Part One: The Passion of Aline and Henry—

A True Tale of the Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous between the Two World Wars

The headline was horrific. “Wife, Beaten for 6 Years, Can’t Take It Anymore,” blared the title to the story about Aline (Stumer) von Rhau’s divorce suit against her husband, Henry von Rhau, in the New York Daily News on April 27, 1933. Before a Bridgeport, Connecticut courtroom packed with “society folk,” the Daily News reported, “the wealthy and socially prominent Aline Stumer von Rhau” testified before Superior Court judge Arthur F. Ells that the “six years of her married life were marked by one long series of beatings, featured by an occasion when her husband devoted an hour and a half to punching and kicking her.” The “stunning brunette” and “attractive brunette society woman” pleaded for a divorce from her “tall, dashing husband, Major Henry von Rhau, United States Army, retired, now a novelist and actor,” on the grounds of intolerable cruelty. The Daily News’ readership, no doubt itself resoundingly virtuous, could hardly have asked for better confirmation of the decadence and folly of the loose-living transatlantic rich.

Aline Stumer, Passport Photo Aged 18

Aline Stumer, Passport Photo Aged 18

Once the story got into the nasty nuts and bolts of the case, things did not seem to get any better for Henry von Rhau’s cause. Testifying in support of Aline were her friends Mary Messmore, daughter of famed New York society art dealer Carman H. Messmore, and Katherine Fiske, daughter of the late Haley Fiske, president of the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company. Miss Messmore told of being on a visit to the couple’s summer estate at Fairfield, Connecticut when she saw the Major stride into the house, elegantly clad in his riding habit, and proceed to viciously kick Aline.

Henry was just as unpleasant to his wife when in the City, according to the testimony of Miss Fiske, which was briefly quoted in the Daily News. “I was sitting with Mrs. von Rhau in her apartment at 955 Park Avenue one afternoon playing backgammon when Major von Rhau came in,” she related. “‘Haven’t you two got anything to do but play backgammon all the time?’ he demanded.” Thereupon, she claimed, von Rhau punched Aline in the jaw and ordered her, Miss Fiske, out of the apartment. Another newspaper account, in the Scranton Times Tribune, rather less formally quotes Miss Fiske’s testimony on this point as follows: “He cried: ‘You lousy so-and-so, haven’t you two got anything to do but play backgammon all afternoon? And he punched her on the jaw and said to get out of there.”

Details of the worst episode in the von Rhaus’ married life together came directly from Aline herself. The stunning brunette contended that Henry had connived with one of his buds, Thomas McHugh, to frame her for infidelity, giving von Rhau an excuse for administering to her the worst beating that she ever received from his hands. According to Aline, on the night in question she had been on her way to have dinner with her gay best friend Claude Kendall, publisher of the first book written by her husband (and the two novels of Kendall’s and von Rhau’s wealthy dilettante mystery writing pal Willoughby Sharp), when she received a phone call from McHugh inviting them to have cocktails at his apartment before dinner.

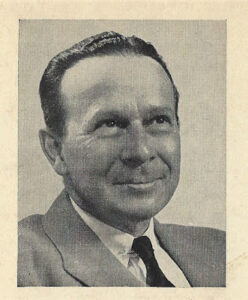

Henry von Rhau

Henry von Rhau

At McHugh’s place it was not long before Claude Kendall, who by the time was suffering from increasing alcohol addiction (a few years later he would be beaten to death in his hotel room by a male pickup), had passed out from imbibing too many cocktails, leaving Aline alone with McHugh, who, she said, suddenly got up and exited the room. No sooner had he departed than von Rhau entered the room and locked the door, announcing fiercely to Aline, “Now, I am going to kill you.” Stripping to his waist, he proceeded, in Aline’s words, “to beat me with his fists and [knock] me around the room for an hour and a half, ripping my clothes.” When McHugh finally returned to the room, leaving the door open behind him, Aline fled for her life, running out of the building and into a taxi. She spent the next month recovering in bed.

To top off this terrible tale of toxic masculinity, Aline added that during their marriage she had essentially “kept” her spouse, supplying Henry with four saddle horses, a valet and a car, paying all the household expenses and advancing him money so he could continue with his writing. “He could never find a publisher,” one newspaper noted, “so finally she organized her own firm and put one of his novels on the market, but she lost money on it.” (Was this Inwood Press, which originally published Henry’s satire of the celebrated lesbian novel The Well of Loneliness, entitled The Hell of Loneliness? Did Aline get a friend, American expat John Mullins, to help finance von Rhau’s coyly pornographic, woodcut illustrated book innocently entitled Tale of the Nineties?)

