“We all have things happen in our past. We all have our burdens to bear. You can choose to allow all the bad things that have happened to hold you back, or you can choose to rise above those things and move forward.”

–Robert Crais

In Robert Crais’s thrilling, edgy, emotionally intense novels – twenty-four in all, twenty series books and four standalones, from 1987 to 2025’s The Big Empty – white knights come in many forms.

A meek chemical production engineer goes to extraordinary lengths to find the terrorist who killed her son in Nigeria. A cop sees his partner gunned down and, assigned to a K-9 unit because of his PTSD, makes it his – and his dog’s – mission to solve the murder. A UFO-obsessed podcaster aligns himself with an unlikely source to uncover a very real story of murder and corruption. A twenty-three-year-old skyrocketing entrepreneur risks everything she has to expose the family man she loves dearly. A spoiled L.A. wild child summons the grit and resourcefulness she never knew she had to expose a killer. A TV star, confronted with her unknown past, jeopardizes her entire career to see justice done. A Homeland Security special agent, forced to confront the fact that the rogue agent she’s been hunting is someone close to her, charges forward anyway. A bank official, compromised by the mob and fiercely protective of her family, determines to find a way out: “I will not lose who I am.”

All these, and many others, fill the pages of Crais’s books. Sometimes they are genuinely good people. More often, they’re just doing their best to surmount a difficult past and face an incomprehensible present. Their armor is dented, their hearts are sore, but they’ll be damned if they don’t do the right thing. If that’s the hill they die on, so be it.

But the most important white knights of all are the two who have become synonymous with Crais’s work: the wisecracking but driven private investigator Elvis Cole and his taciturn ex-cop, mostly-ex-mercenary partner Joe Pike.

On the surface, they could not be more unalike. Cole wears loud Hawaiian shirts, his office features Jiminy Cricket figurines and a Pinocchio clock with shifting eyes, his phone messages are flip – “Elvis Cole Detective Agency. We find more for less. Check our prices.” – and his manner is self-deprecatory. A sample exchange with a kidnapping victim’s best friend from A Dangerous Man (2019):

“What are you doing?”

“Thinking. Impressive, isn’t it?”

“Is this what detective work looks like?”

“Only when I’m showing off.”

“You’re funny.”

“A national treasure.”

Pike, however, is something else again. He speaks only when necessary, and when he does, it is only to convey the information needed. He does not joke. He doesn’t even smile. Every once in a while, the corner of his mouth might twitch a little; this is his equivalent of a belly laugh. Six-one, lean, all muscle, he dresses the same every day: faded jeans, Nike running shoes, a plain gray sweatshirt with the sleeves cut off, and government-issued sunglasses. On his arms, large red arrows tattooed on the outside of each deltoid point forward, a symbol that: “He would not retreat; he would not run away. That was the single immutable law of Joe Pike’s faith – he would always meet the charge” (The Last Detective, 2003).

Beneath the surface, though, the two men could be brothers. When they fall for a client, they fall hard, especially if that person is being victimized, and even more so if it is a family situation. “You always get in too deep, don’t you?” says a police captain to Elvis. “Always get too close to the client. Fall a little bit in love” (The Monkey’s Raincoat, 1987).

They both have good reason for that.

Elvis Cole never knew his father. When his mother was twenty-two, she ran away from home, and when she came back three weeks later, she was pregnant with Elvis – though he wasn’t Elvis then, he was Philip James Cole. “Jimmie,” and when Jimmie was six, she saw Elvis in concert, and changed his name the next afternoon. His mother did things like that.

The only thing she ever said about his father was that he was a human cannonball in a traveling circus. She may have been lying or delusional – neither was rare – but that didn’t stop Cole from running away from home repeatedly when he was a teenager to try to find him at different carnivals. Each time, his grandfather hired a private detective to bring him back. The old man was practiced at that – he used the same detective whenever Cole’s mother disappeared.

