N.B. (1): For our purposes here today I will use “crime fiction” as a catch-all term for thrillers, mysteries, and variations thereof.

N.B. (2): References below to assorted crime fiction tropes are made with great fondness and appreciation.

N.B. (3): If you or a person of your acquaintance worked in the costume department for the television adaptation of Sara Shepard’s Pretty Little Liars, please be in touch with me immediately regarding the hats in season one.

As a writer with a new book coming out, there are a few things I have freshly added to my to-do list. Stockpile photos of myself holding my book while dressed in nice clothes so nobody will realize I usually just alternate between two Old Navy crewnecks. Redownload Instagram to my phone, but make sure to hide it in a folder to keep from scrolling all day. Sketch out some responses to questions I am likely to get asked at book events so that I don’t come across like an airhead.

That last one is especially important, because I’ve learned that questions like “What inspired you?” demand a certain kind of answer. People want me to tell them about the photograph I saw and saved to my phone (a selection from Phantom: Stage One by Neil Krug) or the cult-classic movie my mother talked about all the time growing up (Peter Weir’s Picnic at Hanging Rock). Generally speaking, they seem distinctly less impressed when I say, “It was a lot of things all smashed together into clay and then fired in the kiln of this one month where I was rewatching the ABC Family show Pretty Little Liars and kept getting mad because they wouldn’t let the titular liars just straight up murder people.”

Frustrated as I was during my rewatch, I understand why it had to be that way. Advertisers, the fact that “family” is in the name of the network, a young audience, etc. But I think it’s also a function of the genre that Pretty Little Liars occupies. During a stint as an editorial assistant at a crime fiction imprint, my then-boss described the genre as a way to uphold society, to reinforce what we traditionally understand to be moral and good. We watch as our social mores are broken, then watch as the world is put back in order. Let the grizzled detective with an estranged daughter and a secret personal connection to the case reassure you that what lurks in the woods cannot reach you here at the village fire.

In that context—crime fiction as fable, as a modern morality play—there’s a specific story beat that fascinates me. You will probably recognize it just as you did our grizzled detective. Picture our main character waking up after a night out. She can’t remember where she was, but there’s blood under her fingernails, which isn’t a good sign. She waves it off, tells a breezy lie to her coworkers, only to learn that her boyfriend was murdered last night. My God, she thinks, looking at herself in the bathroom mirror. Was that me? Did I do it?

Well, no. Or rather, almost never. And if she did, it was probably self-defense, or because her boyfriend was a bad person and he deserved it.

The beat functions in the same way crime fiction at large does, puncturing our sense of safety and then sealing that puncture up. But where crime fiction tells us that our world is ultimately good, this smaller story beat tells us that we ourselves are good. Consciously or otherwise, readers are inclined to connect with, relate to, and even identify with a story’s main character. When a protagonist doubts her inherent goodness, that doubt echoes off the page and into the reader; when she is comforted, so are we. Don’t worry, Pretty Little Liars says as one of its leads realizes that instead of killing her friend, she only waved a field hockey stick menacingly in said friend’s direction. Spencer Hastings is a good person, and you are, too.

These days, that reassurance feels flimsy. Recent years (and, one might well argue, a great many of the years preceding them) seem defined by watching the proverbial line in the sand be crossed over and over again. I have very little shock in me anymore. The question of “who would do such a thing?” feels asked and answered.

As somebody who writes whodunits, this is a particular sort of troublesome. In 2022, as I tried to brainstorm for a new book, it was a knot I couldn’t quite untangle to my satisfaction. It wasn’t until I sat there rewatching Spencer and her field hockey stick that the knot finally gave.

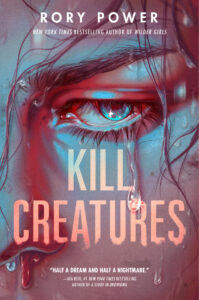

In my young adult novel Kill Creatures, the main character Nan opens with a clear confession. A year ago, she says, she murdered her three best friends. She misses them, yes, but she wouldn’t change it, and she isn’t sorry. That question, asked and answered. Who would do such a thing? Nan would. Nan did.

Starting from that fact completely broke the book open for me. With that foundation of Nan’s character in place, I could reframe the story, free readers from the responsibility of serving as Nan’s judge and jury, and focus on the questions that interested me most: How do we carry on through life without the shield of our assumed goodness? What comes after guilt? And, as ever, where do we go from here?

The thing is, it’s a short book; I didn’t exactly have time to find all the answers. I could only find Nan’s. Maybe, if you read Kill Creatures, you’ll find yours.

***