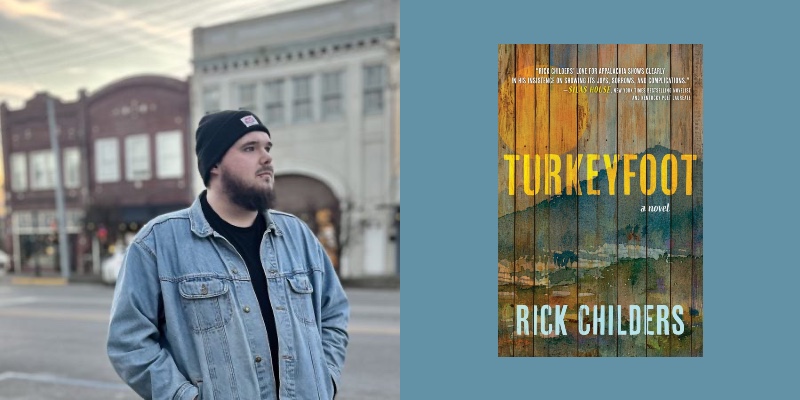

Not long ago I shared a table at the Kentucky Book Festival with Appalachian novelist Rick Childers, author of the excellent Turkeyfoot (Shotgun Honey Books, 2024.) At such events, it’s always good to be ready with a little pitch for potential buyers. Believe it or not, most of the people who saunter around the booths actually want you to pitch them your book. For my part, I refer to my novel as a historical thriller, “full of tension and eerie elements, a page turner, a pot-boiler, a hell-ride.” (Gotta move the merch, right?) I usually get the same responses, “Oh, that sounds good. My wife would like this.” Or, “Wow, my husband loves history. I’ll take one.” But Rick describes his book differently, and it elicits different responses. In fact, he plainly tells people that Turkeyfoot deals with the opioid epidemic in contemporary Appalachia.

Now that affects people.

I’d say there was a continuum of reactions to Rick’s “pitch” at the Book Festival. Some people gobbled up the book with no more to do about it. (“That sounds good, man. I’ll take one.”) Others wanted to know just how dark is the book, like, really? And then there was another set of potential buyers altogether. On hearing Rick’s honest description, they usually said something like this: “I’ve had experience with that stuff. Thanks for writing the book. It’s really important, but it’s not for me.” They set the book down and walked away. Eventually I asked Rick about it.

Without anger or disappointment, he said, “I get that all the time. It’s just how it is.”

Indeed, the opioid crisis affects thousands in the region, and well beyond. Families are destroyed. Lives are lost. Of course, we all know this, but few in the larger reading community have to confront it daily. It’s true also that writers of so-called “rural noir,” a sub-genre in vogue right now, often feature elements of the drug trade in their work. Dealers, users, and kingpins pop up all the time in these novels. But few writers navigate the complex human terrain as does Rick Childers. Turkeyfoot is unique for its look at how admirable people, noble people, good people, get drawn into things almost against their will. This sad and beautiful novel confronts the opioid crisis courageously, so much so that some people sometimes shy away from its truths. They are too close to it. They have to walk away.=

At the center of the story is Sweetie Goodins, a seventy-year-old drug dealer who exercises a profoundly negative effect on his mountain community in eastern Kentucky. He’s part of an enterprise that kills thousands, destroys relationships, and leaves families wrecked beyond repair. He’s contemptible, a rogue, a pox on the community, on humanity even.

But you know something? He’s lovable.

And as readers, we root for him. Yes, it defies all logic, but this is what so distinguishes Turkeyfoot. Childers manages to capture the complexity of the issue as it faces Appalachia. Turkeyfoot depicts the collective desperation borne of the drug epidemic. It portrays illicit trade in all of its pathos and horror. But things are never black and white. On the contrary, the book boldly exhibits the very complicated nature of things. In this author’s capable hands, readers can feel for Sweetie just as we do for his victims, most notably the nine-year-old Lucy Perley and her drug-addicted parents. In some of the most powerful passages I’ve ever read, Childers writes about his trapped characters and about the love that holds them together against the pestilence of addiction. It’s an achingly beautiful novel that simultaneously evokes the sadness and love that coexist in a mountain community.