Rather humiliatingly Aline had even born the cost of her and Henry’s three-week honeymoon trip to Bermuda, even to the extent of picking up the tab for the travel fare of the freeloading Thornton Wallace “Wally” Orr, a “Manhattan clubman and crony of the Major’s,” a newspaper explained, “who made the voyage with them.” According to Aline, her new husband actually had spent most of the honeymoon not in her company, but rather that of jolly Wally Orr, who had been best man at their wedding.

Naturally the defense did not allow Aline’s ghastly parade of horribles to pass by unchallenged. Henry’s attorney demanded of Aline to know why she had married von Rhau when she knew that he was a man of “nervous and irritable” temper, to which Aline invoked the power of a woman’s true love, replying, “I thought if I married him and gave him a good home, which he had never had, it would cure him.” Additionally, several former army associates and friends of von Rhau’s took the stand in his defense, making the case very much of a “boys versus girls” affair. (The newspapers did not quote the men, however, so I do not know whether such pals of Henry’s as Willoughby Sharp, Jack Boissevain, son of the president of the Hilliard Hotel Company, and famed playwright and Henry’s gay best friend John Colton, author of the plays Rain, The Shanghai Gesture and Under Capricorn, took the stand.)

For his part, Henry emphatically denied that he had ever beaten Aline. One newspaper reported that the former bit part actor “presented a picture of abject humility on the stand.” He called himself “the world’s worst husband,” explaining that he was “temperamental because I’m a literary man, selfish and thoughtless.” Yet he insisted that although “my shortcomings as a husband were of the gravest kind….I love her, and I never beat her.”

Henry admitted only to a single physical misdeed with Aline, which took place, he said, at a dinner party they had given, where Aline had twice abandoned their guests to go for a car ride with the same male guest. “On the second occurrence I slapped her. I’m sorry I did.” On another occasion Henry admitted to using force with Aline, but in that instance it was done “to keep her from jumping out of a window.” Von Rhau insisted that he wished to reconcile with his spouse, in part for the sake of their four-year-old son, Anthony, but also because he still loved her. Aline remained “the loveliest girl I have met,” he declared on the stand, bringing tears to his wife’s eyes.

Whether he himself shed any tears, Judge Ells was impressed with von Rhau’s testimony that “his one idea in life was to become reconciled with his wife.” At the conclusion of Henry’s testimony, the judge “summoned the couple to his chambers, excluding even their lawyers, and sought to bring them together.” This attempt was unsuccessful, however, with Aline emerging after thirty minutes with Henry in the judge’s chambers still resolved upon obtaining a divorce. Such was granted a week later, Judge Ells having determined that “intolerable cruelty was proved by a fair preponderance of the evidence.” Yet the judge, in a suggestive comment, also made a point of commending von Rhau’s “chivalry during the trial.” Had “dirt” about Aline been left out of the courtroom?

Perhaps Judge Ells’ heart was gladdened when, just a few weeks after he granted the divorce, Aline and Henry rewed.Perhaps Judge Ells’ heart was gladdened when, just a few weeks after he granted the divorce, Aline and Henry rewed. The next year Aline gave birth to the couple’s second child, a daughter named Cynthia, on November 28. A month later von Rhau hosted a Christmas Eve “cocktail party for intimate friends.” Over the next two years, newspaper society pages were full of accounts of the whirl of activities engaged in by the seemingly happily reunited Mr. and Mrs. von Rhau. In February 1935, the couple departed on an eighteen-day cruise to South America. The next year they left New York for Los Angeles, perhaps with the goal of introducing Henry to Hollywood. Their doings were detailed in newspaper society pages.

In LA the couple was regularly accompanied by Henry’s playwright pal John Colton, in keeping with Henry’s habit of having a stag male friend, straight or gay, tag along with him and Aline. In June Henry and Aline attended a buffet supper dance in costume. Henry was decked out as a Prussian military officer—seemingly his favorite performative role—while Aline, recalling Henry’s bawdy book Tale of the Nineties, came dressed as an 1890s burlesque soubrette. (One imagines the couple enjoyed a lively fantasy life.) John Colton was present as well, though sadly no information was provided about his gay apparel.

Aline and Henry made news as well when they appeared separately at society functions. In August Aline attended a “Bavarian party” (questionable taste, perhaps, in 1936), where famed soprano Rosa Ponselle “sang Strauss waltzes divinely,” and attended a performance of John Colton’s new stage comedy, She Tripped up the Queen. In September Henry along with John Colton attended a dinner party given by screenwriter and composer Sam Hoffenstein and his wife Edith in honor of Chester Alan Arthur III (aka Gavin Arthur), grandson of the American president of the same name and a future pioneering gay rights activist. Other guests included author Anita Loos and her husband, director John Emerson; actor Fredric March and his wife, actress Florence Eldridge; and pianist Alex Steinert, who during the “wee small hours” played the entire score of Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess, along with his own arrangements of pieces by the Russian composers Rimsky-Korsakoff and Borodin.

