“I have wrought my simple plan,

If I give an hour of joy

To the boy who’s half a man,

Or the man who’s half a boy.’

‘That’s my foreword,’ declared Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, the creator of Sherlock Holmes, as he neared completion of his famous novel The Lost World in November 1911: ‘It will be more a boys book than any I have done.’

But it would be much more than that, becoming a favorite of many a man long after first discovering it as a book. Though universally known for Sherlock Holmes, Conan Doyle wrote much else in his lifetime. By 1911 he was known also for historical novels like The White Company and Sir Nigel, about England’s Middle Ages; for Brigadier Gerard, a picaresque series about the comical misadventures of one of Napoleon’s officers; for stories based upon his own years of medical education and practice; and more. Now he was at work on something new for him that harked back to his boyhood, when at age fourteen he’d told his mother: “I am trying to improve in my French and I have read a great many books in that language lately. I will tell you a few of them to see if you have ever seen them. Vingt milles lieues sous les mers by Jules Verne—Cinq semaines en ballon by Jules Verne.”

Verne’s visionary work took root in Conan Doyle’s mind, and at twenty-six, in 1885, so did H. Rider Haggard’s bestseller King Solomon’s Mines, a tale of adventure in a lost world of its own. By 1889, with three novels behind him now, including the first Sherlock Holmes tale A Study in Scarlet and a well-received historical novel called Micah Clarke, Conan Doyle felt an urge to write an outright adventure:

“I am thinking of trying a Rider Haggardy kind of book called “the Inca’s Eye” dedicated to all the naughty boys of the Empire, by one who sympathizes with them. I think I could write a book of that sort con amore. It would come as a change after Micah. The notable experiences of John H Calder, Ivan Boscovitch, Jim Horscroft, and Major General Pengelley Jones in their search after the Inca’s Eye. How’s that for an appetite whetter.”

In the end, Conan Doyle went in another direction, but did not lose his desire to write a “Rider Haggardy” novel. While he admired authors like George Meredith and Charles Reade and his own contemporary, Thomas Hardy, he preferred to write Romances and Adventures. Even being a doctor was a Romance to him, embraced in his “The Romance of Medicine” talk in 1910 at St. Mary’s Hospital, London, where his son Kingsley was a medical student. And the scientific consulting detective Sherlock Holmes’s investigations were Adventures as far as Conan Doyle was concerned, rather than Cases, or Mysteries.

By 1911, these tendencies collided with a regret over diminishing “blank spaces” on the world’s map. When a Lost World character remarks that “The big blank spaces in the map are all being filled up, and there’s no room for romance anywhere,” Conan Doyle was quoting himself anonymously, from a talk he’d given the year before at a luncheon honoring the Arctic explorer Robert Peary.

While [Conan Doyle] admired authors like…Thomas Hardy, he preferred to write Romances and Adventures. Even being a doctor was a Romance to him…And the scientific consulting detective Sherlock Holmes’s investigations were Adventures.These factors combined also with a renewed interest in the doctrine of evolution. It had been the foremost scientific controversy of his youth in the 1860s and his medical-student days in the ’70s. In his autobiography Memories and Adventures, Conan Doyle looked back fondly at those years, “when Huxley, Tyndall, Darwin, Herbert Spencer and John Stuart Mill were our chief philosophers, and even the man in the street felt the strong sweeping current of their thought, while to the young student, eager and impressionable, it was overwhelming.”

In the 1880s, an article in a monthly periodical which Conan Doyle read avidly, Nineteenth Century, may have struck a chord. By 1907, as he continued to turn out Sherlock Holmes, commentaries like Julian Hawthorne’s notes for the Library of the World’s Best Mystery and Detective Stories were noting similarities between Holmes’s deductive reasoning and Voltaire’s Zadig. Eye-catching for Conan Doyle, then, may have been “On the Method of Zadig” in the June 1880 number of Nineteenth Century by the great scientist T. H. Huxley, known as “Darwin’s Bulldog” for his advocacy of Darwin’s theory of evolution. In Memories and Adventures Conan Doyle would call Huxley one of the “pilots” of his early years.