I talked with Rick about Turkeyfoot recently.

McGinley: Hey Rick, thanks for doing this interview. I noted in the introduction above that the book deals with a serious issue: the opioid addiction in Appalachia. I also noted that your main character, the drug dealer Sweetie Goodins, is a sympathetic one. Can you talk a little about this character? Where does he come from? How does someone like Sweetie come to be?

Childers: Sweetie Goodins is a character looking two ways; he’s been raised in a rich traditional mountain culture, but he now lives in a broken contemporary version of the region that he has helped sow the seeds for. He’s not completely to blame, though. There are many men and women of all ages who become introduced to opioids because of injuries, health diagnoses, or other avenues. Once a body is introduced to such a powerful substance like that, some different things can happen. They become dependent on it themselves and some begin trafficking to support their own addiction. Or they simply see how valuable these pills are to folk and know it’s a quick way to make a living off something they don’t want to fool with anyways. There’s some great examples of this in Carter Sickels’ novel The Evening Hour. That’s Sweetie Goodins. He doesn’t want take any pills. He’s been raised on ginseng and raw milk. But he ain’t gonna leave a full pot on the table and his few relations to his community come through this exchange. I think that’s what’s more valuable than even the mighty dollar.

McGinley: Lucy Perley is a nine-year-old girl, the daughter of addicted parents. Was it difficult to write such a character, someone so much younger than you, a little girl born into something so dire?

Childers: I don’t think difficult is the right word. I knew Lucy so well I was very confident in writing her. What was odd was how others received her. Age was very confusing for many of my early readers. They didn’t understand how a girl so young could be so mature and engage with the world and people around her in the way that she does. We don’t consider how mature kids who grow up in these situations can act. Kids are so smart. It don’t take long for them to catch on. They’re molded by these environments, but they’re also still just kids. So why wouldn’t Lucy hold a conversation with a pill dealer she sees almost daily and then turn around to continue playing kitchen. That’s just life, man. Many of the precious babies who end up in these situations are broken in horrible ways, but many of them also grow into the grittiest individuals on the face of God’s green earth.

McGinley: The town of Turkeyfoot is almost a character in itself. There’s a sadness borne of (economic) poverty, in the derelict buildings, trailers, and parking lots where drug activity takes place. But there are just as many beautiful sites in and around town, in the hills and around the bodies of water. What is Turkeyfoot, the town? What does it mean as it’s represented in the book?

Childers: Well, literally Turkeyfoot is a conglomeration of places, people, and experiences I’ve fictionalized and added to over the past decade. In my head it’s like a big mash-up of Estill, Lee, and Madison Counties in eastern Kentucky. I chose the name because there was a pay-lake my grandpa and I used to go to at a real place called Turkey Foot, not far from where I live. I simply mashed the two together into one punchy word and it was what ended up sticking. I began doodling this little turkey track into all of my journals. That symbol reminded me of the Trinity and it gave me a lot of hope. Having a title and an image like that in mind can help keep you going as a writer. After that, Turkeyfoot slowly became more tangible in my mind and grew into the community in the novel. I have found a few friends in this life who truly appreciate the duality of our region’s beauty and decay. That’s what I knew I wanted to reflect in the novel.

McGinley: There are different types of drug dealers in this novel. There are characters like Sweetie, who remains friends with some of his buyers. But there are others, like Tim Stevens, who’s more concerned with profits than with the health of his clients or their families. What does the novel say about the drug trade in Appalachia and about how it affects different providers and consumers?

Childers: Well for folk who ain’t as familiar with it, I hope it just shows what an awful mess it all is. We could point fingers down the line and there ain’t hardly a one of us who couldn’t take some share of the blame. There are those who are more cynical and use that to numb themselves and I won’t even say I fault them for it. Others fancy themselves as anti-heroes and rebels; I witnessed the appeal of that as a young man myself. However, people end up getting pulled into this world and the further they wriggle themselves down the rabbit hole the more it hurts us all. We already have a lot of work to do. Writing has been so healing for me as an individual, for my family, and it revealed how hungry my community is for positivity surrounding this issue, as opposed to the latest mugshots and obituaries. That’s the work I’m excited about, helping the Lucy Perleys tell their story themselves.