It was for relaxation from this hectic social whirl that Aline and Henry, with John Colton in tow, went to a California dude ranch, the Rancho Verde, in October, a chatty LA Times society column informed its readers:

While “Hank” was busily learning to become a cowpuncher by chasing…steers around and around, John relaxed on the front porch of his cottage with his feet in the sun and head in the shade and a flit gun in his hand. Oh, for a camera!

Aline got aboard a horse for the first time in ten years and isn’t sitting down with any comfort yet. And it all comes under the head of fun—which as a matter of fact it really is.

The fun was all over by December, when, five days after Christmas, Aline again filed for a divorce from Henry, accusing her husband for a second time of intolerable cruelty and asking for custody of their two children, eight-year-old Anthony and two-year-old Cynthia. This time no details of the divorce suit were published in the newspapers, but Aline’s suit had been granted seven weeks later, in February 1937, when French Riviera habitue John Edward Mullins, who it will be recalled had underwritten (at Aline’s behest?) Henry’s book Tale of the Nineties, was divorced at Grasse by his wife, Silvia Marietta Jose, on grounds of desertion. Immediately after the divorce, Mullins announced his engagement to Aline Stumer, formerly von Rhau. Mullins planned to depart from Marseilles aboard the steamship Excalibur, his destination being Beverly Hills and Aline. In the event, however, Mullins wed, on April 26 in Manhattan, not Aline, but one Gladys Celene Carroll, a former Woolworth’s sales clerk. Two months later he died aboard the Italian ocean liner Rex, the diagnosed cause being “delirium tremens, with hepato-cardiac insufficiency”—meaning, I assume, that chronic long-term alcohol abuse on Mullins’ part had led to fatal heart failure.

Sadly, the perils of Aline would continue over the next dozen years, much to the enjoyment of the newspapers, which liked nothing better—with the exception of murders of course—than lurid tales of erratic heiresses. In 1938, while residing in LA at 7959 Hollywood Boulevard, Aline was arrested with her twenty-two-year-old brother Louis on suspicion of drunk driving and embarrassingly booked at the county jail, where she gave her name as Mrs. Aline von Rhau—von Rhau, to be sure, having more aristocratic jailhouse cachet than Stumer.

Eugenio Casagrande

Eugenio Casagrande

Meanwhile multiple-handled Aline’s mother Blanche Regina (Griesheimer) Stumer Giddens did her part to keep the Stumer clan in unfavorable headlines. In 1938, having divorced her second husband, Blanche at age fifty-five married forty-six-year-old Count Eugenio Casagrande, an Italian Great War hero, celebrated aviator and naturalized American citizen who not long after Pearl Harbor was detained as a dangerous enemy alien by FBI agents at an internment camp at Ellis Island. Casagrande, “a darling of the Park Avenue circles” who before his arrest had been general secretary of the Unione Italiana di America, a federation of three hundred Italian and Italian-American societies, was characterized by the ever-informative New York Daily News as “an original Fascist.” Blanche—or, as she was now known, Countess Casagrande—divorced the Count the next year. The Stumer women seem to have relinquished their own Jewish heritage, by the by. Blanche, for example, altered her hefty surname Grieseheimer to Gresham, as did her daughters, and all three women seem to have had Christian weddings. Doubtless those Park Avenue circles that were so admiring of Eugenio Casagrande would not have had it any other way.

Although apparently politically anodyne, at least, Aline’s matrimonial record in the Forties proved every bit as disastrous as her mother’s, if not more so. Successively she wed and divorced three different men in under a decade, beginning in 1940 with Ernest Irving Rodehau, a salesman and son of German immigrants, continuing with one Walter C. French in 1943 and concluding, most enticingly ingloriously, with Turkish native Orhan Lambiro in 1949.

From the last listed of the spouses, Aline sought a divorce after merely twelve days of marriage, bringing to mind the appellation “Aline of a Dozen Days.” Although with her third and fourth marriages and divorces (after the two with Henry), Aline seems to have avoided adverse notice from the press, the third sequence simply had too many outré elements, by postwar American standards, to let pass unmentioned in the newspapers. At the time he wed forty-five-year-old Aline, Orhan Lambiro was but a fetching lad of twenty-three, working as a lifeguard and “beach boy” at Miami Beach. Initially newspapers reported that Lambiro was the son of Turkish diplomat, but the modest young lifeguard—described, predictably, as “dark” and “husky” by the newspapers—modestly corrected the record.