Huxley had described how Voltaire’s Babylonian philosophe used uncommon powers of observation and deduction to astound those around him, in order to show how this reasoning process should be employed in scientific investigation. “From freshly broken twigs, crushed leaves, disturbed pebbles, and imprints hardly discernible by the untrained eye,” Huxley wrote, in tones Sherlock Holmes himself might have used,

“such graduates in the University of Nature will divine, not only the fact that a party has passed that way, but its strength, its composition, the course it took, and the number of hours or days which have elapsed since it passed. But they are able to do this because, like Zadig, they perceive endless minute differences where untrained eyes discern nothing; and because the unconscious logic of common sense compels them to account for these effects by the causes they know to be competent to produce them.”

Moreover, one such University of Nature graduate discussed by Huxley was the French scientist Georges Cuvier, praised similarly by Sherlock Holmes in the story “The Five Orange Pips.” As the “founding father of paleontology,” Cuvier had laid the foundations of what Challenger’s party discovers in The Lost World’s “Maple White Land”—living dinosaurs, and “Missing Link” ape-men. It was an allied science about which Conan Doyle also consulted a naturalist, the zoologist Edwin Roy Lankester, author in 1906 of Extinct Animals.

“Romance writers are a class of people who very much dislike being hampered by facts,” Conan Doyle had said at the 1910 luncheon for Robert Peary, but in practice he strove to make The Lost World’s settings and evolutionary science as factual as expert knowledge would permit within his adventurous and romantic plot.

The Lost World’s main characters reflect this, along with an important undertaking of the author’s own. Professor George Edward Challenger is a scientist of unorthodox nature, in appearance and personality also: “a Columbus of science,” enormous in stature, bearded like an Assyrian bull, with masterful eyes and “a bellowing, roaring, rumbling voice,” and a violent temper when challenged. Yet a tender streak too, especially for his wife—making him, as Conan Doyle’s daughter Dame Jean observed, a “strangely endearing” character. The original Challenger was in fact a notable physiology professor whom Conan Doyle had had in medical school, William Rutherford—saying in Memories and Adventures that “He fascinated and awed us.” Challenger was “a character who has always amused me more than any other which I have invented.”

Opposite Challenger is a professional skeptic, Professor Summerlee, “a thin, tall, bitter man with the withered aspect of a theologian.” Conan Doyle may not have had a specific model for Summerlee in mind from his Edinburgh University days, but he had witnessed rivalries between professors, not only over Darwin’s doctrine of evolution, but also the on-going conflict in medical circles over germ theory and antisepsis. He had visited such scientific antipathies before, in “His First Operation” from Round the Red Lamp: Facts and Fancies of Medical Life (1894), as two students watch a surgical demonstration: “Who are the two men at the table?” — “One has charge of the instruments and the other of the puffing Billy. It’s Lister’s antiseptic spray, you know, and Archer’s one of the carbolic-acid men. Hayes is the leader of the cleanliness-and-cold-water school, and they all hate each other like poison.” And so in The Lost World, there occurs “a hush over the hall, the students rigid with delight at seeing the high Gods on Olympus quarreling among themselves.”

Trying to make the best of Challenger’s and Summerlee’s feuding are the novel’s other two principal characters, Lord John Roxton and Ned Malone. Roxton, a soldier of fortune, appears based upon two men whom Conan Doyle knew. Roger Casement was an Anglo-Irish diplomat in Her Majesty’s Government who had collaborated with him and others against Belgian atrocities in the Congo—a human-rights campaign Conan Doyle chronicled in his 1906 nonfiction book The Crime of the Congo. Like Casement, Roxton is a champion of justice when it comes to abused natives encountered in his explorations, with the sense of fair play Conan Doyle himself had learned as a sportsman. The second model was Percy Fawcett, a British Army officer and intrepid explorer of South America whom Conan Doyle consulted regarding Lost World settings in that still not fully explored continent.