Pike’s childhood was even worse. When his father was drunk, which was often, he’d beat Joe and Joe’s mother, and by the age of nine, Joe had learned to take the hurt and fear and fold them into small boxes inside a locked trunk inside himself. “I will make myself strong,” he promised himself. “I will not hurt. It won’t always be this way” (L.A. Requiem, 1999). And it wasn’t. Pike grew big, grew strong and fast, and, at seventeen, joined the Marines, telling his father that if he didn’t sign the papers, he would murder him.

Vietnam followed, for both Elvis and Joe, where they learned to be lethal, and as Elvis tells a victim in The Monkey’s Raincoat, “I learned that I could survive. I learned what I would do to keep breathing, and what I wouldn’t do, and what was important to me, and what wasn’t. Just like you’re going to learn.”

After they got back, Elvis started his apprenticeship to be be a p.i. Joe joined the LAPD, a job he loved, but had to leave after three years, following a series of tragedies involving his partner, his partner’s corruption, his partner’s wife, and his partner’s death. Few people know the real story of what happened. Many cops blamed Pike for it. He let them. He had his reasons to stay silent. He was a white knight even then.

He took a contract job with a professional military corporation, and spent the next years doing jobs in Africa, the Middle East, South and Central America. As someone who knew him well back then explains to a skeptical policeman in A Dangerous Man, “Most of his contracts involved hostage rescues and recoveries and high-value-subject security….If you were held captive by, say, Boko Haram in Africa, or narco-terrorists in Central America, Mr. Pike is the man they’d send. He’s the man you’d want them to send.”

Now, he’s the owner of a gun shop, and Cole’s partner in the detective agency – mostly. He has been known to disappear. For weeks, sometimes….

Together, Cole and Pike have fought against international terrorists, serial killers, human traffickers, Delta Force mercenaries; corrupt cops, lawyers, politicians, and businessmen; and a profusion of gangs – Mexican, Japanese, North Korean, Serbian, Russian, Vietnamese, and New York Mafia. Some of the cases have gotten resolved by legal means, some by other forms of justice. As Elvis explains to a woman in trouble in Lullaby Town (1992), “Cops deal with the law. The law isn’t usually concerned with right and wrong. Ofttimes, there are very large differences.”

That’s why he pits two different criminal groups against each other in Lullaby Town, and again in Voodoo River (1995). Let them fight it out. That’s why the smug super-lawyer in Sunset Express (1996) suddenly finds himself trapped in the entirely different court of public opinion: “I will keep this alive until the DA finally builds a case or until you are driven out of business. I will haunt you like a bad dream.” That’s why an ATF agent in The First Rule (2010) gets the killer responsible for two murders – one a friend of hers, the other a friend of Pike’s – assigned to a particular prison: a long-term convict in there will avenge them both (“You have to take care of your own.”).

During all of this, Cole and Pike, with no family to fall back on, and so many fathers, mothers, sons and daughters heavy on their hands, work to put together their own surrogate family, characters that recur from book to book. Sometimes their roles are small, but key: LAPD’s Lou Poitras, “roughly the size of a Lincoln Continental,” who often has to bail Elvis out of trouble; Eddie Ditko, the phlegmy reporter who has “walked the crime beat for every dead paper in Los Angeles;” Frank Garcia, a Latin force in the community, whose daughter’s killer was caught by Cole and Pike, and who is now a crucial ally in the ranks of power.

And sometimes the recurring roles are not so small. The criminalist John Chen, “paranoid, needy, and burdened by less self-esteem than a grapefruit,” delights in helping Cole and Pike on the side, in exchange for information that makes him look brilliant (and, hopefully, land him women, though that part hasn’t worked out so far). Rough-edged bomb tech Carol Starkey, star of the breathtaking standalone Demolition Angel (2000) (see Essentials below), memorably blown apart and “stitched together like Frankenstein’s monster,” now helps Cole out from a variety of other departments, while wishing he would make a move on her. Jon Stone, former OCS, Airborne, Ranger, Special Forces Delta, and mercenary, and now a mercenary contractor, is happy to jump into action himself whenever Elvis and Joe need a warrior. He might complain about not being paid, but “Jon ate it up. Loved being a soldier, loved the company of like-minded men, loved the noise and the skills and the crazy wild-ass adventure lesser men feared” (Taken, 2012).