Speaking to reporters Lambiro explained that he was not the son of the Turkish delegate to the United Nations, his father being merely an employee of the Turkish delegation. Aline, he claimed, had been responsible for the propagation of that particular falsehood: “She didn’t want her fourth husband—me—doing common work, so I suppose she didn’t want my father to be a working man either.” Lambiro added that he had been an American Army staff sergeant during the Second World War, serving overseas in Europe.

Aline had her own complaints about Orhan, however, as she had many years ago concerning Henry. Her latest spouse, she asserted, had pressured her to finance a Miami Beach bookie joint and additionally had, like Henry, mercilessly beaten her. (To be sure, he did have gambling offenses enumerated in an arrest record.) Aline demanded one hundred dollars in weekly alimony from an outraged Lambiro, who attested that as a lifeguard he made but fourteen dollars a week (about one hundred and fifty dollars today).

Lambiro countered with his own tale of marital woe, insisting that Aline had humiliated him by frequenting bars with another man. He also claimed she told him that she had married him “solely for spite.” He asked that the divorce petition be dismissed at Aline’s cost. Certainly Aline’s case was not helped when her attorney called off the alimony hearing upon learning that Aline had an income of seven hundred dollars a week—today about $7500 a week, or $360,000 a year. $360,000 may have seemed like penury to Aline, but it would not have seemed so to most people, and certainly not to the beachcombing Orhan Lambiro.

However it all was finally worked out between Aline and Orhan, the unblissfully wedded couple successfully divorced the next year. Aline, still ever hopeful that the right man was just around the corner, would marry one or two more times before she passed away at the age of seventy in 1975. Henry von Rhau himself married again in 1939, this time happily, although in 1960, eight months after his wife’s death, a despondent von Rhau committed suicide by shooting himself in the temple with a .45 caliber revolver. He had actually enjoyed his greatest literary success in the 1950s with a book called Fraternally Yours, a fictional tale of racketeering and gangsterism which approving critics frequently compared to the writing of Damon Runyon.

Thus concludes this glimpse at the between-the-wars lifestyles of the beautiful, dysfunctional people, which the press so loved to chronicle for its readers. Let us now go back a bit, over half a century, back when a still single Aline in France boarded Le Train Bleu….

Part Two: Hearts of Fire: The Mystery of the Blue Train

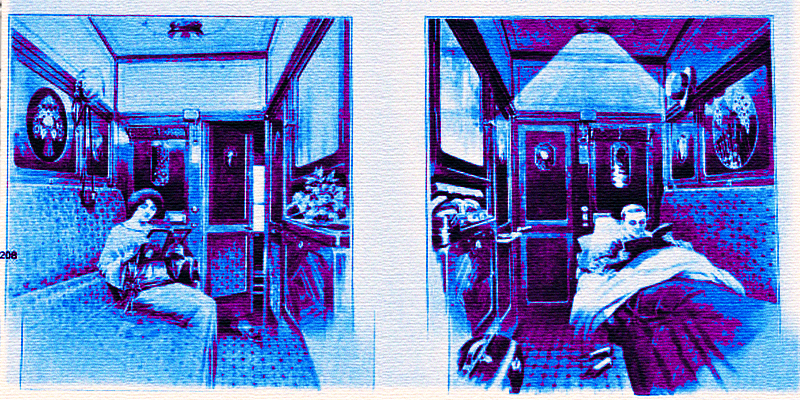

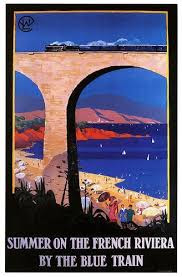

Cannes is 953 miles from London. You travel 850 of those miles—that is, from Calais—in the Mediterranean Express. The Labels with Mediterranean Express printed slantwise on them are pasted on your trunks. You do not, however, call it the Mediterranean Express. It is the Blue Train.

At Cannes you never meet anyone who has not arrived on the Blue Train. That is the sole train to arrive by. Hosts of visitors arrive, in fact, by other trains. They do not mention this shameful secret. Such is human nature. The Blue Train, you see, is a little faster than rival trains. That is something. It is also more expensive. That is everything.

Otherwise, the one positive difference between a sleeping car in the Mediterranean Express and a sleeping car in the rapide is that the latter is painted brown outside and the former is painted blue.

