All good things come in moderation. There is evil in excess.

Surrealism is one of my favorite modes of artistic expression, but it’s no different than anything else; too much of it is gross. A book that’s overladen with surreal elements stops being surreal and starts being weird for the sake of weird. Some people dig that kind of thing, but it’s an extremely niche proclivity. To me, the best examples of surrealism come in the form of works where the weirdness exists closer to the reader’s periphery. Good literature is about the filtering of experiences through a unique consciousness. Sprinkle too much freaky-deaky stuff in there, and it starts getting away from art’s ultimate throughline: the human condition.

My latest novel, American Narcissus, has plenty of strange and surreal elements, but it is a story that is inherently grounded in reality. I wrote it for the same reason I write all of my novels: to work through suffering. Suffering lends a surreal tinge to our perception of events, and that is something I always strive to reflect in my work, but I never want it to get in the way of whatever truths I’m trying to grasp as I grapple in the darkness with what it means to be a person who experiences pain.

The following list is composed of novels which accomplish this in spades. No matter what forms of surrealism they weave into their narratives, the human element is always at the forefront. Each of them exposes some vital, incontrovertible aspect of existence, and whatever weirdness may be present only serves to accentuate that.

Super-Cannes by J.G. Ballard

Ballard is one of my foremost influences and you can’t go wrong with any of his works, but Super-Cannes is an excellent entry point. The drama is centered around a noirish conspiracy amid an upscale suburban enclave of high-powered professionals in the idyllic hills of the French Riviera. A looming dread builds to a breathless crescendo as the reader becomes increasingly aware of how off everything is. Having grown up in sprawling houses with manicured lawns studded along Cheever-esque cul-de-sacs, I’m uncomfortably familiar with the unspeakable darkness that often bubbles just beneath the surface of Stepford families’ gleaming veneers. Ballard captures this with his impeccably cold precision, and his depiction of the gloomy, dreamlike haze that hovers over the sundrenched homes of the haute bourgeoisie is paralyzing.

Eileen by Ottessa Moshfegh

Perhaps the most striking aspect of Ottessa Moshfegh’s work is her ability to craft weird, neurotic, and largely unlikable protagonists who feel intimately relatable. There’s often a sense when reading her novels that she has somehow manufactured a horrifying reflection of all the aspects of humanity that we thought no one knew about us. It’s the “she is just like me for real” effect. The narrator of Eileen is by and large an absolute freak, but there’s something so universal about the depiction of her consciousness that she could be anyone. This creates a haunting and extremely tense mood of anxiety and restlessness that permeates throughout the entire novel. There’s also a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it detail toward the end of the book that seemingly calls into question everything before it, or at least it did for me. I asked Ottessa about it the first time I met her, desperate to know I hadn’t imagined it. She stared at me blankly for a few moments and then said, “I have no idea what you’re talking about.”

The Woman in the Dunes by Kobo Abe

“One must imagine Sisyphus happy,” Albert Camus said. If American Narcissus is a grim nightmare about people unable to find contentment in the Sisyphean struggles imposed on them by both American society and their own self-involved hang-ups and delusions, then The Woman in the Dunes is its mythical inverse. The story of a schoolteacher’s gradual acceptance of his surreal and interminable circumstances isn’t necessarily a happy one (who has time for happy books, anyway?), but there’s something almost aspirational about it. All my life, I’ve envied people who somehow find contentment with the status quo of the bastardized and abridged version of the American Dream, settling into a rote and by-the-numbers existence of dull mediocrity and listless, nullified ambition. Most of us, like the novel’s protagonist, are simply collecting water and trying to keep sand out of our house. It takes a rarified resolve to find the freedom and purpose that Jumpei Niki is able to locate in doing so.

Beloved by Toni Morrison

I had written Toni Morrison off as overrated for most of my life. Upon mentioning this to my then-girlfriend earlier this year, she insisted I was incorrect and that I should read Beloved. This book, she swore, would force me to reevaluate my erroneous (and problematic) opinion.

One lonely night in the early aftermath of our breakup about a month later, I plucked Beloved from one of my many stacks of unread books. I was immediately transported. The tragic narrative is replete with poltergeists, fatal visions, exorcisms, and supernatural folklore, but it’s all rooted in a gritty naturalism that makes it feel as authentic and immediate as any straitlaced family saga. Consider this former hater now reformed.

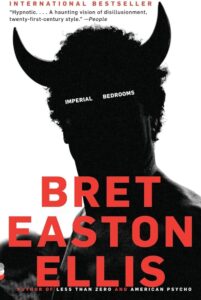

Imperial Bedrooms by Bret Easton Ellis

My all-time favorite novel, and a quintessential work of Los Angeles literature. Serving as a quasi-sequel to Less Than Zero, it sort-of-but-not-exactly retcons the events of the first book in service of delivering a razor-wire tale of obsession gone wrong, told by an alcoholically unhinged protagonist who would make even Patrick Bateman shiver. I’ve never read another book that so accurately encapsulates the toxic lust and romantic delusion that accompany an ill-advised tryst with someone you know from the outset is going to destroy you. There’s also a mystery involving a drug cartel, an underground escort service, a ghost, and (maybe?) vampires, but don’t try to figure it all out. It’s a closed maze. This is not an exit.

***