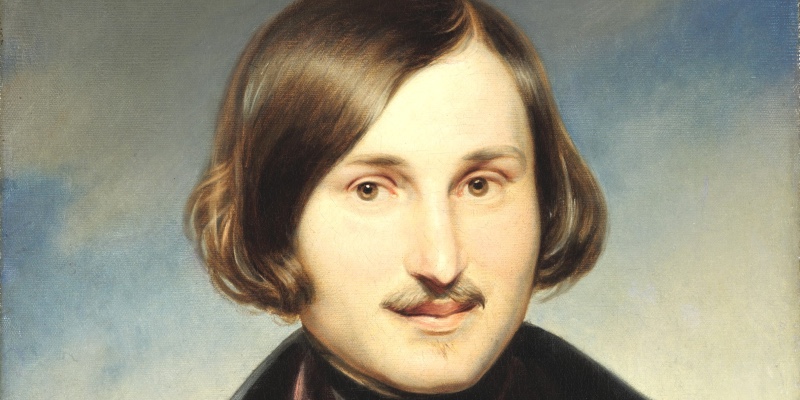

When I was a kid and guys my age were reading books like The Hardy Boys or Doctor Doolittle or Johnny Tremain (this was way before Harry Potter or Stephen King), I discovered a strange Russian writer named Nikolai V. Gogol. If you don’t count A Wrinkle in Time, the first “adult” fiction I ever read was Gogol’s short story “The Nose” (1836) — in a battered paperback I found on my older sister’s bookshelf.

I was immediately captivated by the storyline, in which an ordinary civil servant wakes up to find the nose on his face missing; the nose is found in someone else’s loaf of bread, only later to be found striding down the streets of St. Petersburg dressed like a civil servant of an even higher rank than the guy whose face he used to be on. Sold me, even though I didn’t get much of its subtleties. Next I read Gogol’s long short story, “The Overcoat” (1842), about a poor government bureaucrat in St. Petersburg named Akaky Akakievich whose co-workers tease him about his threadbare coat. He saves and saves his wages until he has enough money to buy a beautiful new one. Naturally, he’s mugged on the street and thugs take his overcoat. Akakievich seeks help from his superiors but is mocked and rebuffed. He falls ill and dies. Soon a ghost is spotted in the city, stealing overcoats from the citizens of St. Petersburg. It’s a weird, original, inventive tale, which Vladimir Nabokov called “the greatest Russian short story ever written.” I just thought it was an excellent crime story.

Not until I was a lot older did I read Gogol’s dryly comic novel Dead Souls (1842), about an aristocrat named Chichikov who comes up with a great scam: He offers to buy the names of dead serfs from rich landowners to acquire a vast, if fictional, estate. It’s hilarious and ridiculous and entertaining. And scaldingly satirical about the pretentiousness of the Russian middle class and bureaucracy. By the time I was in college, and a Russian major, I finally got it.

Gogol was not an author most of my non-Russian-major classmates were familiar with. One Russian writer they’d all heard of was, of course, Fyodor Dostoevsky. And it’s Dostoevsky who’s generally considered to be the enduring influence on crime fiction and the detective novel in the West: particularly his Crime and Punishment and Notes from Underground. Which is interesting because Notes is a novel without a crime, and in C&P we know who the murderer is — spoiler alert: it’s Raskolnikov — from the beginning. (We just don’t know his motive.)

In his essay on Joseph Frank’s translation of Dostoyevsky, David Foster Wallace focuses on the chief criminal investigator Porfiry Petrovich, “C&P’s ingenious maverick detective . . . without whom there would probably be no commercial crime fiction with eccentrically brilliant cops.” One academic, Mark Knight, argued that Porfiry Petrovich inspired G.K. Chesterton’s detective, Father Brown: “the investigator who solves crimes by a combination of incongruity, perspicacity, intuition and surprise, besides more conventional police methods, without resorting to sensational tactics or egoistic posturing.”

