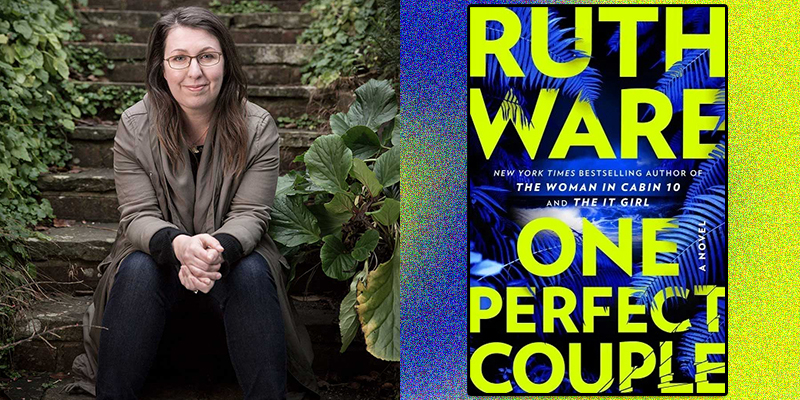

Best-selling British author Ruth Ware is back with another gripping tale, this time whisking us to a tropical Indonesian paradise that quickly turns nightmare in her latest, One Perfect Couple (Scout Press, 5/21).

Facing the uncertain future of her research career, scientist Lyla agrees to follow her aspiring actor boyfriend Nico to a desert island to participate in a brand-new reality TV show. In One Perfect Couple, five couples will compete, collaborate, and face eliminations, until one winning pair remains, crowned “perfect couple.” The show’s production appears sketchy to Lyla from the get-go, but she knows this opportunity matters to Nico and she could use the break, so off they fly to Jakarta and meet the other contestants. Not long after the competition begins, a massive storm sweeps the desert island where they just got settled, and the contestants become trapped there in the middle of the Indian Ocean, with no certainty of rescue. Worse: it soon becomes clear a killer walks among them.

While One Perfect Couple has been described as harkening to Agatha Christie’s classic And Then There Were None, it leans more toward high-tension thriller than traditional mystery. As the island’s inhabitants get picked off one by one, Lyla and the others race against time, against the elements, and against the killer among their stranded lot. The central question posed by this page-turner becomes not so much “whodunit?” but “who will survive?”

While One Perfect Couple has been described as harkening to Agatha Christie’s classic And Then There Were None, it leans more toward high-tension thriller than traditional mystery. As the island’s inhabitants get picked off one by one, Lyla and the others race against time, against the elements, and against the killer among their stranded lot. The central question posed by this page-turner becomes not so much “whodunit?” but “who will survive?”

Ware’s suspense and sleight skills are on full display here, along with some psychologically astute character development, making One Perfect Couple a riveting read. If an audiobook is more your cup o’ tea, narrator Imogen Church, who reads all of Ware’s novels, gives a riotous, multi-voiced and -accented performance that will keep you tethered to your headphones.

I had the pleasure of a long Zoom chat with Ruth Ware, stateside for her book tour. We discussed the psychology of truth and manipulation, the mass appeal of the crime genre, and her approach to crafting her trademark thrillers, among other things. This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

This book features reality TV contestants stranded on a deserted island. How did the idea come to you?

I was doing an event with British thriller writer, Gillian McAllister, and we started talking about reality TV. I said it was a miracle more people weren’t murdered on reality TV shows because the tensions were so high. And Gillian said, “Sounds like a Ruth Ware book!” I kind of laughed it off but eventually when I sat down to write, I thought actually it would make a really good book.

I was completely addicted to the Big Brother when it first came out in the UK, but I drifted away from reality TV when it became less about ordinary people doing this kind of social experiment and much more about people who were in it as a stepping stone for their career—influencers or models or people who were doing this to become famous. But then, a couple of years ago, Traitors came out in the UK, and it featured exclusively regular people, a cross section of society that I hadn’t found on a reality TV show before. The premise is that twenty people are shut up in a country house together: “faithfuls” who cooperate to build up the prize, which will be split between them if they get to the end, and three “traitors,” and if one of them makes it to the final day, they scoop the lot. There’s an elimination every night and it’s very brutal. One of the fascinating things about Traitors is that it shone a very unforgiving light on how incredibly bad people are at knowing when someone is lying to them. The first people who get eliminated are the most honest. And the traitors are largely picked [to stay] because they’re very emotionally intelligent people, very good at understanding what other people want to hear.

