The heat and haze of summer days holds the power to rekindle memories of sacred childhood rituals—beaches and bicycles, playdates and popsicles, sandcastles and swimming pools—with all the urgency and unpredictability of a weather front. Such remembrances are often amplified by strategically timed seasonal reads, from lighthearted romances to dark-minded mysteries, which occupy coveted space on bedside tables and lawn chairs, some warming hearts while others send chills up down spines.

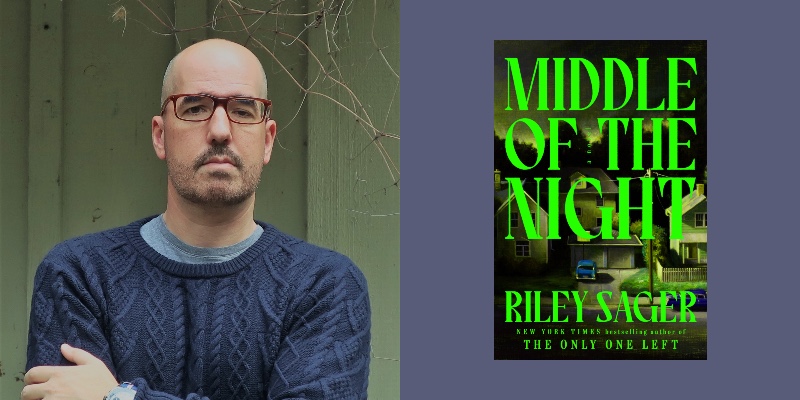

New York Times bestselling author Riley Sager—whose new novel, Middle of the Night (June 18, 2024; Dutton), is destined for vacation reading—has been the cause of sleepless nights for nearly a decade now. Since making his pseudonymous debut with Final Girls (2017), which won the International Thriller Writers Award for Best Hardcover Novel, he has become a global sensation with his books published in more than thirty languages. At least some of this success can be attributed to Sager’s unparalleled ability for taking familiar set-ups and storylines and then subverting them with fresh and fiendish twists.

Middle of the Night recalls just such a rite of passage gone wrong. In the summer of 1994, ten-year-old Ethan Marsh and his best friend, Billy, spend the night camping in his backyard. But when Ethan awakens the next morning, it’s to find Billy missing and the tent slit ominously from top to bottom. Thirty years later, Ethan returns to the suburban enclave of Hemlock Circle, which has largely existed in a state of stasis since Billy vanished. Haunted by the ghost(s) of his past, Ethan must finally confront the questions that still linger from that fateful event—even if doing so means exposing secrets that may be best left buried.

Now, Riley Sager divulges (some of) the tricks and treacheries of his trade …

John B. Valeri: Ten-year-old Ethan Marsh is deeply traumatized when his best friend, Billy, goes missing during a campout in his (Ethan’s) backyard. What are the long-term emotional and physical consequences of this event – and how did you balance using his condition to serve the story while also staying true to the underlying realities of PTSD?

Riley Sager: is a total mess. He’s wracked with guilt, suffers from insomnia, frets way too much, and is plagued by a recurring dream about the night Billy vanished. Because this has been going on for thirty years, he’s learned how to live with it. But when circumstances in his marriage force Ethan to move back into his childhood home, all those symptoms get worse, especially when strange occurrences start happening that suggest Billy has also returned—possibly as a ghost.

My editor is very good at forcing me to account for all my characters’ behaviors. Why are they acting this way? Why are they doing this and not that? That deep dive into their psychology then affects the plot. For Ethan, I made sure that the circumstances surrounding Billy’s disappearance—the things he said, the things he did, the things he didn’t do that might have saved his friend—informed his current behavior, making it realistic and logical when he starts to believe Billy is now haunting him thirty years later.

JBV: Hemlock Circle is an insular community that has changed little in the years since Billy’s disappearance. How do the dynamics of the neighborhood amplify Ethan’s distress – and in what ways does this setting serve as a closed circle mystery of sorts in establishing what happened to Billy and who was responsible?

RS: Yes, Hemlock Circle is very similar now to what it was like when Billy vanished in 1994. Part of that was simply for plot purposes. It wouldn’t be much of a mystery if no one from 1994 was still around. In fact, there wouldn’t be a book at all.

