One night in 1970, Rena Pederson, a young wire-service reporter organizing news bulletins printed by the Dallas office’s teletype machines, came across a dispatch about an audacious crime. The so-called King of Diamonds was at it again, absconding from a local mansion with jewels worth an estimated $60,000. “That,” Pederson recalls, “was ten times what I made a year at UPI.”

The clever crook, it seemed, had been active for years, stealing from dozens of homes owned by Texas tycoons whose new money came from oil wells and retail empires. Pederson would spend the next several decades amassing an impressive journalistic resume, but even as she climbed The Dallas Morning News’ masthead and published several books, she didn’t forget the never-caught thief.

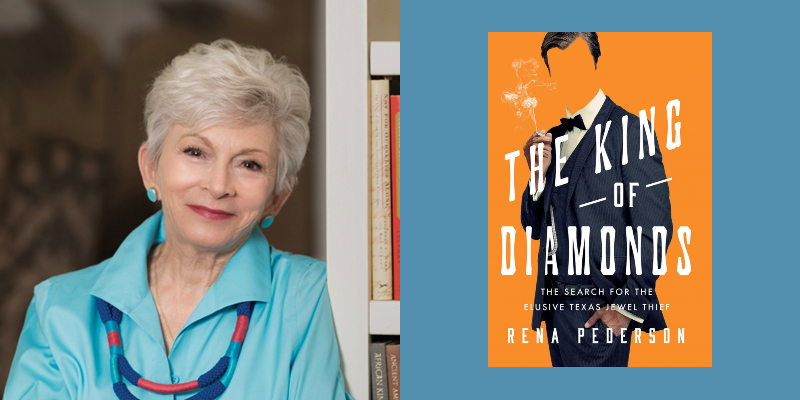

In the mid-2010s, Pederson realized she finally had time to write about the “king,” as the press dubbed him six decades ago. The product of interviews with more than 200 people and countless hours spent digging through newspaper archives, her new book—The King of Diamonds: The Search for the Elusive Texas Jewel Thief—is informative and entertaining, a game effort to solve a batch of sensational crimes that coincided with Dallas’ midcentury economic boom and the assassination of President John F. Kennedy.

Speaking from her home in Austin, Pederson discussed the thief’s intriguing crime spree, which, she calculates, netted jewels that would be worth $6 million today.

By 1970, how long had the thief been active?

I would say that the thefts were going on for at least a decade by then. Once I checked the records, I realized that they probably started in the mid-50s.

Who was the thief stealing from?

It was a very special time in Dallas, I guess you would say. Oil money brought incredible riches pouring into what was basically a very rural, poor state. Dallas was full of Gatsbys, because that’s where the bankers were, and they would take a risk on a well for a share of the profit. Dallas was essentially a small city, with rich people who were like sparklers on the cake.

That aspect of the book makes it a portrait of Dallas becoming the place we know today. Did you realize from the start that you writing a sort of history of the city in the 20th century?

At first, I didn’t. I thought, well, this guy was so good, he had to be a pro, and he probably ended up in some other jurisdiction. But the more I got into it—and the more the police got into it—I realized it was someone living in Dallas, because it went on for so long in a very contained space. It had to have been somebody who knew these rich people, because the thief was so intimately familiar with their houses. You had to look at the culture, because the culture created this moment, this perfect storm of money and glamour.

The people whose homes were robbed belonged to swanky golf clubs and night spots. And you think that more than 20 had some sort of link to the Dallas Opera?

When you have people who are newly rich, they want respectability, they want a place in society. So what they did was join the opera. They dressed up to go to the opera because that’s what rich people in New York and Boston did.

How exactly did the thief work?

Usually, a burglar will come when people are out of town and there are no lights on, and papers are piled up in the yard. That’s the thing that was confounding to the police—he would come into people’s homes while they were in their beds, walk by their beds, sometimes hide in their closets.

That was my favorite detail from the book, that he seems to have wanted people to be at home, because if they were, their jewels would be there too.

Correct, and the burglaries were happening in a finite area, two-and-a-quarter square miles. When the police made a spreadsheet, they realized that most of the crimes occurred between October and March. Well, that happens to be social season in Dallas, when people have their jewels at home—you don’t want to be running back and forth to the safe at the bank.

If the jewelry-owners wanted to be seen looking fancy at the opera, the thief also seems to have had something to prove.

He only went after the best jewelry. He only took women’s jewelry. He would leave thousands of thousands of dollars in jewels if they weren’t the best. Some men, just to prove how much money they had, wore these big gold Rolex watches with diamonds. He wasn’t interested in those.

And none of these items ever turned up for sale anywhere?

No, and that added another layer to the investigation. The only people who might be able to get the jewels out of town, to Europe or wherever, would be organized crime.

You think you might’ve figured out the identity of the thief. I won’t spoil the ending here, but I was wondering if you can talk about narrowing down your suspects.

I found that as it went on, and as their neighbors were being hit, people suspected their neighbors, they suspected someone dancing next to them who looked like they were wearing expensive jewels that they couldn’t afford. Everybody’s suspected everyone else, so that gave me more suspects. I had to pare it down, and what I did is, if somebody’s name came up at least 10 times, then I would look more intensely and in more detail at them.

I ended up with about five lead suspects, and I could have made a good case for any one of them. And that’s one reason it took longer than expected to finish the book, because I wasn’t investigating just one burglary—there were over 60 that I could document, and I suspect there were at least 100. Some people didn’t report them, because they didn’t want their neighbors to know that they had been burgled or how much jewelry they had.

Though the crimes happened decades ago, you were able to interview a lot of people who lived through this, including cops and reporters.

I’m so glad I started when I did. I would say at least a third of the people I interviewed have died since then. I feel so fortunate that I got to them in time to get their oral histories. Some people were eager to talk about it because it felt like it had just happened yesterday. It was still very real to them.

As you say in the book, you can’t talk about Dallas in the 1960s without discussing JFK. How did that affect the pace of the crimes and the investigation into them?

Dallas police were pulled away from the case, of course, to deal with the catastrophe that the Kennedy assassination was. They pulled one officer to reinvestigate what had gone wrong in the protection of Lee Harvey Oswald, and how Jack Ruby (who shot Oswald on live TV) got into the police station.

But two weeks after the assassination, jewels were taken from an architect’s home that was only a couple blocks from the police station. So the King of Diamonds wasn’t in shock. He wasn’t mourning. He was doing what he did—he wanted things, so he took them.