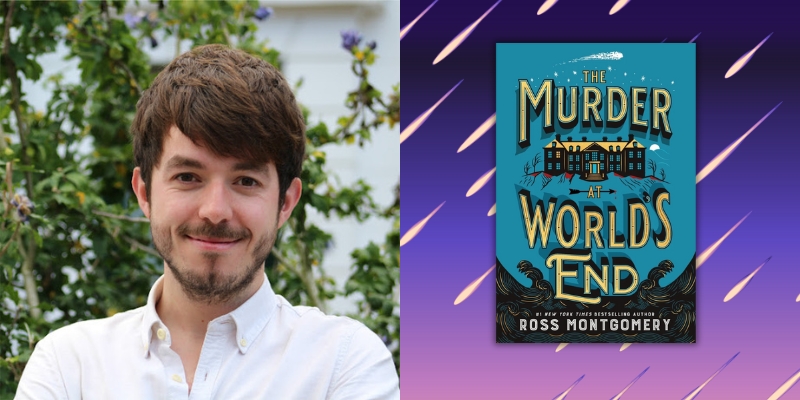

The new novel The Murder at World’s End is a locked room mystery set at an English manor house during the Halley’s Comet Panic of 1910. The Viscount believes the passage of the comet will poison the planet and after preparing for this, seals every guest and staff member in their rooms until the next day. Author Ross Montgomery did not invent this panic or the idea that Halley’s Comet might kill everyone on Earth, as we discuss. The precisely-crafted, laugh-out-loud narrative is all Montgomery, though.

The morning after the comet passes and the world has not ended, the Viscount is found dead in his study where he spent the night alone. The local police are useless and so the murder is investigated by his aunt, Miss Decima Stockingham—a woman so fierce she would make Maggie Smith’s dowager countess quake—and Stephen Pike, the house’s new under butler, who was just released from prison.

The Nero Wolfe-Archie Goodwin pair are deeply entertaining to read as she sends Pike to gather clues, break into rooms, and question people as they try to make sense of what happened and why. It’s a book that wears its influences on its sleeve, but when it’s so funny and well-crafted, it’s hard to mind.

I spoke recently with Montgomery about the Halley’s Comet Panic, Golden Age mysteries, researching profanity, and finding the Edwardian period to be not just fascinating, but a lot like today.

*

Alex Dueben: You’ve been writing kids books for years. What came first, the idea for this book or just wanting to write a book for adults?

Ross Montgomery: I’ve been doing children’s books in the U.K. for about fifteen years. I’ve never been short of ideas. Usually I’ve got too many. That is often a very bad thing. I’ve tended in the past to pile too many ideas into stories.

There were a few things that I was desperate to write about that I just knew I can’t make this a kid’s book. The very first seed of this particular book was learning about the 1910 Halley’s Comic Panic, which is the sort of setting of this particular murder mystery. I wanted to write about it, but where does a character fit into that? So I shelved it.

I realized that I did want to write for adults. It came around about the same time as lockdown, when I kind of rediscovered murder mysteries, which I think quite a few people did. For me, it started with TV series like Midsomer Murders. From there, going back into Agatha Christie. I realized that that was how I could combine the two ideas. I can use the comet panic as a setting, and I can turn it into a locked room murder mystery. I ended up building the story around that.

I knew that it was going to be a manor house murder mystery. It made sense in my head to do it as like an upstairs, downstairs, staff and gentry pairing. I like detective stories where you’ve got a central pair squabbling with each other.

I tried to work out like various permutations of how that could happen and eventually settled on this image in my head of Queen Victoria being pushed in a wicker bath chair by Greg from Succession. An elderly, posh relative, and this under butler. That’s how the detective pairing of Stockingham and Pike came about.

AD: Talk a little about the Halley’s Comet Panic, because I had never heard of this.

RM: That’s the thing. It’s one of those blips in history that only ever gets mentioned in blogs about weird bits in history. There was a resurgence of interest the last time the comet went past, which was 1986. It’s due back again in 2061, so we’ll probably hear a lot about it then.

Basically, Halley’s Comet was scheduled to go past in 1910 and if you think about what had happened since 1836, there had been so many like advances in technology and science. It had never been photographed before. People got really excited. Scientists wanted to study it in all these different ways that they could and so they used a spectroscope to analyze what was in the comet’s tail.