And it is Ned Malone, a young London newspaper reporter recalling the sketch artists of that day, who narrates the novel. Modest and diffident, Irish like Conan Doyle himself (who though born and raised in Scotland was Irish on both sides), he sets off on this adventure thanks to his “Irish imagination” without realizing what he is getting himself into. Just as Conan Doyle had when, aged twenty, he left medical school for six months aboard an Arctic whaler as its not altogether qualified surgeon—neither he nor Malone regretting the impulse after they got home safely.

Conan Doyle became so enamored of Professor Challenger in the process of creation, that when it was done he continued to give close attention not only to the illustrations for it, but also prepared, with his artist brother-in-law Patrick Lewis Forbes and professional photographer William Ransford, a set of photographs of themselves as the novel’s main characters—Conan Doyle himself disguised as Professor Challenger. “In an impish mood,” he confessed, “I and two friends made ourselves up to resemble members of the mythical exploring party, and were photographed at a table spread with globes and instruments. . . . I had an amusing morning touring London in a cab and calling upon one or two friends in the character of their lost uncle from Borneo.”

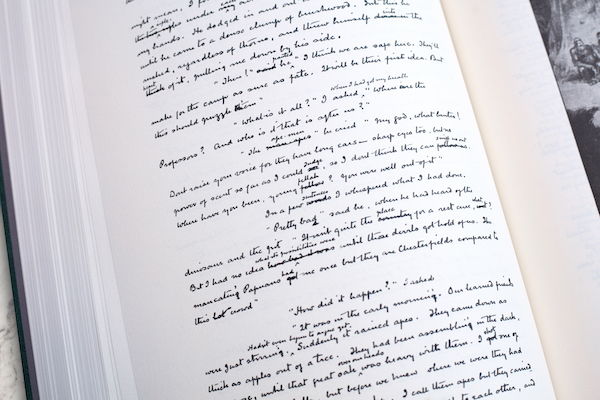

The Lost World was written in the autumn of 1911, and completed by December 3rd. Like most of Conan Doyle’s manuscripts, this one has occasional interlinear additions but not very many deletions. At one point a large paragraph about interpreting Time’s changes through fossils is crossed out, but more about it is included later on. It is risky to conclude too much from a manuscript, but as one observes Conan Doyle’s handwriting becoming ‘busier’ in the course of composition, then grow more leisurely and once again busier, covering both sides of the paper, it is impossible not to feel the author’s excitement and impatience to reach the climax, until finally the edits grow very few in the concluding chapter.

“It promises to be a great success,” he felt: “I should not be surprised if it is not the best seller of any book I have ever done.” Serialized in the Strand Magazine starting in April 1912, his longtime editor there, H. Greenhough Smith, called it “the very best serial (bar special S. Holmes values) that I have ever done, especially when it has the trimmings of faked photos, maps and plans.” It was a tremendous success with the public, then and when brought out between hardcovers that October by the firm of Hodder & Stoughton.

By that time, Conan Doyle was far into a sequel, The Poison Belt: more pioneering science-fiction, with Conan Doyle harkening this time not only to Jules Verne, but also to his fellow writer and friend H. G. Wells, while drawing again upon the scientific education he had received at Edinburgh. The Poison Belt was followed in 1926 by another sequel, The Land of Mist, and pastiches of Professor Challenger by other writers had appeared as early as 1919. Conan Doyle returned to Challenger twice more in his final years, more science-fictionally than ever in the short stories “When the World Screamed” in 1928 and “The Disintegration Machine” in 1929. (The influence of Jules Verne’s Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea which he had read as a boy was evident in another science-fiction novel in 1929, The Maracot Deep, in which undersea explorers travel to a kingdom on the ocean floor.)

In 1925 the first of many Lost World movies and radio/tv programs had come out, starring Wallace Beery as Challenger. Its pioneering stop-motion animation, depicting dinosaurs cavorting alarmingly, was previewed by a mischievous Conan Doyle himself at an excited Society of American Magicians dinner in New York in June 1922; and in April 1925, it became the world’s first in-flight movie entertainment on an Imperial Airways flight from London to Paris.

Now, nearly a century later, it is not a question of if another dramatization of The Lost World will appear, but when. And this manuscript was the start of it all.

***