There is no surrogate family as important to Elvis Cole, however, as the one he hopes to make his real family. It is an arc that began in 1995’s Voodoo River, and has followed a tumultuous, heart-wrenching path ever since: Elvis’s rollercoaster love story with Louisiana lawyer Lucy Chenier and her son, Ben.

In Voodoo River, Elvis is in Louisiana because TV star Jodie Taylor, an adoptee, wants to find the medical records of her biological parents, and Chenier (an adoptee herself) is representing her in the state:

“Lucy Chenier was five-five, with amber-green eyes and auburn hair that seemed alive with sun streaks and a wonderful tan that went well with the highlights. She seemed to radiate good health, as if she spent a lot of time outdoors, and it was a look that drew your eye and held it.”

After the dramatic events of that book, they talk on the phone, each admits they missed each other, he hops back on a plane, sees a table set for two, is told Ben’s sleeping over at a friend’s, and to Elvis’s blank stare, she says, “Jesus Christ, what kind of lousy detective are you? Do I have to draw you a map?”

As the series progresses, they call, they visit, and she complains a lot about her ex, Richard, a wealthy businessman who keeps reinserting himself into her life, “and I do not like it.” When she’s offered a TV analyst job at an L.A. station, Richard himself warns Elvis, “You don’t think I intend to just let them leave, do you?” and when he fails in his attempt to poison the well at the station, he warns, “You think it’s over, but it’s not.”

Boy, is he right. By L. A. Requiem, Lucy’s living in Beverly Hills, and is a bit freaked out to hear how many people Pike has killed (fourteen). But nowhere near as freaked out as she becomes in The Last Detective (2003), that while she was away on business, and Ben was staying with Elvis, her son…disappeared. One moment he was on the patio, the next moment he was gone, and there’s a phone call to Elvis: “This is payback, you bastard. This is for what you did.”

“What did I do? What are you talking about?”

“I should have known this would happen,” she tells Elvis. Without getting into the details – you really need to read the book yourself – suffice it to say that: a) at one point, Ben is put into a large plastic box, and buried; b) it is all part of a scheme by Richard to bring Lucy back to him – until it goes very, very badly wrong.

Once it’s all over, and Ben is rescued, Lucy returns to Louisiana: “Ben needs to be with familiar people and places. He needs to feel safe.”

Over the next few books, they keep talking. The years pass. “I loved Ben like a son, and I missed him. We stayed in touch. I wish I had killed his father.” Ben is big now, a high school junior, Lucy is worried that Richard is writing to him from prison, Ben is chafing that Lucy is overprotective, that he’s not the boy in the box anymore.

Finally, their relationship having warmed back up, Elvis confesses, “I’m scared if we get back together, you’ll dump me again,” but, “I don’t want to be just friends anymore.”

Lucy replies, “I can’t change what’s done. I can’t pretend I won’t worry. I can’t swear I won’t kill you if you get hurt. I can’t even promise I won’t dump you. But I don’t want to be just friends anymore. I want to see you every day” (Racing the Light, 2022).

Is this too much detail on Elvis and Lucy? Live with it. By now, Crais fans had invested twenty-seven years with this relationship. We were all verklempt.

Will this all work out? Only time will tell.

Meanwhile, Elvis and Joe will continue to strap on their dented armor. There are lives at stake; evils to overcome; truths to be uncovered, no matter what the cost.

Always forward.

Meeting the charge.

***

Robert Crais always wanted to be a writer. Or make movies. Or something. Adopted at the age of five months by a family of Louisiana oil refinery workers and policemen, he ran around as a kid fooling around with his Super-8 camera and sending off stories that nobody wanted. He even ran off one summer when he was thirteen to join the circus (with his parents’ permission), where he worked as a barker and discovered a shocking thing about…the human cannonball. (Now we know where that came from). The explosion that shot him out was just an illusion! After Crais shouted that fact to the midway, the circus owners promptly kicked him out.

