago. We arrived at a property we had arranged to view, only for the homeowner to refuse to leave and insist that he, and not the estate agent, should conduct our viewing. Alone with this stranger as we toured the rooms of his home, he began to tell us that he didn’t want to sell, that his wife had cheated on him and was pushing for a divorce, that he would do anything to keep his house.

Suffice it to say, we didn’t make an offer. In fact, we left in a bit of a hurry. But the experience lingered, and years later I flipped it, having Lucy invite a stranger into her home in hopes of selling it, little realising that Donovan doesn’t want her house at all –– he wants her. In Lucy’s desperate need to sell and her crippling desire to please, she doesn’t spot the danger until it is already inside the walls of her home with her. Alas, if only she had heeded the lesson of Count Dracula, and kept her door firmly closed.

***