There are words that we hesitate to use when describing women writers. Nice is certainly one, and approachable might be even more questionable. (Who exactly is approaching, and what are their intentions?) Still, these are the words that inevitably come to mind when I think of the novelist Rebecca Makkai. I met her via email seven years ago, after I randomly sent her a message to ask if she’d written a story I remembered reading in an anthology in the early 2000’s. She hadn’t written that story, but that exchange led to her visiting my fiction class while on tour for her novel The Great Believers, an act of generosity that I still hope my students that semester were sufficiently grateful for.

Like most of the reading public, I adored that novel, which went on to win on the Andrew Carnegie Medal and be shortlisted for the National Book Award and the Pulitzer Prize, and was recently included as one of The New York Times’s 100 Best Books of the Twenty-First Century. However, I felt even more drawn to her next novel, I Have Questions for You, the story of a podcaster drawn in to investigating the decades-old murder of a high school classmate at her New England boarding school. It is, among other things, one of the great literary mysteries.

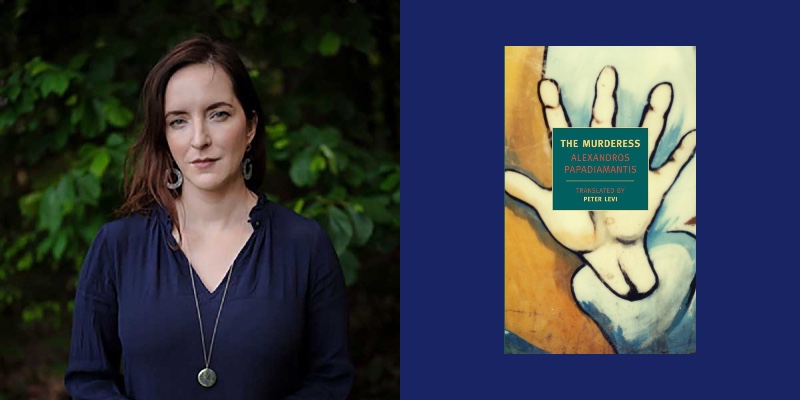

Recently I had the chance to talk to Rebecca about Alexandros Papadiamantis’s novel The Murderess, translated by Peter Levi, which she’d included as one of the selections in her Around the World in 84 Books project. (More on that below.) The plot of The Murderess revolves around the superfluity of girls and women in a poverty-stricken rural community in early twentieth-century Greece. In this environment, parents are expected to marry their daughters young and to give their new husbands extravagant dowries. Given these circumstances, the birth of a girl is looked upon as a tragedy, particularly to the main character, Hadoula, who comes up with her own dark solution to this societal problem.

Why did you choose The Murderess by Alexandros Papadiamantis?

I’ve been doing this project for the last year or so where I’m reading my way around the world in translation. It’s largely a memorial to my father, who was a literary translator among other things, but it also started because I realized that I was reading nothing except contemporary American fiction. I started in Hungary, and I’m going to end in Hungary, but I’m skipping countries like Italy, for example, since Italian literature in translation is widely available and I’ve already read a lot of it. I was making my way through southeastern Europe, and I realized that with Greece, I’d read a lot of ancient Greek literature, but absolutely nothing contemporary. Sometimes I ask people who are experts in the literature of that particular country what I should be reading, but here I just Googled modern Greek novels. This one sounded so weird and juicy, and I could tell it definitely wasn’t going to be dry. I also liked the suggestion of a folkloric element within the literary premise.

Then in terms of picking it for this series, that’s a different question. My last novel, I Have Some Questions for You, is a murder mystery in a sense. When I was writing it, I was reading a good deal of literary crime fiction, including a lot of Tana French, but that was a while ago. I looked back through the list of what I’d been reading lately, and this one jumped out at me. It’s called The Murderess, so it seemed perfect.

When I think of the work I’ve read in translation, I’m realizing now that most of it is in French, Italian, or Spanish. Does it seem that Greek fiction less likely to be translated into English?

I’ve learned that we go through trends in translation. French tends to get translated a lot, but there’s also a lot of Scandinavian literature in translation. I think it began with a few key works like The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, as well as a few literary novels that did really well, and suddenly publishers were saying, “Wait, what else is there from Scandinavia?” And then there are countries and languages from which there’s very little translated literature. It might be partly a matter of finding qualified translators—usually people are translating into their own language, so you’d need someone whose native language is English but knows that other language well enough to translate out of it. I’m not suggesting that Greek is obscure, but it may be a matter of publishing trends, or of the number of people actively working as translators from modern Greek.

I always feel like I should be reading more modern literature from outside the U.S. and the UK, and when I saw on social media that you’d started this project, I thought, “I’m going to keep up with this and read every single one.” I’m embarrassed to say that this is the first one I’ve gotten to, though.

I have people reading with me, but I don’t think anyone’s reading all of them. At some point I’ll probably go back and assemble all of them in one place, but the main thing right now is that I’m writing about them on my Substack.

In your post on Substack, you say that you see social commentary in this novel. Did you see the novel as critiquing the way women are viewed in this community?