McGinley: Why do you think the sub-genre we’re all calling “rural noir” is so popular now? Is there a danger in making art and entertainment based on a region’s problems?

Childers: Shew . . . that’s a good one, Chris. I cut my literary teeth reading regional writers. People and place are what drives the literature I enjoy, and thus I place a lot of significance in that as a writer. Once that identity piece clicked for me, so much of it made sense. Not just Appalachia, but authors like Larry Brown, Harry Crews, William Gay and so many others who were shown to me and their voices cut into my soul like nothing I had ever read. I say all of that to say this, that’s all I knew I was doing. I called it literary fiction. When I signed with our publisher Shotgun Honey, I suddenly found myself pulled into an entire new circle of writers – this whole crime fiction world that you know so well. It was a big shift for me, but as you know, the overlap is clear. Your question worries me quite a lot. I’ve turned it over in my head and heart since I began writing about life in this way and I’m still mindful of it. I was very careful to portray my characters and this place in a way that shows how much I love it. We have problems, but my goal isn’t to turn those problems into a plot point. It’s to heal as a community. I think part of the rural noir popularity is because of how viral true crime has gone. With that growing popularity many have recognized the pornographic tendencies intertwined with true crime’s identity so they choose to scratch that itch elsewhere and I can respect that. A genre of literature like rural noir or any other sub-category of Crime Fiction allows us to engage with these stories, tragedies, and hardships in a way that is still very real and meaningful without turning real, documented human suffering into fodder for Hollywood and the internet.

McGinley: Tell me about the process of writing Turkeyfoot. When did you conceive of it, and did you plot it out beforehand? How did you go about fleshing it out?

Childers: It took me a long time to write this book. I didn’t start writing until I started as an undergrad at Berea College. After sleeping through a lot of Chemistry I decided that path just wasn’t working. I had always been a reader and had taken extra English classes to avoid them in college. So of course, what do I do? I start taking more English classes. I had intro to Creative Writing with a professor named Anne Bruder and I wrote this short story about a pill dealer who had lost all of his connections so he was burning his home down for the insurance money.

A lot of my peers didn’t get it.

They were asking what a 30 or an Oxy was. But a poet named Jacob Anderson from North Carolina knew everything I was talking about and I discovered he had also written about pill dealers. His story was about exacting revenge on such individuals. Looking back to that dichotomy you mentioned earlier, Chris, this issue causes much emotion, and anger is a prominent one that people wrestle with.

From that point on I was mostly focused on the short story. I got to work with people like Crystal Wilkinson and Silas House and they breathed a confidence into me I had never experienced in my life. They believed in me. Around 2018 I was at the Appalachian Writer’s Workshop at Hindman Settlement School. (All writers should check this thing out and apply). That year I got to work with a writer from West Virginia named Marie Manilla. Marie strongly insisted that I turn the fiction pieces I was working on into a novel. And from that point on that’s what I did. It became Turkeyfoot. I mentioned how people and place are the driving factors in my writing so plot was honestly something that held me up for a long time towards the end of the novel. I had about two-thirds of the thing written, but had to take a step back and see how all of the pieces fit together. My friend Susan Berla made a suggestion that one character was very similar to two others so his scenes got split down the middle of the other two men and from there the plot started clicking.

McGinley: What’s next for you? What are you working on?

Childers: For the last year I’ve been lazy. I’m a slow writer. I trust my process and allow it to come to me. That gives it time to sit and simmer and the impurities start to boil out. The real thing starts to be all that’s left floating at the bottom of my cracked, cast-iron mind. In these down times I do sometimes write tidbits, poetry, and dialogue. Little things to keep my mind and tongue in the language of my stories; the people and their place. I am writing another novel that will be set in my hometown of Estill County, Kentucky. I’m excited to lean into my strengths and what I’ve learned writing Turkeyfoot, but I’m also planning to be a little weird and just let the writing be whatever the heck Rick Childers needs it to be when it comes out. We can always edit it later, right?