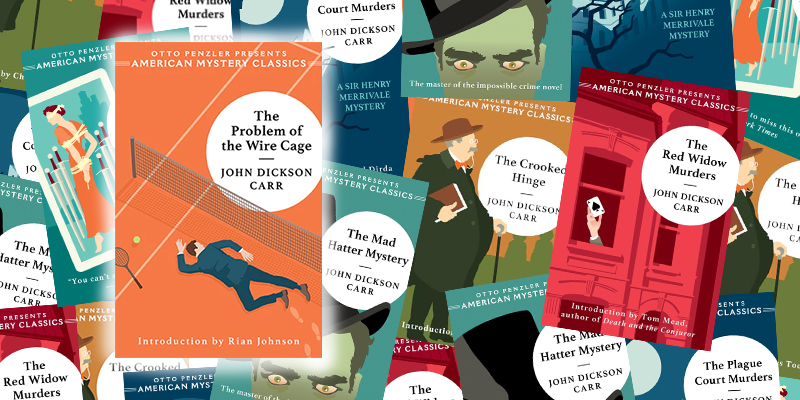

You hold in your hands one of Otto Penzler’s American Mystery Classics, a series that resurrects out-of-print gems in handsomely designed new editions. I owe this series a great debt because it introduced me to the work of one of my favorite mystery authors, John Dickson Carr.

Carr was an American but lived and worked in England during the 1930s. Outlandishly prolific, he quickly built a body of work that placed him in the pantheon of what is now known as the “golden age of detective fiction.” This isn’t the brute poetry of Hammett or the seedy sexual decay of Cain, no Spades or Marlowes or gumshoes packing gats. This is murder as a gentleman’s game, the fair play of master puzzle-smiths, or to quote Anthony Shaffer quoting Philip Guedalla, “the normal recreation of noble minds.” This is Agatha Christie, Dorothy L. Sayers, Ellery Queen, G.K. Chesterton. Carr is less well known today than those contemporaries, and that deserves to change, because he is one of the very best.

The first quality that blows your hair back in any of Carr’s novels is so fundamental that it’s easy to take it for granted: beyond the plotting or the puzzling, beyond the mystery itself, first and foremost the man is just one hell of a writer. Like walking into a well-put-together room, when you’re in the hands of a good writer you can just feel it. His prose is genteel without being fussy, brisk but rich, funny while keeping your feet in the dirt, and all of it woven with that effortless breeze of step that we as readers recognize and happily fall in behind. To quote Sayers, no slouch herself:

“Mr. Carr can lead us away from the small, artificial, brightly-lit stage of the ordinary detective plot into the menace of outer darkness. He can create atmosphere with an adjective, alarm with an allusion, or delight with a rollicking absurdity. In short, he can write.”

That menace she mentions is palpable in Carr’s work. Tonally his books lilt towards the gothic horror of Poe, often turning from cozy warmth to chilling terror on a dime. Yes, you’ll get the comforting burnished warmth of libraries and club chairs, but it’s when the story blows the windows open and the candles out that Carr really shines. Hag’s Nook, another of my favorites, centers on the events of a dark stormy night in a crumbling ancient prison. What could have been a hoary trope of a setting is in Carr’s hands a sensual feast of rotting, rat-infested terror, so effective that, though we know the essential cozy moral compass of the genre will not be betrayed, at moments our sense of security slips away, leaving the thrill of “oh god what if this gets truly nasty?”

The Problem of the Wire Cage has a relatively genteel setting, an English estate with an adjoining tennis court. The clean lines and manicured safety of a gentleman’s game. But it has images of unsettling power that have stuck in my mind as much as any gothic dungeon. Carr begins it with a storm. Violent disruption. The electric smell of lightning in the air and loamy wild petrichor. With a few brush, strokes the blackened clouds frame pastoral green, the driving brutality of the rain and wind cuts the structured idyll, and we feel the invasion of something dangerous and primal, all the more effective for its contrast with the comforting.

In that way, Carr’s similarity to Poe goes beyond style. Although the resolution will always solve the crime, turn on the lights and restore order, it’s obvious that that is not where Carr’s heart lies. In fact, to risk sacrilege here, though Carr is one of the premiere puzzle constructors of his age and his denouements are always surprising and satisfying, those final chapters are consistently my least favorite part of his books. The beating heart of any John Dickson Carr tale is the delicious terror of the unsolvable, the tactile details of the unexplainable and horrific, and the implication that the monster is just outside your window. All your careful structure and cozy comforts will not protect you from the darkness.

But let’s talk about puzzles.

Carr is known as a master of a very particular subset of detective fiction, the “locked room mystery.” In the most literal sense this is exactly what it sounds like: a corpse is found alone in a locked room, knife in his back, but he is alone and there are no ways in our out, bah dah dum. With such a constrained premise there are only a few real options to work with, usually some combination of ingenious contraption and manipulated timeline. It’s the mystery version of a chess puzzle, with just enough pieces on the board and no more, a few predetermined moves at your disposal. If you can stand another metaphor, it’s also the mystery equivalent of a margarita pizza—possibly the purest test of a pizza artisan’s skill in that its simplicity leaves nothing to hide behind. The most famous of Carr’s locked room mysteries is his masterpiece The Hollow Man, titled The Three Coffins in the United States, which features a little meta mini-lecture from the detective on the solving of locked room crimes. It’s creepy and ingenious and delightful and, if you’re new to Carr and enjoy what you read here, it should probably be your next book.

