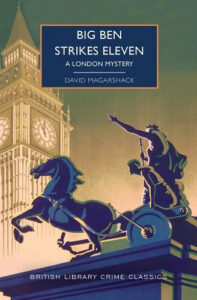

Big Ben Strikes Eleven, originally published in 1934, was the first of three detective novels written by a remarkable man who later earned renown as a translator. David Magarshack boldly gave the sub-title A Murder Story for Grown-Up People to the original printing of this story about the death of the rich and (naturally) unpleasant Sir Robert Boniface, who is found shot in his blue limousine. At first it seems possible that he committed suicide, although so far as the reader is concerned, the sub-title kills off that explanation for his death. We are introduced to a fairly narrow range of suspects, and the detective work is undertaken not by a brilliant amateur but by two Scotland Yard men, Superintendent Mooney and Inspector Beckett.

Dorothy L. Sayers gave the novel a warm reception in a review for the Sunday Times: “a very jolly book, with sound plot, some good characterisation, and everything handsome about it.” She thought his sub-title meant “that the motives and behaviours of his characters are such as the adult mind can reasonably accept” and judged the novel to be the best of the week. The Times was equally enthusiastic: “A first rate detective story…all sound, quick and exciting.”

The Manchester Evening Chronicle was also impressed: “A detective story that will rank amongst the finest of the year. The story is extremely complicated, but so skilfully is the material handled and so cleverly are the main points brought out that one never realises it while reading. Mr. Magarshack makes his characters all real and convincing. His psychology is as good as his deduction.”

No doubt much encouraged, Magarshack quickly followed up his debut with Death Cuts a Caper in 1935. But it is one thing to write a good mystery novel, quite another to produce high-calibre crime fiction time and again. Sayers was less enthusiastic about the second book: “the creaking of the machinery is not sufficiently compensated by the undoubted cleverness of its morbid psychology.” A third mystery, Three Dead, soon appeared in 1937, but then Magarshack abandoned crime writing and concentrated on the work that was to make his name.

In my introductions to British Library Crime Classics, I have often mentioned the help that I receive, sometimes from complete strangers, in working on this series. This novel offers a good illustration of the serendipitous way in which things can develop, often over a period of several years. While researching Peter Shaffer’s The Woman in the Wardrobe, published in the series a few years ago, I had the pleasure of meeting Peter’s brother Brian and sister-in-law Elinor. Elinor Shaffer, an eminent academic, introduced me to Professor Muireann Maguire of Exeter University, a fan of the series who asked if I might consider recommending the detective novels of David Magarshack to the British Library. Muireann in turn introduced me to Dr. Cathy McAteer, the leading expert on Magarshack’s work, which she discusses in depth in Translating Great Russian Literature: The Penguin Russian Classics. I am indebted to Cathy and Muireann for the information and help they have kindly provided to me in order that I could compile a detailed account of Magarshack and his crime fiction. Without their encouragement and enthusiasm, I doubt this rare book would be making a fresh appearance in the twenty-first century.

David Magarshack was a Jewish intellectual, born in 1899 in Riga, now the capital of Latvia but then part of the Russian Empire. After the Russian Revolution, he feared that repressive regulations targeted at Jewish people would make it difficult for him to pursue his educational ambitions, and he moved to England in 1920. His arrival in the UK coincided with the tail-end of the so-called “Russian craze”, that is, the Edwardian readership’s fascination with Russian literature spanning 1885 to 1920.