Finally, he decided to do the Responsible Thing, and enrolled in Louisiana State University’s School of Engineering, where he studied dutifully while taking writing courses on the side. The courses stuck, the engineering did not, and with only one semester left before graduation, he chucked it all away, packed his bags, and in the summer of 1976 at the ripe old age of 22, he headed out to L. A. to become a television writer. “It did not go over well on the homefront,” he admitted later, “as you can imagine.”

The other problem was…he didn’t know anything about television writing. He liked television, but he and his roommates were so poor they couldn’t afford a set of their own, so he’d go to department stores to watch the shows he admired, and make notes analyzing the episodes. Then he discovered a second-hand bookstore that sold old TV scripts for $2.50. He bought some and studied them intently, their structure and pace. How did they start? Was it an action scene? Break for commercial. How many scenes till the next commercial? And the next? Is there a cliffhanger at the end?

Finally, he wrote two spec scripts, one for Baretta and one for Baa Baa Blacksheep, and an agent agreed to submit them. “The Baa Baa people rejected the script,” says Crais, “but liked the writing style and asked me to write for them. The same day, the Baretta people called and told my agent that they thought the script was brilliant and wanted to buy it! It happened that quickly.”

From then on, it was an avalanche: Quincy, M.E., L.A. Law, Cagney & Lacey, Hill Street Blues (for which he was Emmy-nominated). There were a multitude of pilots, Movies-of-the-Week, even a four-hour NBC miniseries, Cross of Fire, about the rise of the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s, which the New York Times called “searing and powerful.”

He was making good money – but something itched at him. Everything he worked on was a collaboration, everybody’s fingers were in the pie. He wanted something that was all his. He escaped to a cabin and started writing, but his first attempts “were the worst. They were the Great American Novel. They were me trying to learn how to write a book. I didn’t have a story to tell. It was me typing.”

Then, in 1985, his father died. When Crais went back to Louisiana to help sort things out, he discovered that, after forty-five years of marriage, his mother “had never written a check, paid a bill, used a credit card.” Crais had to teach her how to do all that, “and I was mad, angry, confused. I thought I would write about it, so I could understand it.”

He started a book about a woman who comes to a private detective, desperate to find her missing husband, a man who had always taken care of every detail of her life, and now she was completely unable to cope. Crais modeled the detective a bit after himself, with his own worldview and sense of humor (and taste in shirts), and over the course of the book and its many revelations, the detective helps guide the woman, named Ellen Lang, into a true sense of herself, until, by the end of the book, she can look at the detective, Elvis Cole, and say, “I can do this. I can pull us together….I won’t back up. Not ever.” She’s even the one who shoots the main villain with Cole’s .38, holding the gun just the way Cole’s friend, Joe Pike, showed her.

He named the book The Monkey’s Raincoat, after a Japanese haiku, an agent sent it out, and…it was rejected by nine publishers, before Bantam bought it as a paperback original. It went on to win Anthony and Macavity awards, get nominated for an Edgar, and eventually end up on the list of the 100 Favorite Mysteries of the Century by the Independent Mystery Book Sellers Association.

Crais didn’t intend for it to be a series, but Bantam reminded him that they’d given him a three-book contract, so he kept on writing. People would come into Elvis Cole’s office, he’d take their case – sometimes against his better judgment – and at some point he’d call Joe Pike to come help out. It was the classic first-person detective novel style, and everybody was very happy with it.

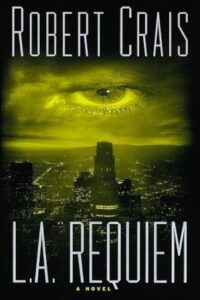

But then something started itching Crais again. In his sixth book, Sunset Express (1996), he wrote a prologue from a third-person omniscient perspective. Huh, he thought. In the next book, Indigo Slam (1997), he did it again. “I began looking for ways to expand what I was doing,” he said, “to combine different genres within the detective noir.” The result, L. A. Requiem (1999), hit like a bombshell. It was not only a detective novel, but a police procedural and a suspense thriller. It had multiple points of view, and flashbacks, especially into the unknown backstory of Joe Pike. It was a completely different animal, but Crais was so unsure of it at first that he told his agent, “If the publisher hates it, I’ll give the money back.”