To paint the Mediterranean Express blue, I admit was a stroke of genius. It definitely advertises the train wherever it goes. And the passengers staring languidly from its windows are perhaps not unaware that they partake in the splendor of its advertisement.

It is a rich, royal blue, the paint on the outer walls of those sleeping cars. But within the compartments resemble those behind the brown walls of the older sleeping cars. The upholsterer has still persisted in choosing one of the six ugliest colours in the world for his upholstery, which is of the uncanny peacock velvet met with only in wagon-lit rolling stock. The leather paneling still has twirliwigs executed in –apparently–treacle. But when night comes, and you are snug in your berth, you realize that a sleeping car is meant to sleep in, and naught else.

—”The Only Train,” by author and photographer Ward (Wardrop Openshaw) Muir, in the London Daily Mail, 1926

“I want to go to Nice the next week…. What is the best train?”

Well, of course, the best train is what they call the “Blue Train.”

—Katherine Grey plans a journey in The Mystery of the Blue Train

“It is iniquitous!” cried the Count warmly; “the police should do something about these train bandits. Nowadays no one is safe.”

—the Comte de la Roche protests Ruth Kettering’s murder aboard the Blue Train in The Mystery of the Blue Train

“Trains are relentless things, aren’t they, Monsieur Poirot? People get murdered and die, but they go on just the same.”

—Lenox Tamplin laments to Hercule Poirot in The Mystery of the Blue Train

When Henry von Rhau and Aline Blanche Stumer wed at St. James’ Episcopal Church in Manhattan in 1927, newspapers noted that the attractive twenty-three-year-old brunette was the daughter of the late Louis Michael Stumer, one of Chicago’s leading businessmen. A highly successful retail merchant, Louis Stumer had co-founded the colorful trio of popular fiction magazines known as The Red Book, The Blue Book and The Green Book. Henry’s own father, Gustav Rau, had imported wood pulp, while Aline’s father had co-founded pulp fiction magazines. Appropriately Henry would soon be writing, if not pulp fiction, then something resembling it in spirit. Indeed, it might be argued that the life of Aline and Henry von Rhau, as we must now call him, began to resemble fiction, the “von” in his name evidently being spurious, as was Henry’s claim that he was the heir to a German baronetcy, which he had quixotically, if patriotically, eschewed, so he said, all out of his love for America. Or perhaps we should say that fiction, like Agatha Christie’s fifth Hercule Poirot detective novel The Mystery of the Blue Train, began to resemble the lives of Aline and Henry von Rhau.

When Henry von Rhau and Aline Blanche Stumer wed at St. James’ Episcopal Church in Manhattan in 1927, newspapers noted that the attractive twenty-three-year-old brunette was the daughter of the late Louis Michael Stumer, one of Chicago’s leading businessmen. A highly successful retail merchant, Louis Stumer had co-founded the colorful trio of popular fiction magazines known as The Red Book, The Blue Book and The Green Book. Henry’s own father, Gustav Rau, had imported wood pulp, while Aline’s father had co-founded pulp fiction magazines. Appropriately Henry would soon be writing, if not pulp fiction, then something resembling it in spirit. Indeed, it might be argued that the life of Aline and Henry von Rhau, as we must now call him, began to resemble fiction, the “von” in his name evidently being spurious, as was Henry’s claim that he was the heir to a German baronetcy, which he had quixotically, if patriotically, eschewed, so he said, all out of his love for America. Or perhaps we should say that fiction, like Agatha Christie’s fifth Hercule Poirot detective novel The Mystery of the Blue Train, began to resemble the lives of Aline and Henry von Rhau.

A passport application submitted at the American embassy in Paris by Aline Blanche Stumer five years before her marriage to Henry von Rhau in 1922, when she was but eighteen, includes a striking photograph of her, in which she appears as a frizzy-haired brunette with big intense eyes, a Cupid’s bow mouth and a rather woebegone expression. One almost expects to hears the words “I have always depended on the kindness of strangers” issuing from the pretty lips of this particular Blanche.

In an affidavit dated September 1, the young woman, who for the moment was staying in Paris with her mother and sister at the Hotel Ritz, explained that she needed a new passport because a thief had absconded with her previous one. Sounding for all the world like she just stepped out of The Mystery of the Blue Train—a decadent tale of the fiendish murder of an American heiress and the theft of a fabulous ruby (1928)—Aline elaborated:

On August 29, 1922, I was getting out of the Gare de Lyon [railway station], at Paris, France. I had my passport in my jewel case which I was carrying myself, but which I laid for a short moment on top of my hand luggage, and which was stolen during that very short time when I was not actually holding it. I immediately notified the French police but all their efforts failed to trace either my missing jewels or my passport.

