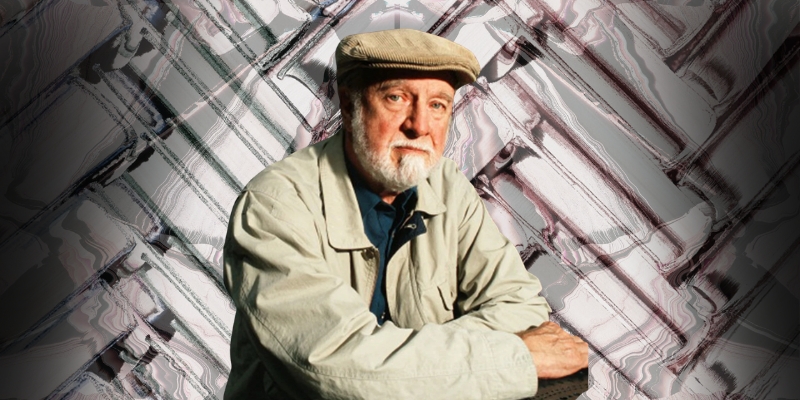

Richard Matheson was one of the fiction writers who spanned generations and genres and whose career is hard to sum up. How do you do justice to an author whose work included the influential novel I Am Legend, numerous Twilight Zone episodes, Roger Corman Poe movies in the 1960s and Duel, the killer truck TV movie that made the career of Steven Spielberg?

Matheson was the Stephen King of his time—and, with all due respect to the King himself—Matheson was the Stephen King of Stephen King’s time as well.

When Matheson died, at age eighty-seven, in 2013, King posted a tribute on his site. “We’ve lost one of the giants of the fantasy and horror genres….Matheson fired the imaginations of three generations of writers. He fired my imagination by placing his horrors not in European castles and Lovecraftian universes, but in American scenes I knew and could relate to. ‘I want to do that,’ I thought. ‘I must do that.’ Matheson showed the way.”

King has been quoted as saying that Matheson influenced him the most of all writers.

How do wrap our brains around the full scope of the work of Richard Matheson, even more than a decade after he died? We can only try.

*

I won’t try to recap Matheson’s life and writing career, histories already well-known to many readers. Instead, I’ll dip in and out of his working life.

When I posted on social media a photo of the copy of The Best of Richard Matheson collection I was reading to prep for this article, a friend commented, “There is no worst of Richard Matheson” and that’s certainly true. Some of his short stories might be better-known than others, but every one of his dozens and dozens of pieces of short fiction has something to recommend it. It’s staggering how, just counting the thirty-plus stories in that 2017 collection, Matheson’s work was represented in so many genres of magazines and anthologies.

There’s “Born of Man and Woman,” of course, in some ways his best-known short fiction. It’s a heartfelt but tough-minded and even shocking tale, first published in the Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction in July 1950. Its story of a pathetic and ultimately vengeful offspring hidden away by its family undoubtedly served as inspiration for many stories, movies and TV episodes in the decades that followed.

(The origins of the infamous “Home” episode of The X-Files, originally airing in 1996, have been oft-told and don’t cite Matheson. But it’s hard to imagine that the story of Scully and Mulder investigating a murderous, mutated family in a remote farmhouse didn’t take some inspiration from Matheson. I’ll note that “Born of Man and Woman” established Matheson’s ingenious tactic of staging stories of the macabre outside gothic settings.)

And yes, there are some very familiar stories in the collection, including ones filmed, like “Duel” and “Nightmare at 20,000 Feet.” But a good number of Matheson’s less fantasy-oriented stories were published by crime and mystery magazines and any of them, for having been published in the 1950s and 1960s, hold up and would be appreciated by readers if they were published for the first time today.

There’s “A Visit to Santa Claus,” published in 1957 in Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine. A man who wants to be rid of his wife and join his mistress in paradise enlists a killer—and makes a downpayment of $100!—to kill his spouse. Meanwhile, he takes their child to see a department store Santa. It’s a tense story with the queasiest main character you’ll meet.

“Big Surprise” is more than a little horrific and was published in Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine in 1959 and later adapted as a Twilight Zone episode (more about the original series in a bit). If you’re looking for horror-tinged crime stories, Matheson was the man.

Of course, Matheson was known for horror and suspense, often in film and movies.

*

Matheson established himself as a leading light of horror and suspense fiction beginning in the 1950s, and his 1954 first novel I Am Legend might be the most famous of his string of tales with great mass-media impacts.

The novel, set in California in the 1970s after a pandemic, is the story of Robert Neville, a survivor of not only the end of the world but of post-end-of-the-world existence. Neville must not only find the supplies to sustain his life but avoid the nighttime predations of his fellow citizens who are still around—but who are now vampires.