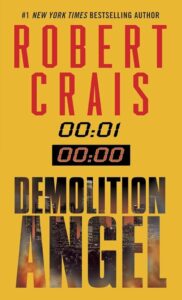

It became his most popular book to date (see more in Essentials below), and from then on, he let his imagination roam. Instead of writing another Elvis and Joe book, he wrote the standalone Demolition Angel after encountering the L. A. bomb squad while doing research for L. A. Requiem.

“I’d get calls from my editor asking how is the Elvis Cole book going…and I’d answer something like, ‘The new book’s really coming along.’” Finally, they needed to see something, “so I couldn’t keep it a secret anymore.” He sent 110 pages, his editor read them, and said, “This non-Elvis Cole you’ve submitted…” There was a long pause….”I think it’s the best thing you’ve ever written.”

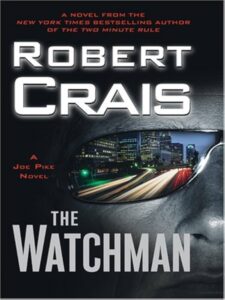

From then on, there were no holds barred. He followed Demolition Angel with another standalone, Hostage (2001), two more Elvis and Joe books, another standalone, The Two-Minute Rule (2006), and then, in The Watchman (2007), he broke new ground again. This was not an Elvis and Joe book, it was “A Joe Pike Novel.” Elvis was in it, but this time he was the one who got the call from Joe. The style was lean, propulsive, with no wasted words – it was not only about Joe Pike, it was Joe Pike, a distinction that would be matched by 2011’s The Sentry and 2019’s A Dangerous Man.

And when 2012’s Elvis and Joe Taken became Crais’s first #1 New York Times-bestseller, did he follow the obvious path and immediately write another Elvis and Joe? Of course not: The new book was about a man named Scott James and his dog, Maggie, both with PTSD, called Suspect (2013), and the love that book garnered led Crais to write his next book, The Promise (2013), about Scott and Maggie again – plus Elvis and Joe. Crais was unstoppable.

And then, on October 1st, 2019, two months after the publication of A Dangerous Man, a cardiac surgeon told him that he needed a quadruple bypass immediately, or he wouldn’t make it to the end of the year.

He was astonished. He was a runner, a hiker, a gym rat. He felt great! But the scans didn’t lie. Two days later, he had the surgery, and the recovery was long and difficult. “I wrestled for a time with the thought, ‘I may never write again.’ I went through a period where I thought, ‘I don’t wanna write again’….But, you know, time passed and I realized that I’m a writer. I get up every day, I write….Ten minutes a day became fifteen minutes a day became thirty minutes a day, became hours….I was on fire, and the book just rolled out.” That book was 2022’s Racing the Light, followed by January 2025’s The Big Empty.

His books have either won or been nominated for every crime novel award known to man, and he is the winner of the 2006 Ross Macdonald Literary Award, the 2010 Private Eye Writers of America Lifetime Achievement Award, and the 2014 Mystery Writers of America Grand Master Award.

Joe Pike would approve. Forward, always forward.

Meeting the charge.

___________________________________

The Essential Crais

___________________________________

With any prolific writer, readers are likely to have particular favorites, which might not be the same as anyone else’s. Your list is likely to be just as good as mine, but here are the ones I recommend.

That said – boy, did I have a tough time choosing.

L.A. Requiem (1999)

“Working a case is like living a life. You could be going along with your head down, pulling the plow as best you can, but then something happens and world isn’t what you thought it was anymore.”

In L. A. Requiem, that happens a lot, to everybody.

