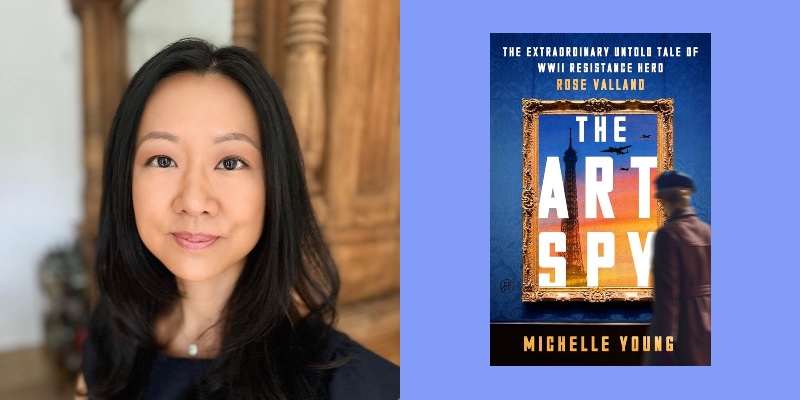

If you’ve read books about spies and resistance fighters in World War II-era France, there’s a decent chance you’ve come across the name Rose Valland: the woman who tracked Nazi looting from the inside. But most of those accounts offer scant detail about her life or wartime activities, and others leave her out altogether. Now, with The Art Spy: The Extraordinary Untold Tale of WWII Resistance Hero Rose Valland, Michelle Young has revealed the extent of her commitment and bravery.

After laboring in various underpaid curatorial jobs as a result of being a woman, Rose was well-placed to observe Nazi interlopers at the Jeu de Paume Museum in Paris throughout the war. There, she meticulously documented who was looting priceless art, from Jewish families and also from the state, and collected as much information as she could about where pieces were traveling to. She risked her life—and the life of her partner, Joyce Heer—by doing this work. If the Nazis had found out about her activities, or indeed about her sexual orientation, she would have been killed (at one point, as Young writes, there was a plot to kill her that came close to being carried out).

Despite her heroics, and the years she spent working to recover stolen art after the war, Valland remained an obscure figure for decades in France. In part, as Young explained to me, this was due to Rose’s own memoir, which left out many personal details in an attempt to clarify the historical record—and to be taken seriously. “So many times, she would cut out things that would actually be interesting from a narrative nonfiction perspective,” Young says, “because she was really trying to prove the case against Nazi looting.”

Happily for us, Young had access to this earlier draft, and used these cut details in The Art Spy, a riveting narrative that fuses Rose’s story with the wider story of Nazi looting and the story of the Rosenbergs, a Jewish family whose art gallery, home, and family art collection were ransacked during the war. Though Young’s narrative stays firmly in the past, the totalitarian power structure she describes, and the danger that structure poses to art and artists, are eerily resonant in today’s climate.

Though this is the first work of narrative nonfiction Young has authored, she’s hardly a stranger to history or research: the founder of Untapped New York, she’s also an adjunct professor of architecture at Columbia University and teaches at CUNY’s Newmark School of Journalism. “I want to make new discoveries, and make information exciting to people,” she says, a goal that is consistent across her professional enterprises. But after the experience of diving into Valland’s life, she’s excited to continue pursuing the “detective work” of narrative nonfiction. “My whole life, I’ve been extremely dogged in whatever I’ve done, and I realized that writing narrative nonfiction is the perfect outlet for that, because you get years to do it and it pays off in terms of exhausting any possible lane of inquiry.” Her doggedness has resulted in a thrilling and valuable new addition to the long list of World War II spy tales, this one highlighting a queer woman who is finally getting her due.

Morgan Leigh Davies: How did you find Rose Valland, and what made you want to tell the story?

Michelle Young: I was reading practically exclusively books about female spies. Someone [said to] me the other day, I assume that’s a hyperbole. I was like, It’s not a hyperbole. I probably spent at least half a decade doing that. When I did come across Rose Valland, it was in a more academic book called Göring’s Man in Paris by Jonathan Petropoulos, about art looting and Göring’s art dealer in Paris, who was in the Jeu de Paume Museum where Rose Valland worked. Every chapter, this woman named Rose Valland would appear and I would think, How come I don’t know about this spy? I’ve read all the nonfiction spy books. I’ve read the compilation spy books about female spies, and she didn’t appear in them. How does someone become totally forgotten? Am I the person that could write a book about her to bring her to light?

I started to explore it and I showed up in her hometown. For me, going into a place is extremely important. I have an architecture background and urban planning background, so I just like to get the feel. The first thing I found out when I got there was that there was a plaque, a Rose Valland Place, but it was the parking lot of the post office. That really struck me. Even in the town she’s from, this is where they’ve placed her. It was such a disconnect with how I read her life story. One of the most medaled women in World War II, did amazing, daring work in World War II—how does that happen?