They found that it contained all these things, including poisonous gases. Then astronomers predicted that it was going to pass closer by Earth than ever before. People thought, is it going to collide with the Earth? Then it turned out we were going to pass through its tail. People immediately went, wait, there’s poisonous gases in it. The whole scientific community banded together and said, nothing is going to happen. Apart from one guy who said, we’re all going to die. And everyone listened to him.

AD: I can see that happening.

RM: People have always been suspicious and wary of comets. It’s always been a portent of evil and great change. Then two weeks before the comet was due to go past, King Edward VII died. He’d been ill for months, people knew he was going to die, but it didn’t matter. It was confirming everything that people were afraid of, and triggered this enormous worldwide panic. There were riots and stampedes. A lot of people died. And then, of course, the comet went past, and nothing happened.

Those poisonous gases were my way into this locked room murder mystery. In the book, I imagine that there’s a Viscount of World’s End, which is a remote tidal island off the coast of Cornwall that I’ve invented. He believes the only way to survive these poisonous gases that are going to flood the atmosphere and kill everything that breathes is to make his mansion completely airtight and sealed from the outside world.

So he blocks up every doorway, seals up every window, takes every guest and member of staff and shuts them inside their own individual rooms. The plan is that they will be the only people to survive this thing that’s going to wipe out every other person on the planet. But in the morning, the only person who’s dead is him, found slaughtered inside his own locked and sealed study, with his beloved family crossbow, in a room that nobody entered or left.

AD: You can prepare for the end of the world, but there are some things you can’t prepare for.

RM: It’s just that. The more I learned about the Edwardians—it might be confirmation bias, you look into history and you see what reflects back—but it’s a period of time when everybody was arguing with each other almost constantly. There was a sense in the background that something really bad was about to happen.

Nobody knew what it was, but everybody was kind of freaking out about it a little bit right up until the point it happened. I think in the Victorian era, and to a lesser extent the Edwardian era, a lot of progress was pushed along by very rich men doing whatever they wanted. That feels relevant.

AD: It sounds like part of the book was you coming up with this idea and then having to research this period. How much research was involved and how much of that did you expect?

RM: It was more than I expected. I’ve written a historical book before. There was a book that hasn’t been released in the U.S. before and it’s going to be released, I think next year, called The Midnight Guardians. It’s a children’s fantasy quest that’s set during the Second World War.

So I knew from experience how much work is involved—and then how much of it you just throw away—but I had underestimated how much research I needed to do. Because it’s not even just that it’s a book set during that period of history, it’s a book set in a manor house during that period of history.

I really underestimated how much research I was going to have to do around how houses worked. It’s a locked room mystery, so they never leave this house. The running of the house is going to be key. That’s going to be the building blocks of every single piece of plot.

Also, you have to go into research in this very disciplined and careful way, because you go off on these tangents and rabbit holes. The most annoying thing is that every single one of those tangents and rabbit holes, at the exact moment you’re like, this is a waste of time, that’s when you stumble upon one tiny nugget that is so useful. It’s not necessarily worth all of that effort that’s gone into it, but you can’t say no to it.

I think I’m getting better at research. I’m becoming more controlled in terms of how I do it. In fairness, with this book, I think it was three full rewrites before I got to a point where both me and my agent thought we could submit this. It’s working in the way that it needs to. I made a lot of missteps before I got it right.

AD: As far as those three rewrites, was it a question of getting the characters and the voices right? Was it a question of fine tuning that Swiss watch aspect of a good locked room mystery?

RM: Weirdly, the mystery and the mechanics were always in in reasonably good shape. The biggest mistake I made, the first draft in particular, was I was so excited to be writing an adult book after fifteen years of writing for kids, I was like, I’m gonna throw everything at this. I get to use all these metaphors that I can’t normally use. It was just a mess.

The best example that I can think of to describe what happened was that episode of Friends where she makes a trifle, but there’s two pages of the recipe book stuck together, and so half of it is a shepherd’s pie. I wanted to write this book, but also this book, but also this book. I was losing sight of the fact that what it needed to be was a fun, fast, smart murder mystery. I was missing the fun.