Elvis Cole thought he knew everything he needed to know about Joe Pike’s past. That was a mistake. Pike himself had taken the images of that past – “of his childhood, of women he had known, men he had seen die, and men he had killed” – and folded them up smaller and smaller until they had vanished. Now they have come roaring back to life. Meanwhile, Lucy Chenier has taken a deep breath, left her friends and home and job, and leapt into a new life in L. A. with Elvis. That does not go as planned, either. Everywhere around them, the ground seems to tremble and crack – soon, it will swallow someone whole.

A book about loyalty, friendship, honor, and death, filled with twists and revelations; a novel deeper, denser, darker than anything Crais had done before, L. A. Requiem will knock your socks off. This is the book Crais would like you to start with. Who am I to contradict?

Demolition Angel (2000)

“Starkey clawed open her purse for the silver flask, feeling the gin cut into her throat in the same moment she cursed her own weakness, and felt ashamed. She breathed deep, refusing to sit because she knew she would not be able to rise. She took a second long pull on the flask, and slowly the shaking subsided.

“Starkey fought down the memories and the fear, telling herself she was only doing what she needed to do and that everything would be all right. She was too tough for it. She would beat it. She would win.

“After a while, she had herself together again.

“Starkey put away the flask, sprayed her mouth with Binaca, then went back out to the crime scene.

“She was always a tough girl.”

Three years before, bomb tech Carol Starkey had died in a blast for two minutes, forty seconds, before being revived and stitched up, but her boss/ lover was not so lucky. Now, working for LAPD’s Criminal Conspiracy Section, she is scarred inside and out, physically and emotionally, and covers it all (badly) with booze and bravado.

What’s worse is that she’s now in charge of an investigation into another bomb blast, one that’s killed an old colleague of hers, Charlie Riggio. What’s even worse is that she’s been saddled with some big-foot ATF Special Agent out of Washington, who says he just wants to “help.” What’s worse than that – it looks like Riggio was targeted, and the bomb was set off by remote control. What’s worst of all – it may be the work of “Mr. Red,” a serial bomber obsessed with making the FBI’s ten-most-wanted list.

And that’s when things start to get really complicated. As the evidence slowly piles up, so, too, do the deceptions, lies, and betrayals. The ATF guy is not what he seems. Neither are some of her colleagues. And Mr. Red has a whole other game going, one he’s delighted to play with Starkey. If she has any hope of winning, she’s going to have to become a lot more than a “tough girl.”

This is a white-hot blend of thriller and police procedural, with an indelible lead character and terrific insight into police life.

The Watchman (2007)

“The very first notion that eventually became this book was this image I had of a young woman in a convertible. Her hair is flying because she’s driving really, really fast, hands on the wheel at 10 and 2, knuckles white, wind is screaming past her, she’s pretty, and her eyes are clenched closed.

“That’s all I saw, but what grabbed me was that here eyes were closed. Why? How did she come to this place? Who is she?”

–Robert Crais

She is Larkin Conner Barkley, 22, it is three a.m., and this is her magic hour – right until a Mercedes flashes in front of her, and she hits it. A man who was sitting in the back seat takes off, running hard down the street. The Mercedes speeds away.

“In forty-eight hours, she would meet with agents from the Department of Justice and the U.S. Attorney’s. In six days, the first attempt would be made on her life. In eleven days, she would meet a man named Joe Pike.”

Pike is there to pay back a favor Jon Stone did for him in The Last Detective. There have been three attempts on Larkin’s life in the past ten days, and Pike’s job is to take her somewhere safe. She is a lot, though: wild, spoiled, headstrong. After one escapade, he confronts her: “If you want to go home, let’s go. If you want to die, go home, then die, because I will not allow it.”

What follows is a hair-raising tale of drugs, money, terrorism, treachery – and resilience. Larkin Conner Barkley may seem like just another spoiled rich girl, but there’s more to her than anyone thought possible, least of all herself. Crais has always said he likes to create characters that rise above, that try to be better than they have been. The results of that in Larkin will have a dramatic effect on a lot of people in her life – as well as on Joe Pike personally.