MLD: I was thinking reading this, and I feel like I think this so often reading books about these women who were spying in Europe at this period, that so much of the popular idea of what a spy is, is something like James Bond, which of course we know is nonsense. But especially in this case, her work is so quiet. How do you construct a narrative around a figure like that?

MY: One of the things that I wanted to do is to tell this broader story of art looting and laying it out. In layman’s terms, there were just decrees and decrees and decrees [allowing looting]. That was one way to position the work she’s doing vis-à-vis what’s happening with all these Nazis, these very evil, straight out of central casting characters. That’s why I also added the secondary storyline of Alexander Rosenberg and his family. That was to tell the story of looting from a personal perspective, from a family that went through this, but also to tell the wider story of the war because Alexander is fighting. Only having her in the museum, writing down documents, impressive as that is, it’s not enough for a book like this. So there’s a lot happening at any given time.

I also read her notes really carefully, and realized, for example, she wouldn’t say, I went out and I tailed this guy home and saw him put art into a truck, right? But her notes were like: and in the evening, this guy put carpets and paintings into his truck and this is his address and his apartment is on the second floor on the right side. She didn’t have someone report that to her. She obviously was there. It was reading the documents and trying to understand what went into any given dry report about something and positioning her in that.

MLD: It also made me think about different kinds of resistance, especially in our current moment. It’s easy to romanticize people who shoot people or blow things up. But that just wasn’t possible in this scenario. I was very moved by the fact she’s doing all of this on the future hope that this will be worth something.

MY: I got that directly from what she wrote. It was almost this optimism that the Germans would lose the war, because she says, I’m doing it for a future war tribunal, basically. She was very disturbed by the principle of art looting. So she’s being driven by this very deep-seated and greater belief that good will prevail and that she has a role to play in that, which must take an incredible fortitude of character. In a chapter that had been cut from her memoir was the episode of her escaping from Paris as Germans are coming in. In that chapter, there’s a moment where she sees a woman and her two dead children in a baby carriage on the road to the Loire Valley. She says that that’s the moment that she decides she’s going to fight back no matter what, in whatever way she can. To discover those lines, I was like, oh my god, now we know part of the origin of her motivation. It’s seeing tragedy before her.

MLD: A lot of the emotional reaction I had to the book was to these horrible, horrible people coming in and just taking stuff. They created rules for what they could take, and then broke all the rules.

MY: There are so many papers about all of the decrees that were sent. They were using euphemistic language to justify why they were stealing things in the first place, and then creating a set of rules that would enable them to steal. It was just one thing after another. I think the most disturbing thing was how they just slowly stripped away the rights of the Jews partially to steal their stuff. Yes, later they just took everything from them, including their lives. [But] it begins so slowly.

First, you’ve got to declare anything over 100,000 francs. Next, you have to come and sign in at the local prefecture every day, or whatever. You can really sense how in any given scenario, one might not realize where it’s going. So some people dutifully followed the rules and then they used those documents later to find them and deport them to extermination camps. I felt like I had a responsibility to show this larger line in this picture, that it’s not just a bunch of people who like art stealing art for the sake of stealing art. It’s part of something much more sinister, and they’re stealing art also because it’s greed and power. I feel like it was more power even than greed. It became almost disconnected to the art itself.

MLD: There’s also the progression that you show from where initially they’re taking paintings, and then as the war goes on, they’re like, let me take all of your rugs and curtains.

MY: It was everything, just emptied. It’s like the minute people were deported, they went into their apartments and they emptied the whole thing down to tea sets and silverware. That last train that Rose is trying to stop from Paris, most of it is furniture and personal items. People know that train from the 1,000 paintings she’s trying to save, but that’s like five train cars. There’s like 48 others that are of this stuff that represent the lives of these people.

MLD: I wanted to ask about the destruction of the paintings. This is something that Rose writes about and that was controversial in her memoir, and was not something that I had had read about elsewhere.

MY: So in July, 1943, the Nazis have amassed a lot of modern art by Picasso, Dalí, Léger, the most famous people we know today. And they don’t know what to do with it because Hitler hates this stuff. So they can’t move it to Germany. It’s piling up in at the Jeu de Paume, and Rose is really worried about it; she’s been worried about it for years. What are they gonna do with this stuff?

She starts to see them separate the modern paintings into several categories with a letter and she doesn’t really know what they mean. Then one day they start to destroy the paintings. They start by knifing them and kicking them, removing them from their frames, tearing up the canvases. And then they bring the tatters and the paintings to the Jeu de Paume courtyard, where they instruct the guards to set them on fire.

