Back in the early-1990s when I was writing for Vibe magazine, I met writer/editor Robert (Bob) Morales in the Lexington Avenue editorial offices. From the moment I saw him carrying a big box full of comic books and Black porn tapes (for research purposes, of course), I knew we would be friends forever. Bob was a few years older than me and had worked at various magazines including Heavy Metal and Reflex. Though I’d written a piece on Living Colour guitarist Vernon Reid for Reflex a few years before, it wasn’t until that autumn afternoon that our paths literally crossed.

Bob wrote a comic strip for the magazine that was illustrated by brilliant Kyle Baker and a decade later the duo created the Black-themed Captain America mini-series The Truth. For Vibe, he also did wide-ranging Q & A interviews with Robin Quivers, Toni Morrison and Vanessa del Rio, who he introduced me to when she stopped by to pick-up a few issues. Hanging in the offices of editor Rob Kenner or director of photography George Pitts (their spaces were our unofficial salons), Bob was an almanac of information about films, comic book creators, sci-fi writers (he had studied fiction under Harlan Ellison, was friends with Alan Moore and used to work as a personal assistant to author/ essayist Samuel R. Delany) and music.

Bob and I quickly became friends, which in turn meant I had access to his vast knowledge and cultural artifacts. When he discovered my weakness for all things noir and pulp, he began schooling me on various entertainments I needed to check out including the 1986 BBC series The Singing Detective, the NYPD novels of Jerome Charyn and the texts of Brooklyn, N.Y. born crime writer Donald E. Westlake along with the writer’s more famous pseudonym Richard Stark.

Under the Stark non de plume, Westlake penned the Parker novel series, documenting the iceberg of a man with no first name and his wild heists across the country. Although I was down with the crime texts of Chester Himes, David Goodis and Jim Thompson, I’d somehow missed out on Richard Stark. “I can’t believe you never read the Parker novels,” Bob sighed as he slid me a plastic bag stuffed with vintage paperbacks from his vast library. We were sitting on the 5th Avenue side of Rockefeller Center. “I had some duplicates, so I brought you a few.” Brother Bob was good in that way.

The name “Richard Stark” was enough to pull me in, but the writing is what made me stay. In the mid-1960s the “Stark” pen name was created so Westlake could write a different kind of book for the paperback market, which was believed to be the type of books men preferred. “All fiction starts with language, and I wanted the language stripped down and bleak, with no adverbs,” Westlake told an interviewer on 2000. “I want it stark. The Richard came from Richard Widmark.”

In the beginning he wrote the first three Parker books (The Hunter, The Man With the Getaway Face and The Outfit) in a year; the following year he wrote three more. In 2009 essayist Terry Teachout wrote, “Parker is as amoral as a loaded shotgun, a man devoid of introspection who lives solely in the present moment, never looking back and thinking ahead only far enough to plan his next job.”

Writer Elmore Leonard went on record saying that it was the George V. Higgins novel The Friends of Eddie Coyle (1970) that inspired him to switch from westerns to crime novels while serving as a literary guide down those grimy streets, but for many others it was Westlake/Stark books that taught them how to be lean and mean as well as planning a heist, kicking in a door and getting a character out of a jam quicker that you can say killer diller.

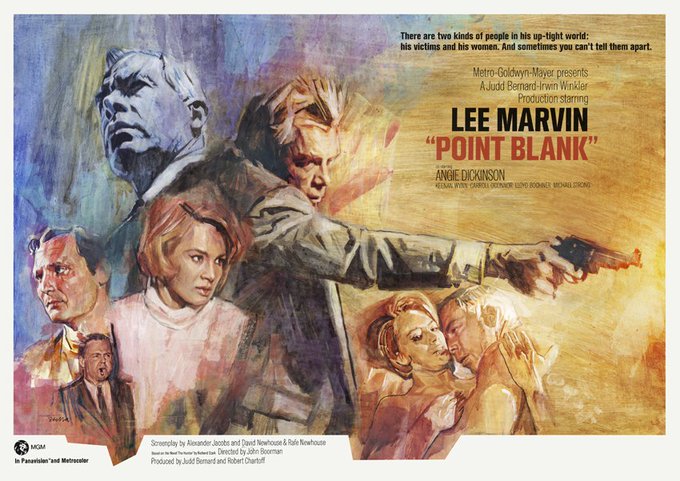

When my homeboy Bob handed me the Tower Records bag full of paperbacks, I excitingly looked at the cool covers and copy and soon realized that while I’d never read Richard Stark, there were a few films made from his books that I was familiar with including the brilliant neo-New Wave Point Blank, adapted from The Hunter, starring hard as marble Lee Marvin, and The Split starring hard as onyx Jim Brown.

