Roberto Saviano has lived in hiding for over a decade. His first book, Gomorrah, was an astonishing, wide-ranging portrait of the Camorra, the immensely powerful crime organization that rules Naples. Saviano, a young Neapolitan journalist then, filled the book with details, dates, names and nicknames. The book became a best-seller, and Saviano became a target.

But he’s never been silent. While under constant guard, Saviano has become a crucial voice in Italian politics, speaking and writing about corruption and crime. His attitude is a cross between by any means necessary and what do I have to lose? He’s described life under protection as “tragedy” and “shit,” and yet he’s never expressed regret. Instead, he keeps writing about organized crime.

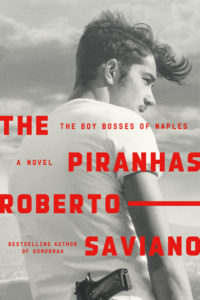

In The Piranhas, newly and brilliantly translated by Athony Shugaar, Saviano turns from the entrenched systems of the Camorra to Naples’ newest criminals, packs of teenagers called paranze. The Piranhas is a portrait of one paranza, founded and led by an ambitious, impatient fifteen-year-old named Nicolas Fiorillo. His understanding of crime and masculinity comes from his native Naples, the Italian Mob film Il Camorrista, and hours watching Breaking Bad—which is enough, it turns out, to start a gang.

I interviewed Roberto Saviano about The Piranhas over email, through several intermediaries. He insisted that we discuss the novel only as “fiction about real events”—fully reported, except the characters’ inner lives. The result is a deep, disturbing portrait of human nature. Saviano has no heroes or antiheroes, no neat arc. Just real kids, shooting real guns. You’ll hear the shots echo long after the book is done.

Lily Meyer: In Gomorrah, you vividly described the Italian media’s cluelessness in covering organized Neapolitan crime, concluding: “Media coverage is only concerned with the aesthetics of Neapolitan slums.” Now that you’re writing about Naples again, what responsibilities do you feel toward the city? Toward your characters?

Roberto Saviano: My point of view about organized crime has not changed, although 12 years have passed since Gomorrah was published. I still believe that the mainstream media approaches criminal matters in a folkloristic and superficial way, rather than describing the economic forces behind them. Take Gomorrah the TV series, which became a landmark for whoever wants to describe crime mechanisms in Italy. Often, you’ll find newspaper headlines like “Criminals rob like in Gomorrah,” “Gomorrah-style ambush,” or “Gomorrah-style murder.” Clearly, the criminal actions described in those newspapers existed before Gomorrah and will exist afterwards, but Gomorrah allows many journalists to explain events more clearly. It’s become shared, inherited information.

I have never really stopped writing and talking about Naples, and I always feel a responsibility to depict my characters the way they are, meaning people just like us. What interests me is making the reader wonder whether he or she is really different from those characters, and if the answer is yes, the following question should be: why?

LM: You start The Piranhas by telling us, “What you are about to read actually occurred.” Do you want The Piranhas to be read as fiction or nonfiction? Do you care?

RS: It is very important for me that The Piranhas be considered a fiction novel about real events. I took the liberty to describe how the protagonists of my book feel. Everything they do really happened, and everything they feel is described as a result of years of studies. But I didn’t want to miss the opportunity to describe the human ferocity of ordinary kids who, after shooting immigrants for target practice, go back to sleep in their cozy little rooms.

LM: In other interviews, you’ve said you researched The Piranhas by attending trials and reading court records. How did you turn those trials and records into fiction? And how did you find the right narrative voice for this book?

RS: Court records have a huge narrative power. Testimony during trials, too, and wiretaps and bugs. The way the judges handled the stories of these very young kids gave me the seed of the story. The same happened with Gomorrah —book, film and TV series. I always thought that the goal is to translate into a language for the masses what is technically comprehensible only to the insiders.

LM: Which is most important to you: character, plot, setting, or sociology?

RS: I could say that sociology is the element that shapes my work more than anything else, and I could add that the setting has to be Naples because I know everything about it and because it’s the open wound through which I can see the world. But it’s not exactly like that, actually, because if the sociologic aspect were my guiding star, perhaps I would have a more paternalistic attitude, which I am not able to have and is not part of me.

LM: The Piranhas seems consciously anti-drama. There are no huge climaxes, and the murders and big heists are brief and dry. (Which is not to say the book is dry! It’s completely compelling.) Why did you want to steer away from drama?

RS: Because reality is exactly how I describe it. Criminal actions, murders, ambushes are not epic at all. They are immediate, fast, at times ridiculous. For me depicting this aspect is fundamental, because nothing is heroic in organized crime.

LM: The role of TV and movies—especially Breaking Bad—is huge here. At one point, Nicolas feels like he’s “writing the screenplay of his own power,” and when the paranza commits murder, the victims seem unreal. What do you think is most real to them? In other words: when are they acting, and when are they living?

RS: That’s exactly the point: criminal organizations live off of the stories that are told about them. The more epic and brutal the story gets, the more power they have. That’s why their actions are like demonstrations, used to build a frightening storytelling, which freezes whoever thinks of overturning the system that they impose on the territory.

That’s exactly the point: criminal organizations live off of the stories that are told about them. The more epic and brutal the story gets, the more power they have.The young Mexican narcos, just like the piranhas in the Neapolitan neighborhoods, spread fear through acts of pure and unpredictable violence, which makes them invincible. The message is: no one should feel safe. No one, nowhere. As a result, life becomes acting; there is no life without a role to play. Even the moments that should serve as a final break from fiction—I am thinking of bloodshed: the death of a companion, of a brother or a son—even those moments, instead of serving as a sudden and brutal return to reality, make the stakes go higher and the role to play becomes even more important. In moments of crisis they go from supporting actors to protagonists, but never abandon their role.

LM: One of The Piranhas’ most moving and disturbing episodes is the chapter when Nicolas punishes his friend Drone by demanding oral sex from his sister, Annalisa. It’s one of the only times the novel goes into a female character’s head. How did you get to that scene?

RS: The story of Drone’s sister is grotesque, because it clearly shows the superficiality of the Piranhas in managing matters that are usually at the top of people’s list of values. Using sex to play, to punish, and involving in that punishment an innocent person feels inhuman and incomprehensible. But Drone’s sister seems to be perfectly aware of the power games of the criminal gangs. Despite keeping a distance from the Piranhas, she proves to be part of the context that fed the thirst for power of that “school of fish.”

LM: How has The Piranhas been received in Italy, and especially in Naples? What impact has it had on boys like Nicolas and his real-life paranza?

RS: The reality of the paranze is as relevant as ever in Naples: readers recognized the daily life of entire neighborhoods in its pages. Some of the paranza kids asked, through their attorneys, to meet me. The police officers who work on the streets know stories like these, and try to fight them every every day with poor resources. Many mothers wrote to me to let me know that what I wrote about failure is true: teaching your children to fail is fundamental because the risk is that in order to win, in a land that lacks opportunities, the only way possible is crime. Teaching to fail means giving your kids the certainty that there is not only one occasion to make it, but infinite ones, and a whole lifetime to try.