The other thing that took a long time to get right, and I think that the two things are related, was the narrative voice. The book is told from the point of view of nineteen-year-old Stephen Pike, who is the Greg from Succession that I mentioned earlier. He is a young under butler on his first day of work at World’s End when everything happens.

Getting his voice where it needed to be took a lot of work. I just couldn’t get it quite right. I just had this voice in the back of my head getting louder until finally I listened to it. The voice said, he is you. If you just accept that he is you, and if you write it as you, then this will be a lot easier. I went, fine, and then did it.

Miss Decima Stockingham– the Queen Victoria in that metaphor—was easy to write. She sounded pretty much exactly how she was meant to sound from the very first draft. She is the Viscount’s elderly aunt, who is kept more or less locked in a corner of the mansion for her safety and others. She is a secret octogenarian genius with a foul temper and a foul mouth.

I wanted to do a sort of Holmes and Watson pairing. Stephen Pike is the Watson who’s helping this absolute genius, who is the only person who can solve this mystery. She was easy and he was difficult.

AD: I kept thinking of them as a Nero Wolfe and Archie Goodwin pair, just because she can’t get around very much. So often she says, I need you to get this, talk to this person, test this, and bring everything back to me.

RM: I got in trouble for this quite a lot with editors. They were like, the whole point is they’re a detective pair and we want to have the pleasure of hearing them interact, but you keep sending him off on errands. She’s never there. I’m in the middle of the third draft of the second book, which will be out next year. I’ve got this problem again. I need to keep them together. That’s the whole point. But it’s also tricky. It’s just so easy to send him on an errand.

AD: I get that. The two of them together are very entertaining. But you touched on this earlier, talk about the language of the book and how you wanted the characters to sound.

RM: Quite early on was I was thinking about books that I had read that had been written in 1910. The History of Mr. Polly by H.G. Wells was one. He writes in this very elevated, odd way on purpose. I thought, I don’t know if I want to have my characters speaking like that.

I also knew very early on that I wanted one of the elements of Miss Decima’s character to be that she has this incredibly foul mouth and she swears a lot. I knew I was going to have to defend it. I did tons of research into swearing. There’s obviously a lot of debate around it. There’s one guy who’s considered the expert on the F word. There’s the way people would have written and the way they would have spoken. We’ve only really got access to one of those things.

I think people treated the written word with a much, much, much higher regard than we do now. People would not have written swearing. He worked out there were two places where they would have written it. That is court documents and Victorian pornography. Those are full of the F word. Once you go like further back into the history of swearing and the F word in particular, it’s so fascinating.

Miss Decima is a woman of the Victorian era. She’s in her eighties. A woman like that would not have behaved like that. She wouldn’t have spoken like that. That’s part of her character. She is absolutely determined to disrupt absolutely every single impression that people would have of her. I wanted a character that does that both for the reader, but also for the characters in the book. She’s completely unmanageable, and completely shocking.

I am quite proud of the moment when Stephen meets her for the first time in the book, because at that point, she’s been built up as this feared character. The exact moment where she swears in front of him for the first time is the moment that I wanted the reader to go, oh! We’re doing that? All right. Also, I do find swearing fun and funny. That is my problem and I’ll channel that juvenile attitude into my job.

AD: As you said, she doesn’t care and refuses to put on airs, but she’s also presenting in this way to other people. You can see in the book where she stops presenting this front to Stephen the way she does to others.

RM: I liked the idea of a character who has truly stopped caring about how much they upset people and how difficult they are. I wanted to have a character that has those shades of grey. The more that you find out about her, and about her situation and her past, there’s an enormous amount to sympathize with her.

I hope that people will read it and go, well, I’m not surprised that she acts like this, and good on her for doing this. But she is also a very selfish person. She hurts people around her without really thinking about it.

That’s the kind of thing that it is a lot harder to get away with when you’re writing for children. It was one of the things that was most appealing of writing for adults. They can handle that. You can be behind a person who behaves appallingly. You can be rooting for a character without necessarily approving of all their decisions.

I think, to some extent, the same would go for the character of Stephen, who’s quite prim and a bit of a goody two shoes. I think at times he will exasperate the reader. I like the fact that they both bring out a little bit of each other that they wouldn’t have otherwise experienced.