It must be admitted up front in assessing The Mystery of the Blue Train, Agatha Christie’s 1928 tale of the brutal termination of a troubled, traveling American heiress and the theft of her precious ruby, that the Queen of Crime resoundingly hated the book. Indeed, she bluntly stated just that, “I hate it,” adding categorically that The Blue Train was “Easily the worst book I ever wrote.” Just so people would be sure to get the idea, she also avowed:

I have always hated The Mystery of the Blue Train. Presumably I turned out a fairly decent piece of work, since some people say it is their favorite book (and if they say so they always go down in my estimation). It was terribly full of clichés, the plot was predictable, the people were unreal.

Reflecting how miserable she was during the composition of The Mystery of the Blue Train—it was the lowest time of her life, when she was in the process of divorcing her unfaithful husband, Archie—the Queen of Crime elaborated that the novel had neither “zest” nor the “faintest flash of enjoyment about it.” In his book on Hercule Poirot, author Mark Aldridge defends The Blue Train from Christie’s own disses as simply a “slightly lesser Poirot mystery,” yet he deems that the book is marred by “padding,” “extraneous characters,” “narrative dead-ends” and “disorienting shifts of focus.” Aldridge concludes that the novel “is a relatively rare Christie that is only really satisfying on its first reading.” I have something of a different view, as my second reading of the book was much more satisfying than my first—although I must admit that over four decades separated the two readings. I first perused the novel when I was a guileless pre-teen, ill-equipped by worldly experience to judge the book’s strengths.

Agatha and Archie

Agatha and Archie

Perusing Aldridge’s book, it strikes me that the author is one of those rare cases of a Christie academic who really values Christie because of—not in spite of—her superb puzzle plotting. I would agree with him that The Blue Train is not Christie’s most meticulous puzzle plot (it was expanded from a clever, but quite short, story, “The Plymouth Express”); yet the digressions and “padding” and “extraneous” characters which he dislikes contrarily add a lot of appeal to the book as a novel in my view. Contra Christie too, I think many of the characters are of real interest. Among Christie’s great output of mystery fiction The Blue Train arguably is the book in which she best explored the decadence, dissipation, dysfunction and dissatisfaction of the between-the-wars gilded set—people like Aline Stumer and Henry von Rhau.

The Blue Train arguably is the book in which she best explored the decadence, dissipation, dysfunction and dissatisfaction of the between-the-wars gilded set…To be sure, the novel gets off to a slow start with two short “exotic” chapters in criminal Pa-ree. I was interested to learn from Mark Aldridge that these two chapters did not appear in the serialization of the novel. I could have done without the two mixed blood characters, Boris Krassnine (“His father had been a Polish Jew”) and Olga Demiroff (who cannot disguise “the broad Mongolian cast of her countenance”), whom we never see again anyway. However, Chapter Two introduces Greek jeweler Demetrius Papapolous and his daughter Zia (who employ a manservant with “gold rings in his ears” and a, yes, “swarthy cast of countenance”), who are interesting characters and show up several times later in the story.

We also are introduced to a rich American—is there any other kind in Golden Age British mysteries—and a mystery man with false white hair, known as Monsieur Le Marquis, not to mention a roving gang of Paris street ruffians known as Apaches. It is all rather confusing and more the sort of thing you would expect to find in an Edgar Wallace thriller, but it settles down for a while in jolly old England in Chapter Three, which introduces to readers in London willful American millionaire Rufus Van Aldin and his Great War veteran secretary, Major Richard Knighton.

We learn that Rufus, presumably a widower, has an equally willful daughter, Ruth, upon whom in Chapter Four he bestows a recently acquired fabulous ruby necklace, the pendant of which is the famed bauble known—most suggestively given the flaming sexual ardor of a number of the characters—as the “Heart of Fire.” (In modern value it is worth up to some 7.5 million dollars, apart from the historical aspect.) Poor Ruth is having her troubles in the love department, so the Heart of Fire will make a nice pick-me-up for her, so her doting papa’s thoughts run. You see, Ruth’s dissolute English husband of a decade, Derek Kettering, an impoverished heir to a title, is playing around with an exotic—I am using that word a lot, aren’t I?—French dancer named Mirelle. (I do not believe that we ever learn her last name—maybe like Prince and Madonna, she does not have one.) Papa Van Aldin advises his precious daughter to get a divorce and tells Derek that he had better not contest the suit or he will break him. He also sets a purposefully featureless private detective, one Mr. Goby, on Derek’s trail.

