Chicago has produced more than a few successful African-American writers, in both the literary and sales sense, including Richard Wright, Gwendolyn Brooks, Lorraine Hansberry, Willard Motley and Sam Greenlee. Inspired greatly by Richard Wright, whose classic texts Native Son and Black Boy helped create a literary path for many Black boys with a pen and a headful of ideas, novelist Ronald L. Fair isn’t as well known as his textual contemporaries, but he was another wonderful writer who emerged from that hard city. Fighting every step of the way as he embarked on the revolutionary road of creating literature on his own terms, he had a bigger mission in mind than just fame and fortune.

“I doubted that I would ever make any money as a writer of this kind of fiction, but that didn’t matter because I would be telling it like it is,” Fair wrote in an essay published in the April, 1965 issue of Negro Digest. “No more polite lies. No more biting of the tongue or twisting of truths. Richard Wright’s death would mean something, because I would keep him in mind and swing away.”

According to “Bearing Witness in Black Chicago” by Maryemma Graham (1990), “Fair began writing in high school in order to provide an outlet for his own developing and inquiring mind. Like Red Top, a character in the novella ‘World of Nothing,’ writing was a mental and spiritual exercise. But the path that led to a literary career was interrupted by three years in the Navy and two years at a Chicago business college. Then Fair spent ten years as a court reporter for the city of Chicago.”

Fair’s 1963 debut was the slim Many Thousand Gone: An American Fable. A dark satire in more ways than one (it was reissued last year from the Library of America), the book depicts a fictional Mississippi town called Jacobs County that neglects to tell their local “colored folks” that slavery is over.

After a few of the slaves, most notably Jacobs County elders Granny Jacobs and Preacher Harris (the only Black person in town who could read) discover that there exists a free world beyond their plantations, they became fixated on getting their families to the Negro Promised Land they believe Chicago to be. When a copy of the Black-owned/Chicago based Ebony magazine is mailed to the town, word gets out that there was a place where they could live as nicely as white people and keep a few dollars in their pockets.

When Fair decided to satirize slavery it could have gone all wrong, but, as Negro World (owned by Ebony’s parent company Johnson Publications) observed in 1965: “It is a measure of Mr. Fair’s artistry that the pain and fury behind the laughter is always finely felt.” Yet, while the golden streets of Chicago and other northern wonderlands (Pittsburgh, Detroit, New York) served as the perfect strivers’ fantasy, the reality of those harsh, cold cities was quite different than expected: shabby tenements, and later housing projects, replaced the plantations and the laws of justice still weren’t balanced.

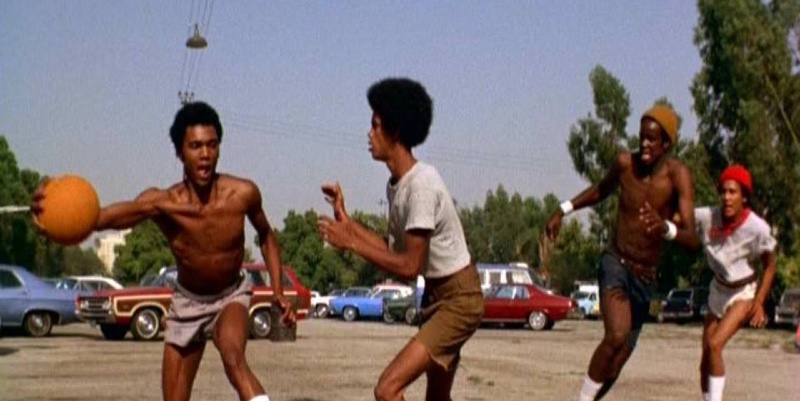

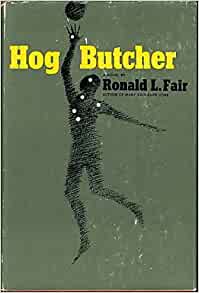

Fair, whose own parents made the sojourn from Mississippi, was born and raised in Chicago and knew very well the levels of race inequality that were prevalent in housing, schooling, banking, salaries paid and the policing of Black communities. These heavy subjects are tackled in Fair’s powerful and naturalistic second novel Hog Butcher (1966). This told the story of a college-bound Chi-Town high school basketball champion headed for college named Nathaniel Hamilton, whom everyone calls Cornbread.

A neighborhood hero, Cornbread is gunned down by a white policeman who mistook him for a thief as he ran home in the rain holding a bottle of orange soda. The policeman, half an interracial duo of blue boys, thought Cornbread was the burglar they had been pursuing minutes before, but his deadly mistake causes the community and “the system” to explode. A small riot breaks out minutes after Cornbread is slain and the mayor’s sends in a task force of, “twelve officers, all over six feet, cruising slowly down the block on motorcycles. They were so big the motorcycles looked like children’s toys under them,” to occupy the neighborhood like a military force.”

With the only witness to their senseless crime being a ten-year old kid, Wilford Robinson, who along with his buddy Earl, idolized every cool Cornbread made on the battlegrounds of the basketball courts, the goal of everyone including civic leaders, the welfare agency and violent cops, one who beats-up Wilford’s mother, is to make the boy be quiet. As the state builds their web of lies, the truth becomes the scariest enemy.

Negro Digest editor Hoyt W. Fuller wrote in the October, 1966 issue of that publication, “Hog Butcher is…a sharp portrayal of a diseased city. That the picture might fit any American city is merely coincidental.” Author Richard Guzman, editor of Black Writing from Chicago: In the World, Not of It?, wrote a 2015 essay on Fair and Hog Butcher, “Though some have commented on the novel’s humor and, in particular, on the energy and courage of the two adolescent protagonists through whom some of the action is seen, the novel is a sobering exploration of social class … and, of course, police violence.”