Interestingly, various biographical details connect Dostoevsky and Magarshack. Both men, for instance, turned to writing as route in part as a response to financial pressures. For Dostoevsky, writing became a means for recovering gambling losses. For Magarshack, writing offered a potential route out of the “tight corner” (as he explained to the editor of the Manchester Guardian) in which he found himself at the end of the 1920s and throughout the 1930s. Financial need not only dictated the fast pace at which Dostoevsky and Magarshack both worked, but also resulted in less-than-standard rates of payment to which they each agreed; Magarshack agreed to a much-reduced rate of royalty for his Penguin translation of Crime and Punishment on the understanding that Penguin would proceed with high-volume print runs. Both men were helped by capable wives; Elsie Magarshack, a Yorkshire-born Cambridge graduate of English corrected and proof-read each of Magarshack’s publications and continued to chase royalties and publicity after Magarshack’s death in 1977. And both writers recognized the benefits of recycling previously successful literary formulae, applying them to their own works.

Magarshack was aware of the parallels. He said in his notes that a “good” translator must possess the ability to “crawl into the mind of his author”, and it seems he made a con- scious attempt to work in the Dostoevskian tradition when writing detective fiction. As Penguin’s first translator of all the key works by Dostoevsky between 1951 and 1958 and Dostoevsky’s first biographer in English, Magarshack owed much of his later literary success and reputation to the great Russian author. His three detective novels failed to provide Magarshack with the literary breakthrough he longed for, but they suggest a literary link with Dostoevsky as a crime writer. In her essay “Crime and Publishing: How Dostoevskii Changed the British Murder”, Muireann Maguire acknowledges a critical reluctance to celebrate Dostoevsky specifically as a crime writer, pointing out that Leonid Grossman’s description of Crime and Punishment as “a philosophical novel with a criminal setting” neatly emphasises the extent to which Dostoevsky’s interest in crime has been perceived as playing second fiddle to his philosophy.

Magarshack’s novels attempt to capture both the philosophical and the crime elements of Dostoevsky’s writing. He recycles key themes such as overdue rent, murder, and close police surveillance; thus, Porfiry Petrovich finds new life in Inspector Beckett and Superintendent Mooney. As Cathy McAteer argues, for Magarshack, these motifs are reworked for a British readership. Magarshack also experiments with Dostoevskian philosophizing, description, and characterization, as in his exploration of genius in this novel. His musings about whether it is a burden or blessing for a person to have genius bestowed upon them and whether genius impacts upon an individual’s actions are reminiscent of the self-obsessed narrative of Dostoevsky’s Underground Man and of Raskolnikov, the protagonist of Crime and Punishment. In this story, Magarshack’s debt to Dostoevsky is evident, in the way he transposes Raskolnikov’s imagined Napoleon to the culturally-modified context of British commerce: “Sir Robert had justly been called a Napoleon of Industry. The question was whether civilisation, which had made such tre- mendous strides since Napoleon on the perilous road of self-realization, could survive another Napoleon?… The time was coming when the civilized world would have seriously to consider the alternative of either putting its Napoleons to death or of perishing by their swords.”

Right from the start of this novel, there are echoes of Dostoevsky. The first sentence evokes, if distantly, the style and mood of the opening lines of Crime and Punishment. Dostoevsky gave distinctive voices to characters play- ing minor roles in his novels, and so did Magarshack. It is impressive that Big Ben Strikes Eleven was published only a decade after Magarshack graduated from University College, London, having arrived in the country with scarcely any English. After his third novel was published, however, he found that translation work was more remunerative. For all its merits, his fiction didn’t yield the financial or reputational rewards he’d hoped for.

Magarshack was one of a large number of people better known for their achievements in other fields, who tried their hand at detective fiction during the “Golden Age of Murder” between the wars. Examples range from A. A. Milne and Billie Houston to Ronald Knox, J. C. Masterman, and C. P. Snow. They were drawn to the genre for a variety of reasons, including its perceived intellectual rigour and, no doubt, the prospect of commercial reward. Sustaining a career as a crime writer, however, presents serious challenges and is hardly a guarantee of easy money. Most of the dabblers fell by the way- side, at least so far as the genre is concerned. But their work is often interesting and enjoyable, and Magarshack’s debut novel certainly deserves this fresh life as a British Library Crime Classic.

***