There’s definitely a lot to say about both gender and money in this novel. If you think about a writer like Ibsen with A Doll’s House, or Flaubert with Madame Bovary, men sometimes have really interesting things to say about gender, and I’d say that Papadiamantis fits in that category. With Hadoula, it’s like she’s taking the gender constraints and financial constraints of life on this island and taking them to their most ridiculous logical conclusion. Like, “Well, this baby is expensive, so we might as well just kill it.” There’s a little bit of a Modest Proposal vibe there. We’re not meant to agree with her, of course, but she’s also not coming out of nowhere. The dowry system inherently suggests that different lives are worth different amounts, so she’s taking the social realities of Greek culture at this time and saying, “Oh, so this is the way things are. Then I’ll kill people.” There’s an element of satire, and satire doesn’t have to be funny. Satire can be like, “Let’s play this out and take it to the logical extreme.” And there’s also an element of fairytale here, or folklore.

That was one thing I struggled with as I was reading this. I couldn’t quite get a handle on whether I was reading a social critique or a fairytale, but what I hear you saying is that they’re layered on top of each other.

Yes, but I’d say that’s true of fairytales in general. If you look at “Little Red Riding Hood,” there’s clearly a message there about staying away from deceptive men. It doesn’t mean there’s some deep hidden meaning in every story necessarily, but there are reasons that these stories got retold and passed down. With “Cinderella,” you could say it’s about sticking things out, you’ll get what you deserve in the end. I’d say that The Murderess is definitely more pointed than that, but I feel like it has its roots in Baba Yaga stories.

The main character doesn’t just murder once; in our modern parlance, she’d be a serial killer. Do you feel like we have enough psychological insight into the character to understand how she feels about the murders, or is that kind of psychologizing foreign to Papadiamantis’s style?

We’re in her head, and we’re aware of the way she justifies the murders to herself, but at the same time, we’re outside of her thinking, “Oh my God, what are you doing?” I think literature through the twentieth century and into the twenty-first has gotten so close to the character, whether it’s first person or just a really close third. It’s rarer and rarer to have an omniscient narrator or an external narrator who has distance, so I’m always so thrilled when I find it.

Through that move to closer points of view, I think that readers got acclimated to the idea of relating to a main character and walking in their shoes in a way. People started thinking that they wanted for a character what they wanted for themselves, including the morality that they would have for themselves, and they wanted the character to be redeemed at the end and to become a better person. That can be great, but it’s not the only way to tell a story. In this case, we’re put in the head of someone we fundamentally disagree with, and we’re thinking, “No, don’t do that. Don’t kill those children. Oh my God, stop.” It’s a technique that readers today are increasingly uncomfortable with, and they’re especially uncomfortable with female characters who don’t behave and may not even regret their bad choices in the end.

As authors, we’re thinking, “Well, it’s not actually very interesting to read about perfectly virtuous characters, because it’s going to be someone very passive and the story is going to be pretty boring.” But I can’t count the number of times that someone has come up to me after a reading and said, “I love your book, but I have to tell you, this character wasn’t always easy to like,” as if they’re breaking it to me for the first time. I lived with this character for six years; believe me, I know she’s not easy to like. Right now I’m writing about a historical figure who was genuinely a pretty terrible person, and I feel like it’s going to be this social experiment. Maybe it will be easier for people to tell that I’m intentionally making them uncomfortable, intentionally putting them in the head of someone they disagree with, just as Papadiamantis does here.

I found it particularly poignant to read this story in the context of current attacks on reproductive rights. What resonance do you think the novel has for a contemporary audience?

When we read stories from the past of women making desperate, horrifying choices, they’re usually responding to a society in which women had far fewer rights than they do today. We didn’t have no-fault divorce, we had little access to birth control, we could not leave an abusive husband, could not choose not to have children, could not cut ties with terrible parents, etc. We see stories coming out of those societies of women murdering people, dying by suicide, turning to witchcraft, and it’s certainly not a coincidence. Some people have come up with this idea that when women stayed home, everyone was so happy, and they had all these kids and everyone was playing in the back yard having a great time. But look what they were writing. The subconscious of a society is in the literature, and even in the literature from the men, it’s telling us, “Oh no, she’s drinking the cyanide. She’s jumping in front of the train. She’s murdering the babies.” They weren’t happy.

In these interviews, I often end up talking to writers about the distinction between literary and genre fiction. I wouldn’t call I Have Some Questions for You crime fiction, but it employs some of the tropes of the genre in a literary way. What made you want to go in that direction with your work? How would you define the distinction between literary and crime fiction (or is it just a question of marketing)?

When I look back at my books, most of them have crimes in them. The first one is about a kidnapping, and the second one has identity theft, and I Have Some Questions for You is definitely written in the form of a murder mystery. At the same time, I wasn’t that interested in mystery as a genre. I’m not looking down my nose at it when I say that, but it just wasn’t what I was doing. Murder is a thing that happens in real life, and I wanted to consider the questions we would consider in real life: How do we reconstruct the past? How well do we really know the people we think we know? If someone is convicted of a crime, is that really the end of the story? I understood that I was entering into this space, with the expectations that people have for a murder mystery or crime fiction. I had to ask myself, “Am I rebelling completely against those expectations, or am I playing along and subverting them in some way?” One thing I decided is that I did want readers to have a solution to the central mystery by the end of the book. That doesn’t mean justice is served necessarily, but if you start out not knowing who did it, you’re going to end being able to answer that question. I think if I’d really wanted to rebel against genre, I would have ended without a solution. But I did want that arc, from uncertainty to knowledge. At the same time, I wanted to lead with character rather than leading from the framework of genre.