In The Contemporary African American Novel: Its Folk Roots and Modern Literary Branches (2005) author Bernard W. Bell wrote that Fair borrowed the term “hog butcher” from Carl Sandburg’s 1914 poem “Chicago” (‘Hog Butcher for the World, Tool Maker, Stacker of Wheat, Player with Railroads and the Nation’s Freight Handler; Stormy, husky, brawling, City of the Big Shoulders…’), but also believed that “the white Chicago system is the hog butcher that cuts out the souls of blacks.”

Maryemma Graham notes, “Hog Butcher, considered by most critics to be (Fair’s) best, drew heavily upon his intimate knowledge of Chicago’s legal system. Fair sets up the oppositional forces in Hog Butcher on several levels… Fair is quite detailed in his descriptions about how the police department and the court systems work with regard to black people and the black community, obviously drawing upon his years of experience as a courtroom reporter. This necessarily leads to a focus on the social dynamics of the black urban experience, a fact which invited some very negative reviews from Fair’s critics.”

“Hog Butcher was different from any novel I had ever read,” novelist Cecil Brown wrote in a 2020 essay. Brown, who considered Fair one of his literary heroes, met him in 1966. “His prose was exciting and infectious; you could not begin reading one sentence without reading the next sentence. But the most important thing was it was about police brutality. The story was set right in Chicago where we were having riots.” When Hog Butcher was reissued in 2014 from Northwestern University Press, Brown wrote the forward,

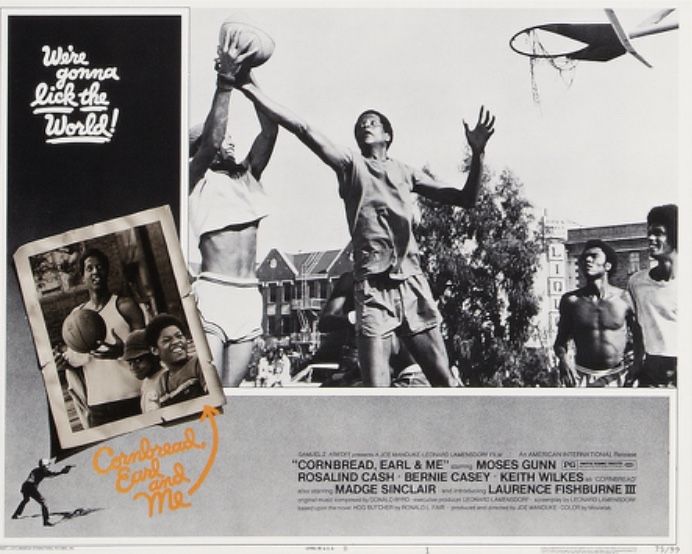

In 1975, during the height of the Blaxploitation movement that was going down in American movies, Hog Butcher was adapted by screenwriter Leonard Lamensdorf and director Joe Mandrake. Released under the title Cornbread, Earl and Me, the picture was an American International Picture release that starred thirteen-year-old Laurence Fishburne in his film debut as Wilford. There was also NBA star Keith Wilkes as Cornbread, Rosalind Cash as Wilford’s mother and Bernie Casey playing the other policeman. Soul-jazz unit The Blackbyrds did the soundtrack. Though not as brilliant as the funky scores composed by Isaac Hayes or Curtis Mayfield, leader Donald Byrd created a serviceable soundtrack.

While filming the adaption, considered a classic in some quarters, told the story from Wilford’s point of view, Fair used the third-person omniscient that showed readers how Cornbread’s murder affected each side from the Black cop and the frightened grocery store owner to the uncaring Deputy Coroner and the knight in shining armor lawyer Benjamin Blackwell, who was working for Cornbread’s family.

In Cecil Brown’s forward to the 2014 edition, he wrote, “Mr. Fair presented a new style of writing in Hog Butcher. The story is told not in a traditional narrative mode, but in an impressionistic style that relies heavily on interior monologue. The style enables Fair to move into and out of the minds of different characters and back and forth between past and present. Along with Richard Wright’s first novel, Lawd Today! (published posthumously in 1963), Hog Butcher can be seen as a milestone in the use of interior monologue to portray the consciousness of African American characters.”

Although Fair never claimed that Hog Butcher was based on a specific case, almost sixty years after its initial publication the novel serves as a reminder that American police brutality in the Black community wasn’t something that began in the age of cell phone cameras, police dashcam footage and surveillance monitors. Four years before the film version was released, Fair was encouraged by writer Chester Himes to flee the racism of Chicago in 1971; he lived in various European countries before finally settling in Finland in 1972.

Since Hog Butcher was reissued in 2014, more writers and critics have embraced the book, including a chapter I wrote for Sticking It to the Man: Revolution and Counterculture in Pulp and Popular Fiction, 1950 to 1980 and an essay by writer Kathleen Rooney, who stated in 2022, “I would like to nominate Fair’s novel to appear alongside To Kill a Mockingbird on syllabi everywhere because instead of exceptionalism and white saviors, Fair’s story depicts—with a cast of lovable, hateable, believable characters from the young man who gets murdered to the cops who murder him—how power’s highest aim is always to preserve itself and how collective action is the best hope anyone can have against systemic injustice.”

Though his work is important, Fair didn’t think America appreciated Black writers. “Being a Black writer was a dead end,” Fair told Cecil Brown in 2010. Eight years later, in February, 2018, Fair died from a a cerebral hemorrhage. He was 86. According to his widow Hannele, though he stopped publishing, Ronald L. Fair never stopped writing. “I have many of his unpublished manuscripts with me that deserve to be published,” she wrote Cecil Brown in 2018. Hopefully one day those works will be shared with the world.