If the story sounds familiar, it’s of course because I Am Legend was filmed in 1964 as The Last Man on Earth, starring Vincent Price; The Omega Man, released in 1971 and starring Charlton Heston; and I Am Legend, released in 2007 and starring Will Smith. None of the movies is entirely faithful to the novel.

Matheson was no stranger to big-screen adaptations of his work. His story “The Shrinking Man” was adapted as The Incredible Shrinking Man in 1957 and remains one of the most matter-of-fact sci-fi films. From the worrisome mundanity of altering suddenly ill-fitting clothes to the effect of shrinking away in a marriage to deadly battles with a housecat and a spider, the film is a classic. Matheson is credited on the screenplay.

For much of the decade to follow, the incredibly prolific author moved between short fiction and novels and screenplays. Among the best-loved of his work for film were the Roger Corman movies “based” on Edgar Allan Poe stories, from “The House of Usher” in 1960 to “The Comedy of Terrors” in 1963. The films were Corman’s answer to the full-color horrors from Britain’s Hammer film studio and entertained millions—and still do—with stars like Price, Boris Karloff, Basil Rathbone and Peter Lorre.

For those who paid attention to “written by” credits, Matheson became a creator to eagerly anticipate with sixteen episodes of Rod Serling’s “The Twilight Zone” from 1959 to 1964. Along with Serling, the great Charles Beaumont and a few other talented writers, Matheson made the series the household name it was.

“Little Girl Lost” was a creepy tale of a missing child that no doubt influenced Poltergeist, “The Invaders” featured Agnes Moorehead as a woman in a remote cabin repelling what’s ostensibly an alien invasion, and the classic “Nightmare at 20,000 Feet” starred William Shatner as a nervous airline passenger who spots a gremlin on the wing of the plane. It’s a classic for a reason.

Matheson was a working writer, luckily for all of us, for life, and in the 1970s and 1980s, his screenplays contributed to our nighttime feelings of dread and terror.

*

Matheson’s 1971 short story “Duel” begins innocuously enough: “At 11:32 a.m., Mann Passed the Truck.” Everyone who’s read the story or seen the TV-movie released that same year, directed by Steven Spielberg from Matheson’s screenplay, knows what’s to come. The protagonist finds himself, improbably at first and then outrageously and then terrifyingly, in a battle with the unseen driver of a semi-truck.

By the time Mann defeats beast, you’ll have an experience not unlike most of us had a few years earlier with Hitchcock’s Psycho and a few years later with Spielberg’s Jaws–a reluctance to subject ourselves to the peril of being terrorized and killed in a little roadside motel, a lonely stretch of road or a tranquil-seeming beach.

Super-producers and directors of genre TV and films like Serling (who followed up The Twilight Zone with Night Gallery) and Dan Curtis (from the daytime drama Dark Shadows to numerous great TV movies like The Night Stalker) knew they could count on Matheson’s screenplays.

I’ve already lavishly praised The Night Stalker the influential January 1972 TV-movie directed by John Llewellyn Moxey from Matheson’s screenplay adapting Jeff Rice’s book. But enough can’t be said about Matheson’s other screenplays in the 1970s, including the sequel The Night Strangler and scripts for anthology films, with segments often based on Matheson’s original stories, including and especially Trilogy of Terror, written by Matheson and William F. Nolan and directed by Curtis.

Trilogy climaxed with an adaptation of Matheson’s “Prey,” published in Playboy in 1969 and included in the “Best of” collection. In the story, a woman brings home a statue, a totem of a killer doll.

Along with the doll, which wears a chain, is a scroll: “‘This is he who kills,’ it began. ‘He is a deadly hunter.’ Amelia smiled as she read the rest of the words.”

Would you smile? Maybe you would if you were in a Richard Matheson story.

But not for long.

Matheson continued to bring us his words for much of the rest of the next two decades. He wrote crime and horror and some of the most suspenseful tales ever to emerge from a typewriter, like Hell House, published in 1971, adapted to film as The Legend of Hell House. He also wrote a film, 1980’s Somewhere in Time, that is beloved by many who would not want to read tales of a mutated child or Las Vegas vampire.

That’s what made Matheson great, though. One year he could make us sweat with a story about a murderous truck driver, then turn around and give us a romance that transcended time.

The final words go to King, injecting a personal note in his 2013 tribute to Matheson: “He was a gentleman who was always willing to give a young writer a hand up. I will miss his kindness and erudition. He lived a full life, raised a fine family, and gave us unforgettable stories, novels, TV shows, and movies. That’s good. Nevertheless, I mourn his loss. A uniquely American voice has been silenced.”

***