___________________________________

Movie and Television Bonus

___________________________________

Television:

As noted, Crais had a great television career before turning to books. His name was not always found on the product, though. Episodes of Miami Vice and JAG bear the writing credits of…Elvis Cole. And one of the episodes of a 1983 CBS show I never heard of called The Mississippi was written by “Jerry Gret Samouche,” another of Crais’s registered pseudonyms. If you say it aloud, it is French slang for “I’m sorry this stinks.”

Movies – Elvis and Joe:

This is where things get more interesting. Crais has famously refused to sell the rights to the Elvis and Joe books for film. He wants his readers to imagine what they look like, as he himself does: “I can see their bodies, but their faces are always a blur…. Putting them in a movie would change everything. It would be called Elvis Cole, but it wouldn’t be Elvis Cole. It wouldn’t deliver what the books do the reader. And if something like that were done to Elvis, my fans would kill me.”

He tells a story, though: “When I was on tour for The Watchman, my agent called, gave me a phone number, and said, ‘I know you’re going to say no, but you should talk to this guy, you want to talk to this guy. He really wants to film The Watchman.’ So, me, I say, ‘What’s the point? The answer’s no.’ And my agent says, ‘It’s Jonathan Demme.’ Full stop. [Demme was the director of such films as Melvin and Howard, Stop Making Sense, Philadelphia, The Silence of the Lambs, and Married to the Mob] So I called Mr. Demme, who was absolutely wonderful. Loved Joe Pike. Loved the book .Wanted to make the movie. We talked for something like an hour and a half. My answer was still no, but we swapped numbers and stayed in touch.

“Every time I had a new book out, Jonathan would call, we’d yak a while, and he’d ask if I’d changed my mind about The Watchman. Jonathan passed away in 2017. Every once in a while – not often – I think to myself, man, I would’ve loved to see that film.”

There is also a 2011 article online from a site with the name It Rains…You Get Wet, which is pretty hilarious.

It presents as a retrospective of the Elvis and Joe film series, launched with the surprise success of 1991’s The Monkey’s Raincoat, starring Kurt Russell as Elvis and Sam Elliott as Joe. The same pair appeared in the movie adaptation of Stalking the Angel, retitled Stalking the Yakuza, but by then there were rumors of trouble brewing between the stars (“Joe’s got a bigger gun than I do,” “Cole gets more lines.”). So when Lullaby Town, rechristened New York Dreams, was filmed, a new duo took over: Robert Downey, Jr. as Elvis, and Val Kilmer as Joe. “To say it was an unmitigated disaster would be kind,” notes the piece. “What had to be the most lasting and hated symbol for Crais aficionados was this shocking revelation from the film: Joe Pike’s nipple ring. It still makes my head hurt to envision it.”

Retooled on a tighter film budget, the next one, Free Fall, was scripted by John Milius and directed by William Friedkin, and starred Eric Roberts as Elvis and Jeff Fahey as Joe. The writer of the piece grudgingly admits that “it was better than you’d expect from that duo,” but “don’t get me started on the casting of Lucy Chenier in that Voodoo River monstrosity….”

Movies – The Standalones:

Back in the real world, Crais did have no problem selling the rights to his standalones, however. Demolition Angel went to Columbia/TriStar in 2000, with Crais as the scripter. In 2014, Suspect went to Fox 2000, to be produced by Nina Jacobson and Brad Simpson, the producers of the Hunger Games franchise. In 2016, The Two-Minute Rule ended up with two entities working together, Original Films and Story Mining & Supply, with a Shameless writer adapting. I don’t know what’s happened to any of them.

The only Crais novel to actually see the screen was 2005’s Hostage. One reviewer of the book wrote that it was “like watching a Bruce Willis movie,” and, sure enough, Willis and his company pre-empted it, with Crais as scripter. Says Bob:

“I wrote the original screenplay and the rewrite, which Bruce and the producers all liked. Somewhere in the mix, studios changed…[and] it was a very complicated business. With each evolutionary change, new people would come in, with new screenwriters, new directions, until [director] Florent Emilio Siri came along, and he had his own viewpoint. It ended up being changed in many ways. The book is very small, claustrophobic, and intense…[and] suddenly Bruce is crashing cars and everything. They lost the focus of the story. If you look closely at the credits, you’ll notice I don’t have any screenplay credit.”