AD: Stephen is completely out of his element.

RM: It’s useful, taking a complete outsider and putting them in a ludicrous situation. That a way of explaining what is ultimately a very complicated idea.

AD: As you said, Decima doesn’t really care anymore about what people think, which is both her strength and her great weakness, because it means that she misses a lot.

RM: It’s exactly that. I’d been writing under contract for about thirteen years. So every single book, pretty much, was was bought from me and then I started writing it.

The last time that I’d sat down and written a whole book from start to finish, without knowing if it would ever get bought, was the very first time I sat down and wrote a book. This is that again. Taking this leap into the unknown, just on the faith that this could work. I was terrified. I’d never written a murder mystery before. I had no idea if we were going to send this book out and I was just going to get laughed out of town.

We got a really amazing response when this went to publishers, but I also got an amazing response to the character of Miss Decima in a way that I wasn’t expecting. The book’s been out in the U.K. since October last year so I’ve met lots of readers, and they really respond to her.

I think there’s an element of kind of wish fulfillment of wouldn’t it be so amazing to truly not care about upsetting anyone around you in any way? It does speak to people. They they don’t want to do it, for good reason, but it’s very nice to read about people doing it.

AD: Yes and she seems to realize at the end, maybe I need to rethink things a little. Maybe I’ll be a little nicer and open going forward.

RM: She gained some humanity. This is the the first in a series. I think I mentioned earlier I’m writing the second one. I want that changing dynamic and how they improve each other ongoing throughout the books, without losing the fun of having people behaving quite badly.

In some respect has so much more power than he does, because she is rich and he’s poor, but also he’s a man and she’s a woman. A huge amount of what she suffered in her life is because being a woman in Victorian England, you’re very powerless. Even if you happen to have loads of money. That’s something I want to keep exploring throughout the books. This is during a period of time where all the ways that Victorian society functioned was unraveling a bit. What was expected of women was changing. People from poorer backgrounds were demanding more fairness and a better distribution of wealth.

I think setting their dynamic within that is interesting and hopefully people will keep coming back for more.

AD: She’s no longer locked in a corner of a remote manor, so she’ll probably become nicer just because of that, but I feel like she’ll find enough things in Edwardian society to anger her.

RM: Exactly! Actually one of the edits that I have been getting back on book two has been, make her a bit nicer. I thought I did! [laughs] Every draft I think I’m making her nicer. Maybe that’s a bit revealing about my personality.

AD: Those are also the laugh out loud moments that we enjoy.

RM: I would say one of my weaknesses as a writer is that when I read a book and they push the plot along without having people argue with each other I’m like, wow. I didn’t know you could do that. My go-to how do you get your characters from A to B will be two people squabbling. You don’t have to do that, but there’s only one way to learn that and that’s by reading tons of murder mysteries. Which luckily for me I get to do now because it’s my job.

AD: Ross, again, you managed to condense so much information about the period and make it incredibly entertaining. Which is so much more enjoyable to read than it is to research, I know, but the book was such fun.

RM: The more I learned in particular about the way that those houses operated, I find it completely mind-blowing. The fact that the class system was so just huge and rigid and watertight. There was even a class system within the servants. Who you were allowed to speak to, and how you referred to each other, and who got to use first names, and who got surnames.

I didn’t know any of that. I knew a little bit. I guess people are a little bit more well-versed in it since Downton Abbey was a massive thing. It’s just crazy to me. This whole ecosystem operating in this one house. People must have thought that that would last forever. How could it ever end? And it just ended so quickly.

There’s a reason why those Golden Age murder mysteries continue existing. It’s a lot easier to write a mystery in a formal society where there are expectations. If you’re this kind of person then you behave in this way. If you’re this kind of person then you do this. In Agatha Christie books you will have these moments where somebody will say, well, the colonel always had his soup at five o’clock in the evening precisely, and so when it was 5:07 and he hadn’t appeared in the dining room, I thought that was unusual.

People do not behave like that. If you tried to set a murder mystery now and you had people doing that you would have a very difficult time doing it, but you accept it in a book that is set in 1910, 1920, 1930. Then you get to play with those expectations. It’s just tons of fun.

***