Because it’s not my first book, it’s not getting shelved with mystery in most bookstores. If it were my first book, I think it would be in that section. And I love it when I hear that when someone comes into a bookstore and says, “I want a literary mystery,” that booksellers sometimes think of my book. Sometimes I’ll see posts that say, “If you like Donna Tartt’s The Secret History, you’ll like I Have Some Questions for You,” and I’m always really flattered, even though I think they have next to nothing in common. They’re both campus novels, I guess.

They’re both set in New England and have a lot of snow.

Good point. Snow and death.

I do see what you’re saying about separating the conventional form of the mystery or thriller from the subject matter. We’ve come to associate thrillers in particular with a three-act structure, but there’s no real connection between the subject of crime and these conventions that have grown up around it.

There are certain genres that are never going to relate to real life. Like a vampire story, or a zombie story—chances are good that you’re not going to interact with a vampire or a zombie. But if you think about a love story, most of us are going to experience a real-life love story at some point, or more than one. The romance novel is also a genre, but the two things aren’t necessarily connected. You can write a realist novel that contains a love story, but doesn’t follow the conventions or the beats that people expect from the romance genre. Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s love stories aren’t going to be shelved next to Emily Henry. Murder is similar—a genre has grown up around the subject, but it’s also a thing that happens in real life. If you start to write a vampire story, you’re necessarily entering this genre that precedes you, because you didn’t invent vampires. But with romance and crime, we’re in a different category, because it’s always going to be somewhere between real life and genre.

When you read literature in translation, do you find that non-U.S. authors deal with these questions differently, or feel less indebted to convention?

I’m seeing fascinating differences in writing mode that are really challenging things that I took for granted. I’m reading my way through northeast Africa right now, so it’s Arabic literature in translation, and I’m seeing much less of a reliance on scenes as building blocks, and much more freedom with summary and exposition. With students, I’ll often talk about scenes being the brick and exposition being the mortar around them. Every author is going to have a different balance there, but it’s hard to build scenes out of mortar. But I’ve had to reconsider that view when I read these books that are mostly exposition with a few summarized scenes.

Is there anything you learned from this novel that you might apply to your own work, either in regard to structure or anything else?

I think so. I’ve written a few short stories recently that feel a bit more like folklore or fairytale. I’ve been thinking of them almost like bedtime stories for grownups, and it makes me feel so much freer with summary and jumping around in time. It doesn’t have to be like, “‘Blah, blah, blah,’ he said and sipped his coffee and put it down on the table and forked another bite of pie.” Every time I read something that exists in a bit of a different reality, it pushes me a little away from those expectations. In The Murderess, nothing happens that isn’t feasible in the real world, but we’re skipping all the boring parts. There’s no interstitial backstory or anything like that. It’s just like, “Here she is, and this is what she’s doing.” And there’s something really delightful about that.

I assumed that the novel would skate over the deaths, but it doesn’t: we see the babies that Hadoula murders being strangled and the older girls being drowned in some detail. Why do you think Papadiamantis lingers over those moments, and why doesn’t it come off as exploitative or unnecessary (if you agree that it doesn’t)?

I think it’s partly because of the fairytale thing. Again, when we hear “Little Red Riding Hood” for the first time, we don’t react the way we would if we heard about a real wolf eating a real grandma. You know you’re in this slightly magical world where bad things might happen, and that creates a certain distance.

How have the people who are reading along with the 84 Books project responding to it?

It’s been really cool. Usually I’m the person who hears about the winner of this year’s Nobel Prize and I say, “Who’s that?” But I want to change that about myself, and I’m glad that I’ve been able to contribute in a small way to a broader awareness of global literature. Sometimes I’ll post about a novel and then I’ll hear from people who say, “That sounds so good, I just ordered it.” At book events, I get asked pretty frequently what I’m reading, and my recommendations have usually been these books in translation, and then people tell me they’re going to order this Turkish novel they’d never heard of before. I love being able to spread the word in that way.

One of the books that I read last summer was this Palestinian novella by Adania Shibli, and then in October she got uninvited to the Frankfurt Book Fair. She was going to receive a prize, and then they decided it was too controversial to give it to a Palestinian author. Then I got a lot of messages from people saying, “I read this book because of your series, but I wouldn’t have even heard about it otherwise.” I think it’s good that a few more people know enough to say, “This was a bad decision, they should not have uninvited this author.” It’s a really important and beautiful book.

And it’s not just writers who should be reading more broadly. I think it’s good for citizens in general, because as Americans we tend to think in such an insular way. The more aware we can have of what’s going on in the world, and of other literary traditions, the better.