I have long had a love affair with the Ohio River Valley of my youth. I grew up believing it to be a special place and home to steel, grit, and men both hardened and blackened by the fires of the mills.

My first-grade teacher, Mrs. McIntire, reinforced this belief by assuring us that when the Soviet Union nuked the United States, our valley would be the first target as the communists would want to destroy our steel mills. While this was unsettling to my seven-year-old self, I was eventually reassured that we would be safe when we did our bomb drills, and I would huddle in our coat room, my head between my knees, snuggly protected from a nuclear attack.

When I was growing up in the sixties and seventies, there were sixty-thousand steel mill jobs along a twenty-five-mile stretch of the Ohio River, reaching from Weirton, W. Va., downstream to Martins Ferry, Ohio. There were also glass factories, potteries, and coal mines.

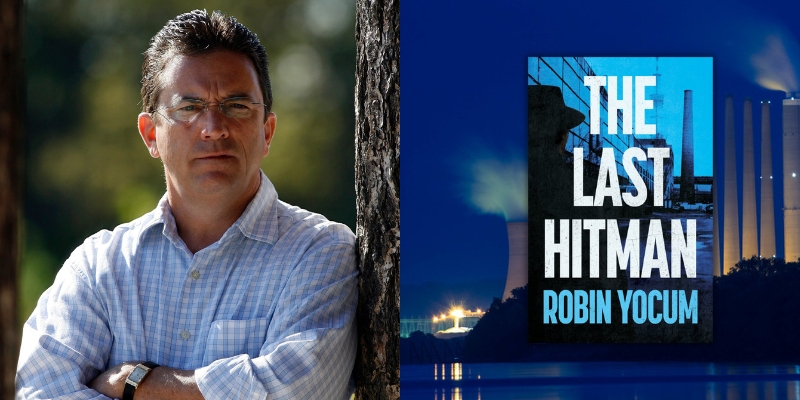

This is the Ohio Valley that I try to capture in my novels.

The Ohio Valley rocked. Steubenville, Ohio, and Wheeling, W. Va., were the commercial hubs. Businesses thrived amid air pollution that sometimes caused streetlights to burn at noon. There was a din in the narrow straits between the hills, an omnipresent grind from the roar of the mills, the groan of coal trains, and the whine of trucks. The mills belched smoke and fire, and the Pennsylvania Railroad yards in Georges Run and the Nickel Plate yards in Dillonvale were jammed with coal cars that would feed those flames.

Steubenville was a wide-open town. The Youngstown mob controlled the whorehouses on Water Street, the gambling, and the loansharking. I could get football parlay sheets in my high school. Gambling was so commonplace that I’m not even sure I knew it was illegal.

My grandmother would stop at Lane’s Lounge in Mingo Junction and play the daily number. I was too young to understand what was going on, but my recollection is that the only things on sale in the lounge were newspapers, cigars, and chewing gum. Of course, Louie Lane was taking bets and making his money on the vig.

Everyone knew that, and no one cared.

The mills were the financial anchors and home to the toughest men on the planet. My father worked at Weirton Steel. There were days when he would come home black with soot, the only white visible was his teeth and the perfect circles around his eyes where his suction goggles had been. He would shower, and Mom would follow him into the bathroom with a can of Drano.

The grit that erupted from the mills and power plants covered everything, and that’s not an exaggeration. If you washed your car on Friday night, on Saturday morning you could write your name on the hood in the fly ash.

After we finished our grass drills and calisthenics during morning football practices, when the dew was still on the ground, our pants would be black. Once they dried, you could brush away the fly ash like dried oatmeal.

Every summer, one of my jobs was to clean the maple tree saplings growing in our gutters. The gutters would become so clogged with fly ash and grit that the whirlybirds would take root. When you blew your nose, your handkerchief looked like your sinuses were full of coal tar. The day after a snowfall, a black crust would cover the white.

When I was a freshman at Bowling Green State University, my roommate and I were walking to class a few days after a snowstorm when I remarked that the snow was remarkably white. He looked at me like I had purple horns growing out of my head. “It’s snow,” he said. “What other color would it be?”

“Back home, the day after it snows, it’s black,” I said.

He shook his head and said, “Where in God’s name are you from?”

It was at college that I learned that not everyone shared my belief that the Ohio Valley was a special place. People from other parts of Ohio looked with disdain at the valley with its smoke and mills.

I had a football coach in college who, when he was trying to chat up his players, would say, “How are things in Cleveland, Joe Smith,” or, “How are things in Columbus, Bill Jones.” Then, he’d look at me and say, “Yocum, you and those boys from down in that valley….” And he’d spew “valley” like he had a mouthful of soured milk.

(I missed the team bus and was late for a pre-game walk-through at Southern Illinois, and he came up to me and said, “Didn’t they teach you to tell time down in that valley, Yocum, or are you just stupid?” Here’s the rub. I knew that he knew I could tell time, so I had to fall on the sword and confess to my stupidity.)

Although I miss the valley, the truth is that I ran away at the first opportunity. My father arranged for me to get a tour of Weirton Steel between my junior and senior years in high school. In retrospect, I’m sure he did that so I could see what my life would look like if I didn’t get to college. That was the dichotomy of my youth.

Every good man I knew went to work with a tin lunchpail in one hand and a hard hat in the other, including the men in my family. We were strictly blue-collar—steel workers, coal miners, and railroaders. When my maternal grandfather finished the fifth grade, his father told him, “You can read, write and figure numbers. That’s all you need. Time to get to work.” He was ten when he went to work in the glass factory in my hometown of Brilliant, Ohio.

Perhaps I romanticize those days and reflect on them the way a guy in a bad marriage thinks about his high school sweetheart and wonders if his life would be different if he’d married her. I still miss the Brilliant of my youth, and I’m not sure I’ve ever felt more a part of a community. I knew my place in the world. I was Ron and Carroll’s son, the Wheeling Intelligencer paper boy, and a varsity letterman.

Sadly, things have changed dramatically in the Ohio Valley. The mills that once stretched along the banks of the Ohio River for miles have been shuttered, as have the other industries.

The once-thriving towns along the river are showing their age, the sad reality of losing their industrial base. Downtown Steubenville is attempting a revival, but it’s unlikely that it will ever equal the heyday of the steel era, when downtown had four five-and-dimes, The Hub Department Store, four movie theaters, and dozens of other thriving businesses.

Novelist Thomas Wolfe is credited with the often-heard phrase, “You can never go home again.” That’s true. The Ohio Valley of yesterday is gone forever. And for that reason, it’s important to me to keep it alive on the pages of my novels.

***