Since I knew most of the major players from back then still needed to live on Hemlock Circle, I decided to make it feel like a place where time stopped the moment Billy vanished. Because so much has stayed the same, the things that have changed really stand out. Who’s gone? Who’s returned? Among those who’ve always been there, why haven’t they left? Is it because they’re hiding something?

For Ethan, all of this messes with his head. He was gone for a very long time, so he feels a bit weird about suddenly returning. In some ways, he’s like a stranger in his own neighborhood. At the same time, though, everything is so familiar that he can’t shake the memories of thirty years. On Hemlock Circle, the past is always present.

JBV: The story alternates perspectives and timeframes, with Ethan’s present-day, first-person narration offset by shorter, third-person segments told through multiple POVs. Tell us about the appeal of this structure and its importance in revealing past events and personalities (as they were then). What was your process like to account for the intricacies of this set-up?

RS: While Middle of the Night is first and foremost Ethan’s story, it’s also about the community of Hemlock Circle. I wanted to give readers glimpses of the other people in the neighborhood, especially in the past. Since that’s hard to do in a book that only contains first-person narration, I came up with the idea for these third-person snapshots. Sort of “A Day in the Life of Hemlock Circle” that chronicles, almost hour by hour, the day leading up to Billy’s disappearance.

Those ended up being among my favorite parts of the book to write, because most of them include details that not even Ethan, our narrator, knows. As a writer, I love coming up with ways to show how the past informs the present, especially from a character standpoint. So these third-person chapters were a great way to show who in the neighborhood has changed, who’s stayed the same and, of course, who’s suspicious.

From a plotting standpoint, it was also a great way to drive suspense. The reader knows from the start not only that Billy vanished, but where and when. So as the book progresses, getting closer and closer to that place and time, hopefully the reader will be filled with anticipatory dread.

But while all of this was fun to write, organizing it wasn’t so easy. I go back and forth between being a detailed outliner and simply winging it. I used to outline religiously, but now it varies with each book. With Middle of the Night, the structure required intense outlining. There was about a three-month period in which the floor of my office was covered with index cards on which I’d written all the plot points and character beats. I was constantly staring at them, rearranging them, and just generally being a weirdo author trying to make it all fit together. It was a great day when, after figuring everything out, I finally moved the cards and gave that floor a much-needed cleaning.

JBV: Middle of the Night will resonate strongly with those who, like me, came of age in the 90s. In your opinion, what is the power of nostalgia – and how do you endeavor to capture those telling details that will evoke remembrances without letting them overwhelm the narrative?

RS: I knew from the outset that a chunk of the book would take place in the summer of 1994. Not only do I remember it very well, which helped cut down on research, but that summer had so many cultural touchstones that everyone who was around back then still remembers. Forrest Gump. The Lion King. Those weirdly popular CDs of chanting monks. Then there was the O.J. Simpson of it all, providing an undercurrent of darkness to an otherwise sunny summer.

Those references evoke very specific memories for a lot of readers, which really helps conjure up a sense of time and place. It was important for me to get the details right while at the same time not being too heavy handed with them. If you give too few reminders of what it was like back then, the time period gets lost. But if you provide too many, it starts to feel like a story about 1994 instead of one that partly takes place in 1994. After all, a little Speed reference goes a long, long way.

I find nostalgia fascinating because it’s so deceptive and often warps our view of the past. I think we’ve all experienced hearing a song on the radio that whisks us back to our childhoods and we feel all warm and fuzzy before realizing, “Wait a second. That period in my life was kind of awful. Why am I romanticizing it?” But that’s the magic of nostalgia, which I tried to use to my advantage. The plan was to get readers comfortable with references to Forrest Gump and Ace of Base before hitting them with the dark truth about what happened that summer.

JBV: Middle of the Night is one of those books that will have readers suspecting everybody at one point or another only to leave them looking back in wonderment at what was right before their eyes the entire time. How do you go about identifying the whos and hows of a story such as this – and what is your approach to then integrating clues and red herrings throughout the narrative to ensure fairness to the reader?

