There was a time, a time before touch screens and artificial intelligence, a time before all things considered became one thing considered, a time before passion became an ordinary word. It was during this time that I wore a leather jacket and studied with Professor Jules Winfield at UCLA. Winfield was teaching a class at Kinsey Hall he called “Miracles, Epiphanies and Other Human Phenomena.”

Professor Winfield was something of a legend in Westwood. According to The Ray Manzarek & Jim Morrison Preservation Project, Manzarek and Morrison both studied film at UCLA in the 1960s and Professor Winfield was an early influence on Jim Morrison.

Morrison and Winfield worked on an experimental film project they called “Breakthrough.”

No one alive has ever seen any footage from the Morrison-Winfield project. It is believed to have burned in a bungalow fire near Venice Beach. What is known is that Jim Morrison and Ray Manzarek eventually abandoned UCLA and went on to form The Doors. It is also known that the first song on the first side of the first Doors album is called “Break on Through (to the Other Side)” and that it opens with a declaration from Morrison in a voice unlike any heard before:

You know the day destroys the night

Night divides the Day

Tried to Run

Tried to Hide

Break on Through to the Other Side.

Years later, when I caught up with Professor Winfield, he was still at UCLA, teaching his seminar on miracles, epiphanies and other human phenomena. Winfield, with his bow ties and spectacles, looked like Satch Sanders, but when he lectured his eyes had the intense glow of Bill Russell swatting away a rival’s shot at the rim.

Winfield described the experience of “breaking through” as the experience of a “singular moment of clarity.” He called it the moment “when water turns into wine,” when you can hear “the cosmic tumblers click into place.”

My notes from his class also contain this pearl:

“There are things you know about, and things you don’t, the known and the unknown, and in between are the doors.”

Professor Winfield’s class didn’t end with an exam. He assigned each of the students an “independent study.” He directed us to find a “breakthrough” and describe it.

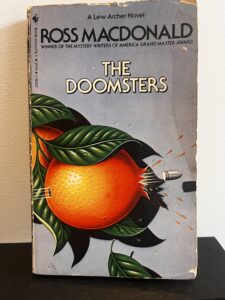

For my independent study I jumped at the chance to write about The Doomsters, Ross Macdonald’s 1958 crime novel, the seventh novel in Macdonald’s eighteen novel Lew Archer series. I had been obsessed with The Doomsters ever since my Uncle Paul had introduced me to the Archer novels. In those days, Paul lived near the elbow of Cape Cod Bay and I worked summers at Thompson’s Clam Bar on Wychmere Harbor. Paul let me sleep in his basement office. We watched Red Sox games, drank beer and read mysteries. Paul had a complete set of the Lew Archer novels and a set of six Philip Marlowe novels – from The Big Sleep to The Long Goodbye.

I read every one of those novels – in order of publication.

In between beer and baseball games, I discovered that The Doomsters was Macdonald’s breakthrough – the novel where Macdonald cracked the hard shell of the American hard-boiled crime novel created by Hammet and Chandler and found his own, and Archer’s own, unique voice.

I trace that voice to the opening lines of The Doomsters.

Open any copy of The Doomsters and you can hear it too.

My current copy, worn at the edges and water damaged from the marine layer, is the 2007 Vintage Black Lizard edition. But you can open any copy to page one, paragraph one, and you will encounter private detective, ex-cop, Lew Archer waking up from the night sweats:

“I was dreaming about a hairless ape who lived in a cage by himself. His trouble was that people were always trying to get in. It kept the ape in a state of nervous tension. I came out of sleep sweating, aware that somebody was at the door. Not the front door, but the side door, that opened into the garage. Crossing the cold linoleum in my bare feet, I saw first dawn at the window over the sink. Whoever it was on the other side of the door was tapping now, quietly and persistently.”

I don’t know about you, but I know I would hesitate to unlock that door and discover what’s on “the other side.” That locked door is the dividing line – the safety – between the known and the unknown.

But Lew Archer does not hesitate. He says simply: “I turned on the outside light, unlocked the door, and opened it.”

Archer opens the door to find Carl Hallman on the other side. Hallman, the “desperate-eyed junkie scion of an obscenely wealthy political dynasty,” – according to the back cover of my Vintage paperback.

Hallman has escaped – gone “over the wall” as Archer puts it – from the State Hospital for the mentally ill. He is still wearing his hospital-issued dungarees and has dirt mixed in with sweat on his shirt. Hallman tells Archer that his mother died in a suspicious drowning several years earlier, and, more recently, his father, a retired Senator, has also died under suspicious circumstances.

Archer, the ex-cop, thinks that one suspicious death may be considered an aberration.

But not two.

Carl tells Archer that his father, Senator Hallmann, was a hard, man who made his fortune from the profits on orange groves stolen from Japanese farmers. The Japanese farmers were forcibly removed from their farms and imprisoned during World War Two.

Senator Hallman swooped in and took the farms.

Carl Hallman thought that maybe this was his family’s “original sin” – the uncharged crime they were paying for now.

Hallman tells Archer he has been “locked up” at the mental hospital by his older brother to prevent him from learning, and exposing, the family’s dark secrets, and he has run away to hire Archer to investigate. Another “patient” at the Hospital – who Hallman won’t identify – told him that Archer was a man he could trust.