I knew she had reported this event and I knew that there was doubt about it. I had seen several books call it into question. I needed more evidence either way. But I knew if I was telling this from Rose’s perspective, I would need to address it somehow. If I didn’t find anything, I’d have to address the fact that there’s a question about the account or decide not to talk about this event. I knew if I wanted to tell it as truth, I would need some kind of smoking gun, something that shows that it happened. So one day I was going through the documents I had photographed and in the back were these handwritten testimonials that were notarized. I was like, these are the guards in the museum. I know these names and I think they’re talking about this event. My husband woke up and I was like, Is this what I think it is?! He’s like, It is! I was so excited. To me, this is the one huge discovery of my book.

Obviously not everyone knows that this account was called into question, but I really wanted to prove it one way or another. Later I found a contemporary newspaper report in a newspaper called Résistance, which talks about it. They published it a couple of months later. I felt with the four notarized testimonies, and there’s another letter from the head of security at the Louvre, which actually he wrote the day it happened, and then the newspaper report—this is definitely enough.

MLD: It wasn’t unbelievable to me that the Nazis would burn these paintings.

MY: They had been doing it already. They had been doing it in Germany, both paintings and books. One of the first things I did was track down, where did this doubt come from? And it was the Nazis who were in the museum who had given the orders. They came out and did an interview with Der Spiegel, the German paper, after Rose’s book comes out to say it never happened, and if it did, Rose was implicated because her handwriting is in the inventory. How can we trust that? How can we put into the record that there’s doubt based on partisan defense attempts?

MLD: You write about her being almost forgotten by the time she’s dead, and obviously this book is a huge revival of that legacy. Could speak about what happens to her after the war?

MY: After the war, she’s pretty celebrated. They gave her lots of medals. Nearly two decades after the war, she writes this book, which then partially gets turned into a Burt Lancaster movie called The Train. But she stayed a long time in Germany after the war, almost 10 years doing restitution work. By the time she gets back, she’s kind of missed out on some of the job opportunities she could have had with all her post-war fame. And then the world is in the Cold War and they don’t want to talk about Nazis, they don’t want to talk about Nazi art. And there are a lot of French families who are complicit during the war and they’re back in power. So she becomes really an inconvenient presence.

She moved around the French museums and [was] put into far away offices. By the time she dies, almost nobody attends her funeral. I mentioned in the book this one letter that the head of culture at the time, who writes two decades later that he was appalled to discover that he had not been notified that she had died. So she dies, basically, in obscurity.

And then I think in 1999, her hometown puts together a conference. At this point, some of the resistance people are still alive. They come and they talk about her and her work and the Association for Rose Valland is created. This begins this more than 20-year journey to highlight her. There have been some exhibitions in France, some books related to those exhibitions published. Finally, I think it was last year or a year and a half ago, they renamed the plaza next to the Jeu de Paume Museum for her and they did a big ceremony. There had been a plaque also against the wall, but it was on the side.

For some reason, she’s always conveniently forgotten. One of the compilation books I read was a 2019 book from France about female resistance people, and she wasn’t in it. I think it’s a combination of what happened post-war to her, but also going back to this idea of cloak-and-dagger. People don’t see her, especially in France, as being in the resistance. One of the things I got, even from my in-laws: Was she really in the resistance? And I’m like, she has a Medal of Resistance, what more proof do you need? You can see in her memoir, she’s constantly trying to prove herself. There is a moment where she indicates that she’s doing this because people are questioning her role. She fought this battle in her lifetime and I feel like that battle continues.

MLD: I’m curious sort of what you feel like you learned about sort of fascism and resistance by immersing yourself in this woman’s life.

MY: These thoughts about the present day were very present in my mind as I was writing it, and not because I was searching for those links. It’s actually just from reading the verbiage of the Nazi documents and how they talked about art and architecture. It was impossible to ignore it. And the story of the Rosenbergs and the Jewish population in France really struck me too, because it became about: Did you escape early enough? That question was terrifying to me. At what point do you see what’s happening around you and realize that you are at risk? The people who waited too long died. As we get closer to publication date, the echoes are even stronger in terms of the attack on the arts that’s happening now. I’m not the kind of writer that even really knows how to write in a very moralizing tone, but I wanted to present it and then hope that people realize that maybe some of the things happening [in the book] might affect them at some point.

MLD: These people coming in and treating France as like their personal playground really reminded me of people in the government right now.

MY: Kurt von Behr, the guy in the museum with the glass eye, is purely there to take advantage of the situation, and he doesn’t hide it. He’s just like, oh, great. The best wines from like the Rothschilds? I’m going to take it and I’m going to wine and dine. He doesn’t pretend to be interested in a highfalutin way about art, which some of the higher-level Nazis tried to—like Göring tries to indicate that it’s about the art.

I also thought about a lot about the collaborators because, you know, in any given situation, people make their own decisions about if they want to collude or if they even think it’s colluding or it’s dangerous. I didn’t try to be too judgmental about that, because one never knows in what scenario one might become a collaborator. But I did think about their later legacy. Some of these people picked the wrong side.