RS: Initially, the hardest part of writing this book was figuring out the answer to the main mystery: What happened to Billy? I went through so many possibilities, ultimately landing on one that I thought had the biggest impact. The tricky thing with twists and reveals is that they must be surprising while at the same time being satisfying, not just during the moment in which they’re read but also later, after readers have had time to digest them.

Once I knew what happened to Billy, the trick was threading the book with all the necessary clues while at the same time obscuring them enough that the answer is obvious only in hindsight. I think of each book as an elaborate mind game with the reader. Not to give away too many tricks of the trade, but I always try to have three levels of deception going at the same time. There’s the obvious, surface-level red herring that I suspect most readers see right through. Then there’s the slightly more complicated one in which I try to steer the reader toward thinking a certain way without letting them know I’m doing it. Underneath it all is what’s really happening, which very often is hiding in plain sight.

A gratifying moment for me with Middle of the Night was getting a text from a writer I respect and admire that basically said, “I did not see that reveal coming even though I should have because it was staring me in the face the whole time!” It felt very good to fool a pro.

JBV: Your books often incorporate formative experiences and/or cultural iconography – for instance, summer camp, hometown (sub)urban legends, the luxury apartment, and the haunted house. How do you continue to find inspiration in the familiar with each subsequent book – and what is the key(s) to then subverting that familiarity with a fresh take or twist?

RS: I love using things that come with an established set of expectations. We know the rules of horror movies, for example. We know how a haunted house novel is supposed to work. I like to follow these established ideas just long enough for the reader to think they know what they’re in for. Then I try to pull the rug out from under them by taking the book someplace completely different. Over the years, I’ve found that really leaning into certain tropes makes those eventual surprises land even harder.

Middle of the Night has two familiar aspects running concurrently. First is the concept of suburbia. Even if you didn’t grow up in the suburbs, you know from movies and TV what a typical idealized suburban summer is like. Bike rides and fireflies and ice cream trucks. I wanted to give readers a little taste of that before showing the darkness that was lurking underneath all that sunshine.

The second I-know-you’ve-seen-this-before aspect is the whole idea of a restless spirit urging someone to help solve the mystery surrounding their demise, which is what happens to Ethan. It’s a tried-and-true plot, done to perfection in The Sixth Sense. I tried to subvert it in several ways, starting with the fact that Ethan isn’t even sure Billy is dead. No one knows what happened to him. Since he vanished without a trace, Billy could be very much alive. Or it could be someone else playing a cruel prank. Or it could, in fact, really be a ghost. I think having that extra level of ambiguity is important. I want readers to feel as uncertain as Ethan does.

JBV: In the acknowledgements, you note that the creation of this book brought joy, frustration, and self-doubt. How did you work through the challenges of telling this story and what was your takeaway from its successful completion? Also, what words of advice or encouragement would you offer to others who may be having their own crisis of faith?

RS: This was a hard book to crack, for so many reasons. First, because it involves a missing child, I knew there had to be some reverence and respect in the writing. It couldn’t be a buckle-up-and-ride-a-roller-coaster thriller. The subject matter dictated a certain amount of seriousness and sadness. At the same time, it couldn’t be a depressing slog. There had to be some fun, spooky elements as well. That was a difficult balance to strike, and it took me some time to get there. More than I’m used to.

Speaking of time, I was also up against a very tight deadline. That always makes things more stressful, especially when a book requires extensive revising, as this one did. There was a major part of the book that just wasn’t working, and while I knew what was wrong, I couldn’t figure out how to fix it. After beating my head against the wall—both figuratively and, one time, literally—I realized the answer was already there in the text, patiently waiting for me to notice it.

Writing a book requires a certain amount of tunnel vision. But sometimes the tunnel gets so dark that you can’t find a way out of it. My advice is to not get so lost that you start to forget the big picture. If you’re stuck on something, usually the thing you need to get you across that finish line is already there in the characters you’ve created and the world you’ve built. All it takes is the clarity to see them.

JBV: Leave us with a teaser: What comes next?

RS: I’m keeping the plot of my next book under wraps for now, mostly because it’s very different from anything I’ve done before. All I can say is that it takes place entirely in 1954 and that it will be out next summer.