Could be; I haven’t read enough Chesterton to have an opinion. But Notes certainly gave us what’s sometimes called “psycho noir,” in the twentieth century, where the disturbed, homicidal protagonist rants and justifies his actions at twisted length, mixed with brutal social observation. It gave us Jim Thompson’s Lou Ford from The Killer Inside Me (Thompson, who was captivated by Dostoevsky, was labeled by one noir expert “a dime-store Dostoevsky”).

The anonymous narrator of Notes declares, “It is best to do nothing! The best thing is conscious inertia! So long live the underground!” He refuses to become a worker in the “ant-hill” of society. The great Charles Willeford, Miami’s master of weird comic noir of the 1980’s, once pointed out in an essay that “the immobilized hero” in all noir fiction came from Dostoevsky’s Notes: “the frenetic, endless, and impossible attempt to escape from the restriction of the self, the personality, into a freedom that simply does not exist.”

But Crime and Punishment and Notes from Underground (and The Brothers Karamazov) didn’t come from out of nowhere. Dostoyevsky was an attentive reader of Edgar Allan Poe: he wrote the preface for the first Russian translation of Poe’s crime fiction. And the eminent scholar of Russian literature at Harvard, Donald Fanger, has established that Dostoyevsky was also hugely influenced by Gogol. Gogol’s prose, comic and brilliant, sometimes absurd, burst like a supernova on the Russian literary scene in the mid-nineteenth century and left a powerful impression on his contemporaries and his successors. One dramaturg, Laura Henry Buda, called him “the godfather of Russian literature,” claiming that “Gogol revolutionized Russian prose.” The hero (or protagonist, anyway) of Dead Souls, the swindler Chichikov, thunders through the streets of St. Petersburg in his carriage, in a stream-of-consciousness daze, prefiguring Raskolnikov from C&P wandering through the Haymarket, deranged thoughts coursing through his head.

If you consider Dostoevsky a crime fiction writer (and I’m happy to claim him), then Nikolai Gogol was, you might say, the O.G. crime and suspense writer. One of his finest stories, “The Portrait,” was first published in 1837. (After a spate of lousy reviews, Gogol rewrote it significantly, republishing it in 1842.) It’s a Faustian tale of a struggling artist named Chartkov who buys a strange painting of a money lender with eerily lifelike eyes. Later the picture’s frame breaks open and dumps gold coins before Chartkov, making him rich and eventually the toast of fashionable society, where he squanders his talents, heading for the inevitable crash. But the painting of the money lender keeps getting passed down from painter to painter, destroying each of their careers and lives. It calls to mind Oscar Wilde’s novel The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890). Where Chartkov wants popularity, Dorian Gray wants eternal youth. Both gain what they seek from the hypnotic, malign power of a painting, and it becomes their ruin. Whether Wilde read Gogol’s story is unknown, but “The Portrait” was first published in English translation in 1847.

Gogol cast a spell on Dostoevsky, who in turn cast his spell on a whole generation of Russian crime writers from the 1860s and onward to the Russian Revolution in 1917. One of the influential contributions, published in Dostoevsky’s magazine Epoch, was a strange and powerful 1865 novella by Nikolai Leskov called Lady Macbeth of the Mzinsk District. It’s a story of passion, adultery, and murder, told in a strikingly conversational voice, and it’s like a crude, early draft of James M. Cain’s Double Indemnity.

There’s a great saying, famous in Russian — “We all came out from under Gogol’s Overcoat” — apocryphally attributed to Dostoevsky, but accurate nonetheless. Gogol’s wildly surreal, yet at the same time realistic narratives gave rise to Russian crime fiction of the late imperial era and to Dostoevsky . . . and so on down the line to Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler and James M. Cain and on to today.

To be sure, literary traditions aren’t like a flow chart of influence, or a dynastic line of inheritance. They live in our heads—a web of connections that forms as readers and writers engage with stories in their own way. Joyce Carol Oates once called James Ellroy the “American Dostoevsky,” to which Ellroy replied, “I’m the American Dostoevsky, and I’ve never even read the guy.” But he wasn’t exactly rejecting the tribute. The dialogue between past and present is constant. In the end, we find what we need to make what we’d like—like Akakievich’s warm overcoat. And if it’s a good overcoat, there will always be others waiting to take it.

***