The latter, released in 1968, couldn’t be described as a Blaxploitation film, but having Brown play a badass anti-hero planning to rob a stadium during a football game in that era was a bold move. With a cast that included Gene Hackman, Warren Oates and Ernest Borgnine, the final product overflowed with tough guy personas and swagger. While I’ve seen a photo of The Split on the marquee of my local grindhouse the Roosevelt Theatre in Harlem, I was only five in ’68, so I missed the first run, but caught it a few years later.

Meanwhile, Point Blank has been embraced as an American crime classic. “Point Blank is one of my favorite films because it’s a quintessential ‘60s L.A. gangster story,” says Cali-based crime writer (Ash Dark as Night) Gary Phillips. “The look, the color palette, criminals in stylish suits. He’s a lone operator up against the machine that is the corporate mob. Not looking to take it down, but get back his share of the money owed him from a robbery. The film was lean and spare, with influences of the (French) New Wave offering the viewer a looping back on itself narrative, the main character of Walker is defined by his actions.”

Though I never got a chance to see The Outfit in 1973 (I must’ve been on punishment that weekend), I clearly remember the exciting trailer with stars Robert Duvall, Joe Don Baker and Karen Black. In none of the movies was character ever named Parker on screen until the 2013 Jason Statham version directed by Taylor Hackford. ”Don never allowed Parker to be called “Parker” in any of the movies to guard against unwanted sequels,” Max Allan Collins wrote in 2013.

Still, when it came to the books, The Rare Coin Score (1967) is one of my favorites. The cover featured a stunning Robert McGinnis illustration depicting Parker as a mean, clean, fighting machine. “McGinnis’s cover for the 1967 Gold Medal edition of The Rare Coin Score features a Parker depiction par excellence,” wrote essayist Nick Jones in 2010. “Standing in profile, looking towards us but with his eyes ever-so-slightly averted, and with a sultry woman draped over him, the Parker on this cover is just so right. That woman (whoever she is – could she be Claire?) isn’t distracting him in the slightest; instead he’s fixed on something else – although not us, not quite. He’s thinking about the score in hand – because as we all know, when Parker’s working, working is all he cares about.”

The Rare Coin Score, the 9th book in the series, was hasn’t yet been adapted into a movie. As with most of Parker’s jobs, the heist was easy until it wasn’t. This one involved knocking over a coin convention inside a hotel in Indianapolis, Parker began getting sloppy when he decided to work with desperate men, rank amateurs and a dame, a hottie named Claire who became his gal for the rest of the series. But, after planning and plotting the coin heist, the set up began to unravel.

Stark doesn’t get into detail about the coins, but we just know they’re weighty and valuable. “I’m not a heavy researcher,” Donald Westlake told The New Black Mask in 1985. “It’s boring. I grew up plotting all sorts of heists. It may be that the writer is a failed crook. He has a more cowardly way to do it, you know: ‘Well, let’s just put it on paper.’”

Although I didn’t start writing crime fiction until years after first reading Stark, The Rare Coin Score put a spell on me that had nothing on Screaming Jay Hawkins. Still, my affection for the this loose change tale, which I’ve revisited several times over the years, goes beyond the book to a memory of a man I once knew in Harlem who had his grand collection of American coins swiped one sad day in 1978.

***

Reginald Lawson was the father of my childhood friends Darryl and Jackie. We had known each other since me and younger brother Carlos aka Perky were little kids playing in front of our building on West 151st Street. Like us, they lived on the first floor in apartment 1-H where we kids hung out constantly. Mrs. Lawson was sweet as honey and always welcomed us with open arms. Older teenager sister Debra, who had made me a fan of War’s groovy The World is a Ghetto album and had a poster of Wally Wood’s naughty “Dirty Disney” on her wall. She too was a sweetheart, though there was one afternoon when she couldn’t take anymore and put us all out.