Hallman thinks he may be responsible for the deaths of both his parents.

But he is not sure. He desperately needs to know if he is ever going to regain his faculties.

So here is Archer, standing in his kitchen at dawn – a “hairless ape living in a cage by himself” – face to face with a desperate man he does not know but who needs his help.

He should kick Hallman out and go back to sleep.

Surely, that is what a hard-boiled hero should do.

But not Archer.

In that moment, Archer experiences an epiphany – he decides that this moment is a turning point: “one of those times when you have to decide between your own convenience and the unknown quantity of another man’s trouble.”

Archer chooses the “unknown quantity of another man’s trouble.”

Even if it means, even if it ensures, his own inconvenience.

This moment, in the first chapter of the seventh novel of the Lew Archer series, is the line of demarcation for both Lew Archer and Ross Macdonald.

After six well written, but not quite original, Lew Archer novels, Ross Macdonald was searching for something original. With The Doomsters, he broke away from the influence of Raymond Chandler, the writer who cast a giant shadow over Macdonald and American crime fiction.

That over-arching influence – the voice of hard-boiled noir that was ringing in Ross Macdonald’s ears was the voice of Raymond Chandler’s Phillip Marlowe. A voice that can be heard at its loudest in this epic passage near the end of The Long Goodbye:

“When I got home, I mixed a stiff one and stood by the open window in the living room and sipped it and listened to the groundswell of traffic on Laurel Canyon Boulevard and looked at the glare of the big angry city hanging over the shoulder of the hills through which the boulevard had been cut. Far off the banshee wail of police or fire sirens rose and fell, never for very long completely silent. Twenty four hours a day somebody is running, somebody else is trying to catch him. Out there in the night of a thousand crimes, people were dying, being maimed, cut by flying glass, crushed against steering wheels or under heavy tires. People were being beaten, robbed, strangled, raped, and murdered. People were hungry, sick; bored, desperate with loneliness or remorse or fear, angry, cruel, feverish, shaken by sobs. A city no worse than others, a city rich and vigorous and full of pride, a city lost and beaten and full of emptiness. It all depends on where you sit and what your own private score is. I didn’t have one. I didn’t care.”

Marlowe looked over the lost souls and the mean streets of Los Angeles and saw that he had every reason not to care.

The power and the pull of his voice are undeniable.

For Ross Macdonald, the influence Chandler exerted was almost too much for him to overcome.

Enough to send him to a shrink.

Enough to make him want to quit writing.

Until The Doomsters.

With The Doomsters, Macdonald broke free.

He found his own unique voice and transformed Lew Archer into a new kind of hard-boiled hero, one who sees the same broken world, broken streets, and broken people as Marlowe but who chooses – who “decides” – to care.

Whatever the inconvenience.

For the remainder of the Archer series; from The Zebra Striped Hearse to Black Money; from The Underground Man to Sleeping Beauty; just to name four of my favorites, Lew Archer is a hard-boiled detective who cares.

A detective just as concerned about the people he is investigating as he is about solving crimes they commit.

Near the end of The Doomsters, Lew Archer finally tracks down the source of Carl Hallman’s “troubles,” the “killer on the road,” and Archer discovers – in another moment of clarity – that the hunter can have compassion for the hunted.

Archer’s discovery comes in a beautiful, doom-defying passage – a passage that I think it is just as relevant today as it ever was:

“I was an ex-cop, and the words came hard. I had to say them though, if I didn’t want to be stuck for the rest of my life with the old black and white picture, the idea that there just good people and bad people, and everything would be hunky-dory if the good people locked up the bad ones or wiped them out with small personalized nuclear weapons.

It was a very comforting idea, and bracing for the ego. For years I had been using it to justify my own activities, fighting fire with fire and violence with violence, running on fool’s errands while the people died: a slightly earth-bound Tarzan in a slightly paranoid jungle. Landscape with figure of hairless ape.

It was time I traded in that picture on one that included a few of the finer shades.”

Reading this passage today, I think that Lew Archer is something of a role model for our turbulent times.

Maybe it is time for us to find the courage to open the door between the safety of the known and the challenge of the unknown. Time to choose between compassion and convenience. Time to trade in the old black and white pictures; time to dispense with the idea that there are just good people and bad people; time to accept ideas with a few finer shades.

I would like to believe that.

After I turned in my independent study to Professor Winfield, we went our separate ways.

But we stayed in touch.

Years later, Professor Winfield sent me a package.

Inside the package was a paperback copy of The Doomsters and a note directing me to the copyright page of the book.

It was a Bantam Book, with the black rooster in the upper left corner, just above the $2.95 price tag. This edition featured James Marsh’s beautiful cover art: a juicy orange hanging from a green tree with a bullet slicing neatly through the fruit.

I turned to the copyright page, located on the verso page following the title page.

The small print laid out the printing history of The Doomsters.

According to the copyright page, The Doomsters had been “serialized” in Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine from October to December 1958.

Serialized under the title “Breakthrough.”

I could hear the cosmic tumblers clicking into place.