On March 29th, we lost one of our brightest lights in the crime genre—a man who earned his way into the pantheon through crafting the darkest crime fiction. Ken Bruen passed away in his native Galway, Ireland, a city he often wrote about, especially in his Jack Taylor series. To read him was an experience like no other. To know him, even more.

When his work hit the U.S. crime fiction community, it was like rock fans and musicians discovering Hendrix. Young (and a few older) writers wanted to emulate him, but you couldn’t. You could learn, but not imitate. Only Ken could pull off what he did. He utilized his background as a poet for his tight yet meandering tales. His sharp elliptical style and punk rock attitude sharply dissected the rotten heart of society.

He loved language and played with it. Many of his books had a word in the title with several meanings and one of the themes was examining those meanings. Unlike many who moved from general fiction to the genre, he didn’t feel the need to apply a “literary” style to it. He respected the literary elements already present in noir, and mining the classics of the genre for inspiration while creating a style all his own.

Before becoming a published poet and novelist, he spent decades traveling the world. After earning a PhD in Metaphysics, he taught English in Japan, Africa, Southeast Asia, and South America, even spending four harrowing months in a Brazilian prison. Ironically, he mainly turned to his home country when it came to his writing.

After a tentative start with a handful of general fiction, in 1996 he arrived in genre with the bold, brutal, and poetic Rilke In Black. The story of an ex-bouncer drawn into a kidnapping scheme by his drug addict girlfriend used a Jim Thompson template to launch his unique characters and style. His losers on the edge peppered their language with both pop and high culture. Full of dark humor and intense moments, often at the same time, the book established what Ken would be to crime writing. He excelled even more with his follow up, The Hackman Blues. He gets into the head and voice of Tony Brady, a gay, manic-depressivebody builder who moonlights as hired muscle . When he gets recruited by a bigoted businessman to get his daughter away from a Black club owner with questionable connections, things soon get out of hand as Tony and his former prison mate, Elias Rasheed Muhammed, decide to play both parties against each other and Tony goes off his lithium. Ken’s style captures Tony’s emotional and mental swings and the instability of the world at large.

Ken’s first first series followed the happenings of a Southeast London police station. Picture a British version of Ed McBain’s 52nd Precinct novels, a series to which it pays direct homage,, but with more infighting and dysfunction. . The central character is Detective Sergeant Brandt, an Irishman with a chip on each shoulder, who often dispenses justice with a Hurley stick. He describes the sport as “one-part field hockey, one-part murder”. In the series Bruen weaves a tight tapestry of compromised coppers and their oft-psychotic quarry.

The author found his true vessel in a singular character: the misanthropic, drug-and-alcohol-addicted ex-Guardia Jack Taylor. In The Guards, his first appearance, Jack has just lost his law enforcement job when he punched out a magistrate and now works as an investigator, although he has trouble leaving the pub stool to actually pursue his cases. Many in crime fiction consider the series to be the epitome of noir, as the cases take Jack into lower and lower depths, damaging his soul and psyche with each book.

The series also worked as a social profile of Galway and Ireland through the new century’s sudden prosperityand equally rapid economic decline. As the series progressed, he placed current events into each novel, interpreted through Jack’s increasingly cynical eyes. I asked Bruen in our last interview if the books reflected Taylor’s view of Ireland or Ireland’s view of itself.

“The country I write about is so much darker than in reality, but every day, we seem to be getting closer to the noir I envisage.”

Ken is also memorable as one of the rare authors who could collaborate with others. With Jason Starr, he wrote a series of increasingly meta stories, full of humor, that reflected crime’s relationship with different media. On a more somber tone, he worked with Reed Farrel Coleman on Tower, a brutal, beautiful tale of two friends dealing with crime, betrayal, and powers larger than themselves. Each took the point of view of one of the friends, and as a team, these two poets and rime writers produced a poignant heart breaker.

He probably collaborated so well because he loved his fellow writers. The Jack Taylor novels are famous for mentioning other books and authors. In interviews he often mentioned others in the field, particularly ones just starting out and in need of a boost. Even when I first met him, my first year at L.A.’s Mystery Bookstore, he treated me like a colleague and was supportive of my writing and my work as a crime fiction critic.

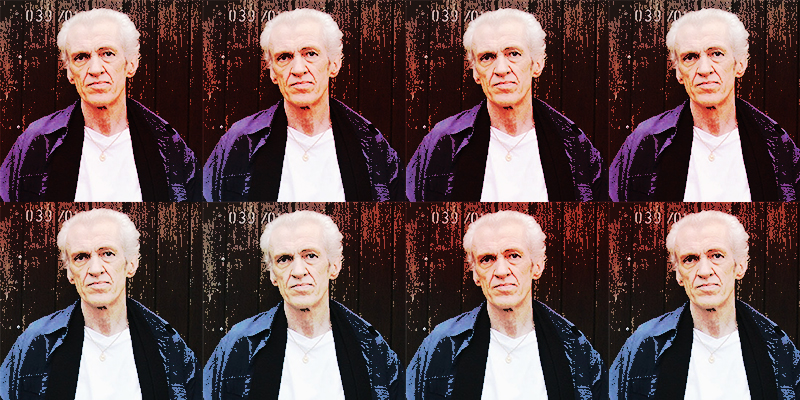

However, you didn’t want to be an author who got on the wrong side of him. When he signed at The Mystery Bookstore, a lady came up with his British copies. He help up one and said that the cover with an unflattering blurred close up of a woman had a story. He proceeded to tell how after Rilke On Black and The Hackman Blues came out, a popular British mystery author condemned his books because they lacked moral fiber. His answer was yes, they’re noir. The offended author approached a critic who felt the same way and wanted to see what they could do to stop these “low Irish” who were invading the British literary scene. This was a joy for Ken to hear. “I was going to be a banned Irish author. I would be up there with Joyce.”

When the two learned they were playing into his hands, they backed off. Still, as Ken said, “I wanted to put the knife in.”

So he when his the second novel with Brandt, Taming The Alien, came out, he had a distorted photo of the author put on the cover. “I sent her a free copy, never got a thank you note. Some people have no class.”

When I was catching up on The Jack Taylor books, I noticed the antagonist, a professor of literature, strongly resembled an oft-criticized writer of both literary and genre fiction. I asked Ken in our long-running email correspondance if he based that villain on who I thought. In less than five minutes I got an email response—

Spot on Mr. Montgomery. I love those literary types who think they’re slumming with us crime folks.

That professor character received one of the worst deaths I ever read.

Those emails also demonstrated his talents. Full of wit, warmth, and precise word choice they captured the essence of the chat one has with a friend. What makes it even more amazing is that I only hung out with him in person that one time at the store. Still, he made me feel like we’d sipped Guinness and Shiners together for years. If you read anything of Ken’s, it left an imprint.