On Rotten Tomatoes, the movie has a Tomatometer score of 35%. Crais tells of one cop who came up at an early book signing and said that Hostage would make a good movie, but “they’d probably mess it up,” though that wasn’t the word he used. Years later, they met at another book signing. The cop gave him a knowing look, and said, “Told ya.”

___________________________________

Personal Bonus

___________________________________

Here’s a good place to note that I myself was Bob Crais’s editor for five books, from 2011’s The Sentry through 2017’s The Wanted. We originally met in 2006 at Florida’s Sleuthfest crime conference, where he was their featured guest, and we gabbed and shared a meal. I’d been a fan of his ever since The Monkey’s Raincoat – in fact, many of the references used for this piece are from the old paperbacks I pulled from my bookshelves – and so when the opportunity arose a few years later, I was delighted to actually become his publisher, and, in 2014, to accompany him to the Edgars where he was named the Grand Master.

Throughout the time we worked together, he was just the most charming guy – warm and funny and happy to share a story. He was also a meticulous craftsman, the very definition of a planner, not a pantser. Every book was heavily researched and outlined, his office walls covered with cards stuck to foam boards, notes and ideas about scenes and characters and settings. If it popped into his head, he stuck it on the boards. He liked to see it laid out in front of him. Sometimes it was just an image – the woman speeding along the road with her eyes closed in The Watchman; Elvis alone in his house with just his ornery cat in The Wanted, and the single line: “I don’t have kids, I have a cat.” Emotional harpoons.

Once he felt he had it all – beginning, middle and end – he started writing. And rewriting. And rewriting some more. “I obsess,” he admits. And sometimes that’s a problem when you’re on a hoped-for book-a-year schedule. The book’s been sold into the stores, the co-op’s been all set up, the publicity and tour are all in place…but the book’s not done yet.

Notes started popping up in the Acknowledgements pages: “The Putnam production team went above and beyond to make this book happen. The author apologizes for jamming their time line” (Taken); “Neil Nyren and Ivan Held [my boss] could not have been more supportive; they almost certainly believe I am disordered. Not without reason” (Suspect). One time, he send a final set of revised page proofs directly to my house on the weekend, and I promptly called my managing editor, who ran across town personally to pick them up, so she could then hand-correct the page proofs she already had, and send them to the plant. It was hairy – but worth it. Thanks again, Meredith.

And thank you, Bob!

And now, one final story:

___________________________________

Stan Lee Bonus

___________________________________

Among the unproduced pilots that Robert Crais wrote in his television days were two for The Amazing Spider-Man and Dr. Strange. It meant a lot to him because he had been a huge Marvel Comic fan when he was a kid, and had even won a prize from Marvel for a letter of his they published in The Amazing Spider-Man – to be more accurate, it was actually, a “No-Prize,” one of the joke awards Marvel gave out in the 1960s.

“It’s actually just an empty envelope they mail to you,” Bob said in an interview, “but I have to tell you, that’s one of my prized possessions, believe me. So when I first got the call about the pilots, an executive at Warner Brothers asked me to come meet Stan Lee. I immediately ran around the house screaming, hunting for my No-Prize. Now comes the day of the meeting, and I arrive at this lovely restaurant. There are a load of suits in their Armani jackets, and I’m there trying to look like an adult, when Stan Lee walks in. “Mr. Lee, this is the writer we’ve been talking about, yada, yada, yada, and in the middle of all this, I whip it out, and say, “Stan, look at this. I got a No-Prize!” and asked him to sign it.

“Stan was thrilled! All these executives are sitting around asking, ‘What the fuck is going on?’ And I look at them and say, ‘Hey! This is a Merry Marvel Marching Society No-Prize!’ They were just oblivious, not a clue, and Stan and I are cackling like two loons.

“No matter who I am, or what I do, that No-Prize mans so much to me. It is the real me, addressed to Bobby Crais at my Baton Rouge home address. It’s framed and hangs in my office.”