When Derek takes the news over to Mirelle and she learns that Ruth has not made a will, this mercenary Frenchwoman, a true she-devil, muses over how convenient it would be for them both were something—something nice and fatal—to happen to Ruth….Meanwhile Ruth herself has her own romantic skeleton in the closet in the suave French form of the Comte de la Roche, whom her papa separated her from when she was 18, leading to her marriage to Derek. It seems she has taken up with him again. Oh, those Frenchmen!

All this takes us through Chapter Six. In Chapter Seven we are introduced to an entirely different milieu and another major character, Katherine Grey, a lady’s companion thrown out of work by the recent death of her old lady. She resides in St. Mary Mead (!), a village which certainly will be familiar to readers of Christie’s Miss Marple mysteries. The Queen of Crime started writing her first Miss Marple short stories in 1927, about the same time she was writing The Blue Train. It would have been lovely had some of the Miss Marple characters been mentioned in the novel, but alas not. Still the St. Mary Mead milieu in The Blue Train surely will seem very similar to fans of the Miss Marple mysteries.

To her surprise, Katherine inherits a considerable fortune from her deceased employer and she decides she wants to get out and experience the world for the first time in her life. As a companion she has spent all of her years shadowed in the shade, listening patiently to others talk about themselves, and now she wants actually to get out and do things. Katherine reminds me somewhat of Anne Beddingfield in Christie’s The Man in the Brown Suit (1924), except that I find Katherine much more sympathetic. There is also some resemblance to Jane Grey, the similarly symbolically surnamed female lead character in Death in the Clouds (1935).

Happily for Katherine, she has a cousin, beautiful Viscountess Rosalie Tamplin, who lives on the French Riviera at the Villa Marguerite in Nice; and the viscountess invites Katherine to come visit her at her lovely, exotic (there I go again) home. Although Rosalie has not only a title but some remaining wealth from her three previous husbands, she is always on the lookout for more lucre and she thinks unworldly Katherine might make something of a “touch.” Her latest husband, Charles “Chubby” Evans, is a costly possession seventeen years younger than she with no money of his own. Lady Tamplin also has an adult daughter, Lenox, who is regrettably rather sardonic and hard-bitten and has not yet landed a wealthy husband. Worse yet to Lady Tamplin, Lenox looks older than her years, making Lady Tamplin concomitantly seem older to people who take the time to do the mental arithmetic.

You can see the lack of tightness here, in that we have three distinct sets of characters from separate milieus: the London set, the St. Mary Mead set and the French Riviera set. And don’t forget the Papadolouses, father and daughter, and the mysterious M. Le Marquis, who were introduced earlier in the story. You can see why this mystery is about 90,000 words long, lengthier than most of Christie’s output, I believe. At times it felt like I was a reading a sensation novel, in terms of the wider scope.

Christie clearly was quite bummed out with life when she wrote this book…Christie clearly was quite bummed out with life when she wrote this book, and I think that attitude is reflected in it and actually enhances it. There is a darkness to The Blue Train which is rather refreshingly bracing. Ruth is strangled in her sleeping compartment on the exclusive Calais-Mediterranean Express while traveling to southern France to meet her lover, after she has had an impulsive heart-to-heart chat with Katherine, who is on her way to see her cousin in Nice. While Ruth is no saint, neither does she come across as a natural murderee like so many characters in Golden Age mysteries, an unsympathetic stick figure who was “asking for it,” as it were. She is cruelly and callously done to death. I was unpleasantly reminded, a bit, of the whole Amanda Knox affair.

Another striking thing about this The Blue Train besides its emotional “coldness” is its “hotness”—by which I mean that most of the characters, men and women alike, are quite sexually active people. With a few exceptions, the women are older and experienced, let us say, and have had relationships, perhaps not always wise, with attractive men. Let us not even start on exotic French dancer Mirelle! That she is sexually experienced goes without saying. She is a hellcat.

But there is also Ruth, 28, and her involvement with both Derek and the Comte. There is Pia Papadolous, 33, who had to be extricated from the consequences of an ill-advised teenage fling by old Papa Poirot himself. There is Lady Tamplin, 44, who with her fourth marriage has bought herself a much younger man and alone among these women seems happy. Katherine Grey (like Pia 33—his book has much precision about people’s ages) is of course a former companion who, until recently, had few options in her life and presumably she is a virgin. She very much regrets the adventures and experiences which she has missed in her withdrawn life:

Autumn, yes, it was autumn for her. She who had never known spring or summer, and would never know them now. Something she had lost could never be given to her again. These years of servitude in St. Mary Mead—and all the while life passing by.