But even an author as ingenious as Carr could not work in rooms his whole life and most of his books open up the locked room concept to its (in my opinion) much more fun cousin, the “impossible crime.” This brings us back to our present volume, The Problem of the Wire Cage. A man is dead, strangled in the center of a sandy tennis court after a rain, with just his own footprints leading to his final resting spot.

It’s as clean and beautiful a set-up as you could ask for. Graphic and perfectly clear, it presents the impossible challenge to the reader in one single striking image. This might be why Anthony Shaffer begins his film adaptation of Sleuth with fictional mystery writer Andrew Wyke (modeled to some degree on Carr) narrating the denouement of his latest novel with this exact same premise. The film opens with Wyke (played by Laurence Olivier) standing in a hedge maze, listening to his dictation recording of this passage:

“But since you appear to know so much, sir,” continued the inspector humbly, “I wonder if you would explain how the murderer managed to leave the body of his victim in the middle of the tennis court and effect his escape without leaving any tracks behind him in the red dust. Frankly, sir, we in the Police Force are just plain baffled.”

Sleuth is one of my favorite films. I can recite the rest of this scene verbatim and I put a reference to a case involving a tennis champ into my own film Knives Out as a tribute, so I was greatly relieved that Shaffer did not spoil the actual solution to Wire Cage. He does, however, take great pleasure in spoiling the idea that cozy detective fiction is the “normal recreation of noble minds.”

The locked-room or impossible-crime mystery has its detractors. Some find the solutions by their very nature to be overly theatrical, fussy, and belabored. Very often the crime is impossible in a way that implies some supernatural element must have been involved and, for children of the 1970s, this can have the unfortunate effect of evoking two words every mystery writer dreads… “Scooby Doo.”

I wouldn’t go that far. But look. I do get it. I can appreciate the fun of an ingenious puzzle, especially when an artist of Carr’s caliber is crafting it. But these types of set-ups have much in common with magic tricks and there will inevitably be something slightly anticlimactic and tawdry when the mechanism behind even (or especially) the best trick is revealed.

So why is Carr, the foremost practitioner of this method of mystery, one of my favorite authors? To put it simply: his best work never mistakes puzzles for story[/oullquote]

So why is Carr, the foremost practitioner of this method of mystery, one of my favorite authors? To put it simply: his best work never mistakes puzzles for story. And he’s a damn good storyteller. His books may be known for their puzzles, but they’re powered by the narrative engine and driving pace of a Hitchcock thriller.

The Problem of the Wire Cage is a fantastic example of this. I’ll tread lightly here so as not to spoil any of the book’s delights, but in the very first pages Carr yanks you right in with a love triangle, complimenting the rising rainstorm with jealous violence. Then, even more crucially, when the mystery of the body in the middle of the tennis court is revealed, Carr does not rely on the detective’s investigation to hold the reader’s attention. Instead, he takes the two characters we care about the most and snares them into a web of guilt and culpability. Suddenly we are not thinking out a puzzle but flipping pages on the edge of our seats to see how these two could possibly get out of it.

I sincerely hope by this point you’ve skipped ahead and just started reading the damned book but, for the patient ones still with me, I’d like to end with an appreciation of Dr. Gideon Fell. Carr created several detectives over his vast oeuvre, but the most famous are Sir Henry Merrivale and Dr. Gideon Fell. Fell features in this book, and he deserves to be ranked with Poirot and Holmes, Marple and Wolfe and Wimsey and whoever else you’d put in the pantheon.

A wheezingly massive man who walks with two canes, with an appetite for beer, cigars, and eccentric knowledge, by turns blustery and sly, blunt and humane, he can be a bull in a china shop one moment, then vanish into the shadows the next. Like all great golden age sleuths, you underestimate him at your peril. Carr modeled him on one of his own heroes, G.K. Chesterton, who authored (among many other things) the Father Brown mysteries. Besides the physical resemblance, Fell reflects Chesterton’s earthy morality. Father Brown’s skill as an amateur detective lies in a loving intimacy, not with the perfectly divine, but the painfully flawed and human. We read the same knowing compassion into Gideon Fell though, if I had to choose one of the two to go out for beers with, Fell would be much more fun.

Enjoy the book! If you’re familiar with Carr’s work, you’re in for some fresh delights. If this is your introduction to the man, I hope it’s the first of many, and that you spread the gospel far and wide. Thanks are owed to Otto Penzler for the opportunity to write this introduction, and for publishing the wonderful American Mystery Classics series. I’d highly recommend the previous Carr volumes, in which you will find illuminating introductions from authors and luminaries such as Charles Todd, Michael Dirda, Tom Mead, and Otto himself.

Rian Johnson

Paris

May 2023

__________________________________

John Dickson Carr, The Problem of the Wire Cage

(American Mystery Classics)