“You own everything that happened to you. Tell your stories. If people wanted you to write warmly about them, they should have behaved better.”

― Anne Lamott, BIRD BY BIRD

I first heard this quote while listening to Anne Lamott’s inspirational TED Talk. As a writer, her words made me feel empowered, even emboldened. Lamott was giving me carte blanche to write about every crappy ex-boyfriend, cruel boss, and self-centered friend that had done me wrong. Where to start? But I never followed through. Maybe I was too cowardly. More likely, I realized my jerk ex-boyfriends and mean bosses weren’t all that unique or interesting. And in this era of social media and online vitriol, writing about real people can be a risky venture.

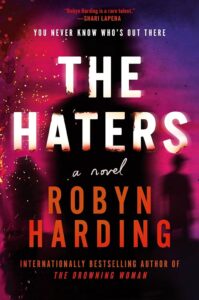

In my novel The Haters, a high school counselor turned author is accused of writing about her students’ private lives. She’s horrified by the accusation which threatens her writing career, her counseling job, and, eventually, her life. But there are many creators who admit that their characters are based on real people. How do they write about them while still respecting their privacy? And should they have to?

One of literature’s most famous villains, Hannibal Lecter, was based on a real person. Author Thomas Harris met an inmate while doing research at a Mexican prison. Dr. Alfredo Ballí Treviño was a charismatic surgeon convicted of murdering his lover in a crime of passion. (He was also suspected in the murder and dismemberment of several hitchhikers, crimes similar to Harris’s character Buffalo Bill in The Silence of the Lambs). Even Psycho‘s Norman Bates bears a resemblance to the Butcher of Plainfield who lived only a few miles from author Robert Bloch.

The Hulu series Under the Bridge (based on Rebecca Godfrey’s book of the same name) tells the story of teenager Rena Virk’s beating and murder at the hands of a group of kids in Victoria, BC. Author Godfrey spent years researching the crime, even building relationships with the accused killers. Because I live in Vancouver (a two-hour ferry ride from the crime scene) the show has sparked a lot of discussion in my social circles. My hair stylist wondered if the Virk family was getting any money from the show. At a dinner party, guests debated if the series was exploiting a tragedy for entertainment value.

I believe there can be value in exploring real life crimes through fiction. If handled delicately writers are able to pull back the curtain on these dramatic events, humanizing the victims, and sometimes, even the monsters. This allows a deeper understanding of human nature and society. It educates and creates empathy and compassion. But sometimes “based on a true story” can go wrong. Sometimes, it can turn into a legal and ethical nightmare.

The novel, Will and Testament, caused a literary scandal when it was published in its native Norway. Much-lauded author, Vigdis Hjorth, based the novel on abuse she suffered at the hands of her parents, a claim the rest of her family denies. The country became embroiled in a debate over “reality literature” (writing that draws on identifiable characters and events, usually without their consent). Hjorth’s sister Helga, a lawyer, wrote her own novel, titled Free Will, in an effort to set the record straight.

The Netflix series Baby Reindeer became a huge hit… and the subject of much controversy and debate. Comedian Richard Gadd recounts his real-life experiences with an obsessive and abusive stalker he calls Martha. While names were changed (including his own), he cast an actress who resembles his alleged stalker, shares her accent and provenance, and he used, verbatim, some of her tweets and e-mails. It wasn’t long before fans identified the real-life Martha as Fiona Harvey (a woman who, it now appears, has no criminal record but who did once have a writ filed against her for a stalking another man). Harvey received harassing messages, phone calls, and even death threats. She appeared on Piers Morgan Uncensored to deny stalking Gadd and is now suing Netflix for $170 million for defamation.

Did Gadd and Netflix have a duty of care to protect the woman who allegedly harassed Gadd relentlessly? By Ann Lamott’s credo, Gadd has the right to tell his own story, and victims should feel empowered to raise their voices. But should Gadd have more heavily fictionalized his experience? Should Netflix have done more due diligence?

Memoirists routinely write about their lovers, families, and friends, often in highly unflattering ways. One of my favorite memoirs is A Beautiful Terrible Thing. Author Jen Waite recounts meeting the man of her dreams, marrying him, and while pregnant with his child, realizing that he’s a heartless sociopath. Jen is a friend and I asked her about writing someone once so close to her, and so easily recognizable to those in her life.

“I was scared that as soon as my ex-husband heard about [my book] he would…sue? Threaten me? Contact my publisher?” Jen told me. “So, one night I wrote a Facebook post about the memoir and set the audience to “public.” The next morning, I checked my Facebook. At 2:00 A.M., my ex-husband had liked my post. We weren’t friends on Facebook, but I didn’t have him blocked either.”

“I took a moment to sit with what that like meant,” Jen continued. “I realized that his cheeky like signaled that he found pleasure (or amusement?) in the attention the memoir would bring, no matter how negative. Perhaps it fed his ego, or maybe he just liked that I had spent months of my life dissecting him on the page. Either way, he wasn’t going to come after me. He was going to enjoy this.”

“What I didn’t expect,” Jen said, voice resigned, “were the scathing reviews that came in from readers. All the trade reviews had been positive. I didn’t expect the hatred that some would feel for the memoir. I felt every bad review deeply and let them fester under my skin. It was so hurtful and so personal.”

So, tell you stories… At your own risk.

***