Even young Lenox Tamplin—we don’t know her exact age but I am guessing early twenties—is unsatisfied romantically, stuck in her vain mother’s shadow, and she predicts sadly to Poirot: “Journeys end in lovers meeting…. That is not going to be true for me.”

What a melancholy, autumnal tone there is to this novel, set in part in the sun-drenched Rivera! I cannot help thinking it reflects Christie’s views as she headed for Las Palmas in the Canary Islands with her young daughter at the beginning of 1927 to try and recuperate from what surely had been a 1926 nervous breakdown when she was thirty-six (her notorious disappearance) and get to work on another Poirot novel in the wake of her career triumph with The Murder of Roger Ackroyd. “You just can’t trust beautiful men like Archie,” she must have been thinking. “Those youthful romantic flings don’t last; I’m pushing forty, I’ll never find love and happiness again….”

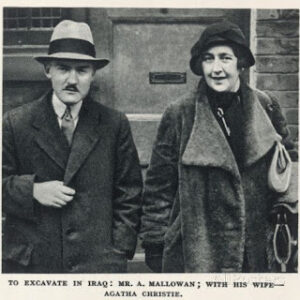

Max and Agatha

Max and Agatha

Agatha did find love and a more stable companionship again, however, with a plain but accomplished archaeologist, Max Mallowan, who was thirteen years younger than herself (shades of Lady Tamplin). She met and married Max in 1930, two years after the publication of The Blue Train, and they remained together as woman and husband until Agatha’s death, at age eighty-five, nearly a half-century later in 1976. With her marriage to Max, Christie picked up the Poirot series again, publishing a remarkable, unbroken string of successes between 1931 and 1942, from Peril at End House to Five Little Pigs. (After that the series slacked off a bit.)

Admittedly, some of the writing in The Mystery of the Blue Train is repetitive and cliched, suggestive of the weary soul who wrote it. The phrase “cast of countenance” is used three times, the first two times within but a few pages of the other. A vase is broken in “a hundred pieces.” One page has rather a, well, surfeit of italicized French lingo. (The late mystery writer Robart Barnard smirked at what he termed the novel’s “plethora of sixth-form schoolgirl French.”) At another point so many characters start coughing—Ruth’s maid, Ada Mason, the French policemen, Mr. Goby, Poirot himself—that I started thinking I was reading one of British mystery writer Patricia Wentworth’s Miss Silver novels. (Miss Silver debuted the same year.)

Yet there is sharp, incisive writing too. “Moral worth, you understand, it is not romantic,” observes Poirot to his Wodehousian manservant, Georges, introduced into the series in this novel, concerning the age-old attraction of women to handsome men with bad reputations, adding sagely: “It is appreciated, however, by widows.” To which Georges with bland ghoulishness responds: “I always heard, sir, that Dr. Crippen was a pleasant-spoken gentleman. And yet he cut up his wife like so much mincemeat.”

St. Mary Mead spinster Amelia Viner is a delight and sounds a great deal like Miss Marple when she speaks of men—excuse me, gentlemen—like they are some strange species apart from the distaff side of the human race: “I have always heard that gentlemen like a nice piece of Stilton [at dinner], and there is a good deal of father’s wine left…. No gentleman is happy unless he drinks something with his meal.”

Poirot himself only pops up about a third of the way into the novel, but he is wonderful, very much the magical “Papa Poirot” who takes to heart the relationship problems of the nice women in the novel whom he encounters. Moreover, his past relationships with the Papapolouses and the theatrical agent Joseph Aarons (all of them are Jewish and are not portrayed invidiously) give Poirot a cosmopolitan air. Poirot’s relationship with Georges too is a delight. (Poirot will meet Mr. Goby much later on in the twilight of the series.)

Speaking strictly for myself, I did at all not miss the stolid English presence of Poirot’s faithful, dim, eminently English Watson, Arthur Hastings. How shocked mon ami Hastings would have been by all the low proceedings in wicked France! I have to conclude that The Mystery of the Blue Train is very much an underrated Christie, not only by many crime fiction experts and fans, but by Christie herself. The book almost brought back to me the experience of reading a Christie all anew and that was much appreciated. Yet I had not boarded merely on a nostalgia trip.

The Mystery of the Blue Train is a more sophisticated book than the twelve-year-old me could ever possibly have appreciated. I believe the novel probed too deeply emotionally for Christie herself, who later, after she had found contentment with Max, just wanted to forget those painful years when her first marriage broke apart into a hundred jagged shards (or more) of misery and she notoriously disappeared. Yet anyone taking a ride on Christie’s Blue Train today will in my view be embarking on one of the most intriguing rides in the Crime Queen’s vast corpus of crime fiction.