When I first trial-ballooned the idea of writing a fantasy murder mystery to a few other writer friends, the concept was met with a little skepticism: Could be really tough! Murder mysteries need people to know exactly how the world works. With fantasy, you can do anything, so it’s hard to build a mystery out of that.

I knew instantly that this wasn’t so. Fantasy magic works only when the audience knows exactly what it can and can’t do: that’s a core thesis of worldbuilding. But more to the point, I knew that a fantasy murder mystery had been done before – and had been so successfully that it had become a cornerstone of entertainment culture.

The first four Harry Potter books always focus on a series of mysterious crimes taking place within a tightly contained environment, with some of the crimes producing bodies (though not dead ones, just magically paralyzed ones). The mysteries always follow very tight, specific beats: there are clues built up during the start of school, and then more are carefully released at very predictable events after, like sports games, holiday parties, Christmas breaks, and exams. There are suspects, revelations, theories, and often a smaller set of crimes that the detectives confuse for the larger threat. All of it builds to a grand confrontation where the secret villain is revealed to have been present the whole time.

Sound familiar? It should! Because this is more or less the bones of a classic drawing room murder mystery. For example, in At Bertram’s Hotel, Miss Marple takes a two-week holiday in a inn where the staff and the guests prove to be more than they seem – much like the teachers and students of Harry Potter. A contained environment, a series of odd incidents, a crime: it’s all there.

The reasons fantasy murder mysteries work is because the two story types are oddly symbiotic creatures, with each one having demands in the exact places where the other genre doesn’t. For example, murder mysteries are one of the few genre types that has a specific plot requirement. Just like how a romance must feature the protagonist getting together with someone at the end – a romance writer will quickly tell you this has to happen, otherwise it’s not a romance – a murder mystery must end in revelation, the classic “whodunnit?” Besides this, murder mysteries are completely free to be inventive, and can take place anywhere and feature nearly anyone.

Fantasy stories, however, have no specific plot requirement. There is no default fantasy plot. There’s the vague expectation of a big battle here or there, and a few old tropes about the country farm boy being revealed to be the chosen one and then something something grand quest, but fantasy moved beyond the basic Joseph Campbell archetypes a great while ago.

What readers really desire of fantasy is a sense of place: to be introduced to a setting and characters that are both familiar and strange, existing in a world with its own histories, restrictions, opportunities – and grudges. In other words, often the same sort of stuff you have to build into a murder mystery. The two complement each other tremendously, really: for while fantasy often examines class, power, and ideological struggle, murder mysteries do precisely that as well. The costumes are just a little more ostentatious.

Perhaps the one place where murder mysteries and fantasy diverge is a sense of the scale of threat. Fantasy readers like big places, big powers— and big destruction. It’s not just that the armies have to be big, but entire kingdoms, realms, and cities must also potentially be destroyed, or at least damaged during the proceeds of the plot. Murder mysteries are much smaller in scope: a great wrong has been done, true, but it is usually only one death. We are then driven to unwind this tangle of human impulse and desire in order to determine the culprit, which can be dangerous… but is unlikely to result in the fiery holocaust of an entire continent.

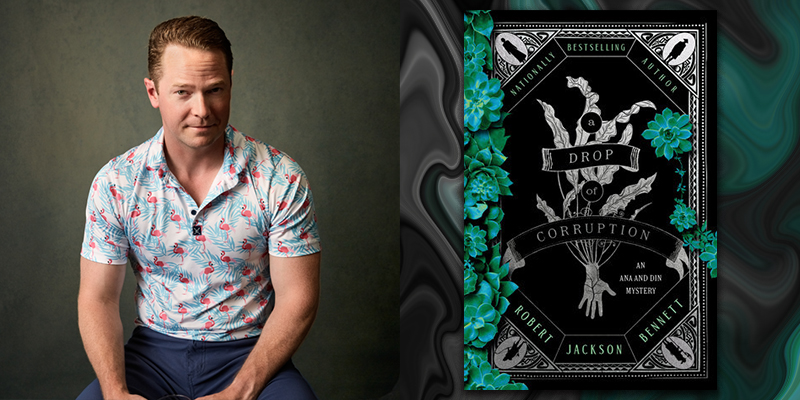

As such, it is perhaps surprising that the world of The Tainted Cup and A Drop of Corruption both focus so steadfastly on these very human and small-scale conflicts—while the true, enormous, civilizational threat occurs in the distance.

For each wet season, the seas to the east of the Empire churn, and giant leviathans emerge and try to breach the sea walls to go wandering and raging, leaving death in their wake. Each year, all the arts, genius, and resources of the Empire must be mustered to keep them back—often with great loss of life.

The detective Ana Dolabra, and her assistant—our protagonist—Dinios Kol, however, do not battle these leviathans. They do not wield immense weapons and go lightly dancing up the limbs of these great beasts to strike at their hearts in a tremendously cinematic sequence. Rather, Ana and Din are tasked with the maintenance law and order in this land that lives with such anxieties floating over it every year.

It seems a curious choice, I suppose, to take a world of such huge stakes and instead focus on the small things—yet fans of murder mysteries may quickly recall another mystery story that does this as well.

In Anthony Horowitz’s World War II television show Foyle’s War, Detective Chief Superintendent Christopher Foyle dearly wishes he could join the front lines and defend England from threat of invasion, but is instead forced to remain a humble Hastings police officer, and pursue petty crime. Yet in an era of so much struggle, there really is almost no such thing as petty crime: each instance of profiteering, black market trade, and murder often come with profound consequences that could endanger nearly any aspect of England’s defenses. Often these crimes get mixed up with military operations, and plots of conspiracy or treachery, leading Foyle into messy moral thickets that make him doubt how his nation is prosecuting this war for their very existence. Yet he strives on, performing this act of service that seems small, but portends a grander conflict.

Because what Foyle is really battling is not a handful of murderers, but a battle for the soul of his nation. A civilization that lives under so much threat is liable to unravel, leading to corruption, suspicion—and collapse. To prevent this, and to keep an England worth defending, the morally upright, stiff-necked Foyle chases after criminals both large and small, and keeps the peace during an era of war.

In this manner, the stories of The Shadow of the Leviathan and Foyle’s War have much in common. Both ask the questions—how can we keep this up, and retain our civilization? How can we ask our people to follow the law when they are so exposed to lawless violence? How can we maintain our humanity while living under this constant stress?

This is where the meat of the story lies: not in magical mass destruction, but in what we do to each other when we feel the rules are getting fuzzy, and what steps we have to take to reassert the law—and why. As Ana and Din travel the grand and holy Empire, and see how all the human frictions and resentments imperil their yearly fight in so many ways, they’re forced to wrestle with these questions again and again.

I hope it makes for a grand entertainment, while also giving those of us living in this particular reality a little food for thought.

***