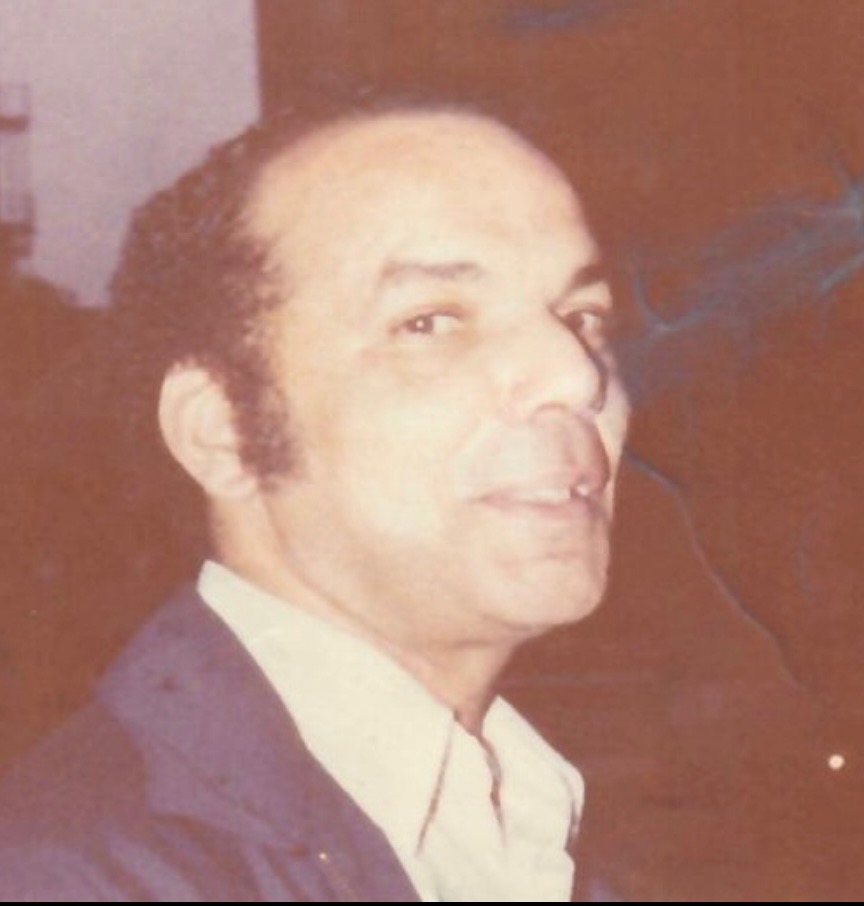

Poppa Lawson, whose wife called him Reggie, was a light-skinned, balding man who also had patience with the steady flow of children in his apartment. He was the only one of my friend’s fathers that I ever talked to on a regular. Other kid’s daddies were aloof and stand-offish, but Mr. Lawson actually took the time to listen and respond to us rugrats.

From the Darryl Lawson Archives

From the Darryl Lawson Archives

He once took the four of us to a Betty Boop film festival. As a nerdy comic book collecting, old school cartoon watching kid, I was no stranger to Fleischer Brothers animation courtesy of Popeye and Gulliver’s Travels, but risqué Betty was something different. Mr. Lawson was also a progressive husband, and more than a few times I watched him prepare dinner for the family; his specialty was meatloaf, which he topped with strips of bacon. “It adds to the flavor,” he assured me.

One afternoon I came to visit and Mr. Lawson, clad in black slacks and a dingy white t-shirt, opened the door. Their dog Prince had barked, but chilled out after being petted. “Hey Michael,” Reggie said as I walked in. “Hey Mr. Lawson,” I replied, crossing the room and sitting on the couch.

He called Darryl, who was in his bedroom, and went back in his chair at the dining room table. The table top was covered with binders and coins encased in cardboard holders and plastic. Picking up the coins, Mr. Lawson looked at them through a magnifying glass and jotted notes in a log.

“What are you doing, Mr. Lawson?”

“I’m going through my coin collection and writing in entries.” As someone who had a few hobbies that included a steadily growing comic book collection and buying records on a regular, I understood the collector sensibility. He had just bought a few new coins and was welcoming them into the family. “My father used to collect mostly American coins,” says his son Darryl. “Quarters, nickels, half dollars; he got most of them through the mail or from a specific store in midtown.”

It was 1975, I was 12-years-old and had been hanging at the Lawson apartment for years, but that was new to me. I knew Mrs. Lawson liked to read, especially gothic romances (artist Robert McGinnis did many of those covers too), but I had somehow missed out on the coins. Fascinated, I made my way to the table, sat down and just watched as Mr. Lawson proceeded through his process as through them no one else was in the room.

Indeed, he was completely absorbed, just as I would’ve been had I been reading the latest Jack Kirby comic. “Fellow hobbyists share something important to them which the outside world considers unimportant and frivolous, so that in a small all hobbyists are social outcasts,” Stark wrote in The Rare Coin Score. I couldn’t agree more.

Up to that day I never thought about collecting coins, but after seeing Mr. Lawson’s collection, all those silver pieces of various sizes and years, I began asking questions about where did he bought them, how were they cared for and how much were they worth. “He had thousands of dollars worth of coins,” Darryl recently recalled. “He always claimed he was going to one day sell them and buy us a house in New Jersey.” For 1970s Black middle-class New Yorkers, moving to Englewood or Teaneck, where there were cleaner communities and better schools, wasn’t simply part of the American dream, it was the Promised Land. When he was finished cataloging the coins Mr. Lawson returned the binders to the big closet positioned between the living-room and bedroom.

After seeing his collection, I started trying to collect coins as well. In those days when cash was king, there were still loose change circulating from the 1930s and 1940s. After buying candy bars from Jesse’s Candy Store (the owner was former jazz saxophonist Jesse Powell), Jesus’ Shop where I played pinball or the 155th Street corner newsstand where I bought comics, I always examined my change looking for a silver golden goose, that one coin that would worth some loot.

My devotion to coin collecting was short-lived as I got deeper into comic book fandom. At the same time, Mr. Lawson’s collection continued to grow. However, according to Darryl, his dad could often be too trusting with who he shared his hobby; sometimes, following a few after work cocktails, he might’ve talked about the coins as the nest egg that was going to be his family’s way out of Harlem, away from the graffiti covered subways, the head nodding junkies on Amsterdam Avenue and the sudden violence that could erupt at any time.

“My mom used to tell him, ‘Reggie, you talk too much about those coins to people who don’t need to know,’ but he never listened.” In the spring of 1978, Lord only knows who on the block or living in the building was taking notes, but one day Darryl came home from middle school and noticed something out of place that indicated there had been an interloper. “I just knew it,” he says forty-seven years later. After calling his mother at work, she instructed him to check the closet and, when he gazed on the top shelf, the coin binders were gone.

In those days few people bought apartment insurance or had their collections covered, and Mr. Lawson was no different. Though I wasn’t there when Mr. Lawson came home from work that day, I can imagine the devastating blow must’ve felt like a Muhammad Ali jab to the jaw, leaving him dazed and confused. “He felt really bad, because that was supposed to be our new house money.” The police were called, Darryl and the rest of the family were interviewed by detectives, but the coins were never found.

Discussing the robbery years later, Darryl and I went through a list of suspects who might’ve been criminal minded enough to pull it off. “The crazy part was we couldn’t figure out how they got in,” he says. “The door, the windows, nothing was broken.” Though that might sound suspect, the same thing happened to my apartment a few years later while I was sleeping and my roommate was in the shower.

Though he lost so much, Mr. Lawson never griped about the robbery as far as I heard. Darryl claims that his father didn’t change after the incident, but I believe I saw a difference. There were days when he looked troubled, as though the theft was heavy on his mind; there must’ve been times when he eyeballed his friends and neighbors suspiciously as he silently suspected one or another of stealing his prized collection. Awaking into a new, cruel world, the dream house was gone along with whatever complete trust he had in his fellow man.

While it’s been more than four decades since the Lawson coin heist, what in my mind has become The Silver Golden Goose Score, it has never faded from memory. Recently while writing a new Harlem neo-noir short story, I reread The Rare Coin Score and thought about Mr. Lawson. In the book the thieves talked a lot about finding the proper fence to sale the coins at a fair price and I wondered who Mr. Lawson’s coins were bought by; I doubt the seller knew much about their real value and were probably robbed themselves.

***

After completing 1974’s Butcher’s Moon, there weren’t any more Parker novels more than two decades. In his 2001 essay “A Pseudonym Returns from an Alter-Ego Trip, with New Tales to Tell,” Donald Westlake wrote. “In 1974, Richard Stark just up and disappeared. He did a fade. Periodically, in the ensuing years, I tried to summon that persona, to write like him, to be him for just a while, but every single time I failed. What appeared on the paper was stiff, full of lumps, a poor imitation, a pastiche. Though successful, though well liked and well paid, Richard Stark had simply downed tools. For, I thought, ever.

“It seems strange to say that for those years I could no longer write like myself, since Richard Stark had always been, naturally, me. But he was gone, and when I say he was gone, I mean his voice was gone, erased clean out of my head.” Stark returned two decades later with 1997’s Comeback.

These days I see a little of Richard Stark in so many things including the films of Quentin Tarantino and Steven Soderbergh and the graphic novels of Ed Brubaker/Sean Phillips and Brian Azzarello/Eduardo Risso. My longstanding favorite comic book writer/artist Howard Chaykin (Black Kiss, The Shadow) says his friend and editor Archie Goodwin handed him a stack of Parker books when he expressed a desire to write.

Novelist/editor Gary Phillips is another Parker fan inspired by Stark. “My O’Conner character, who appeared in Warlord of Willow Ridge, and now the upcoming The Haul, is my take, post-Parker as it were, of a professional thief who goes where cash can still be found in this world of crypto currencies. And like Parker, though my guy is Black, he just might not have been born with the name he uses these days. I give him more of an interior landscape than Parker, self-deprecating to an extent, but he too is taciturn and relentless in achieving his goals when he needs to be.”

In the winter of 1997, two months after the death of Mr. Lawson at the age of 70, Bob Morales and I went to see 65-year-old Donald Westlake at a reading that took place at Partners & Crime Books in Greenwich Village. This was around the time when The Ax was released, and though there was a modest turnout (I think it might’ve snowed that night), Westlake was in a great mood, did a wonderful reading and chatted with fans as we sipped bookstore wine. I’m pleased to report that the bespectacled, polite man I met that chilly was nothing like cold-blooded Parker.