Obviously the show in One Perfect Couple ended up being much closer to Survivors or Love Island. But the Traitors element that survived in the book is that the majority of people are working together for the good of the group, but a few are not and they are telling the other contestants what they want to hear.

Your heroines are often ordinary women thrust into extraordinary situations. Your narrator, Lyla, is a bit like a fish out of water on the island (forgive the pun), the nerdy girl next-door when everyone else is gorgeous and glamorous. Why did you choose to make her an outsider?

Partly it’s a nice shortcut to have a point-of-view character who is an outsider because it gives me the chance to remark or explain things to the reader. There’s a lot that Lyla notices about the reality TV show industry that [an insider] wouldn’t have found remarkable and therefore wouldn’t have brought to the attention of the reader. Lyla is also a scientist. My husband is a scientist and his career has taken him on a path not dissimilar to hers, working on experiments and post-docs. Scientists came out of the COVID pandemic as rightly celebrated, but also as sort of unsung heroes in that there’s a huge amount of misunderstandings about how science works. It made me want to write something from the point of view of a scientist.

About a third of the way through it, it struck me how similar being a good scientist is to being a good detective. Lyla is someone who’s constantly asking questions, and she doesn’t always like the answer that she gets. But because she is a good scientist, she knows that she has to go with the data, because her primary duty is to the truth. On the island, she continues to ask the difficult questions and try to dispassionately assess the data and give a truthful answer, even when that answer is not the one that she wants. A good detective obviously has theories when they go into a case and they have something that they want to prove, but a good detective should be looking at the evidence, and if it disproves their theory, they have to be true to that.

So much of reality TV production is about creating a story the producer already wants to show and [they] have to take the raw material of footage and shape it, but that is entirely antithetical to what Lyla as a scientist believes. Having her in that role was an interesting way of exploring what duty all of us really have to the truth.

As in any reality TV show, alliances quickly form in One Perfect Couple. At one point, some of the women band together. This novel feels feminist in that women are shown to be self-sufficient in a difficult context often assumed to require male strength. Tell me more about this narrative choice.

Criticism that I sometimes get online about my characters is that they’re a bit incompetent or useless. And I always feel fiercely defensive when people say that because I think my characters are in a pretty horrific situation, often facing life or death, and realistically, I would be an absolute basket case in that situation. But we hold fictional characters to a higher standard and expect them not to make poor choices. So I guess in this book, I wanted to show a bunch of characters making the best of an incredibly shitty situation and doing everything they can to survive, help each other, and overcome.

Quite a few of those people end up being women, but that wasn’t an intentional decision. I didn’t sit down and think “I want to show girl power.” I think partly, I am just more interested in women’s stories. One of the first books I ever wrote growing up was a thinly veiled version of Ursula Le Guin’s Earthsea trilogy, because I loved it but was quite peeved that the main character throughout is a man. So I wrote my own version that had a young woman at the center of it. I think in some ways that’s what all my books have.

In this novel, you take on problematic or toxic masculinity head-on. One character is an Andrew Tate wannabe with millions of YouTube subscribers. Another one lives off his girlfriend while he tries to make it as an actor. Under pressure, some of the male characters turn violent, vengeful, or cowardly.

The men are flawed, sure, but I think the women are flawed as well. The premise of the reality TV show is about finding one perfect couple. As part of that, I wanted to explore what makes a perfect couple, what turns relationships toxic, how many people look perfect on the outside but when you are a bit closer to their dynamic, you can see very deep-seated problems. I don’t plot my books a whole lot. So I started writing this one with the opening scene of the man and the woman fighting in the sea. And I always knew that was going to be the emotional climax of the book. Eventually I knew who the couple were and why they were [in the water]. But beyond that, I didn’t know who was going to survive, who else was going to be on the island at that point.

Obviously, I’ve never been in a situation as high stakes as that, but often if you are in a difficult situation, even something as minor as pitching a tent in a howling gale, there are interesting gendered differences in how people approach it. Women do tend to be more cooperative and “is everyone happy with this?” whereas men can be very goal-focused and competitive about it. There are scenes early on the island where the men are more interested in butting heads and establishing who’s going to be the boss on the island, whereas the women have completely different priorities.

Fundamentally, I’m not very interested in writing about perfect people. And I think that’s probably reflected in the title: the idea of there being any perfection is a fool’s errand. So, yes, all my characters are flawed and difficult and sometimes quite unlikable, and that’s part of what I love about them.

Claustrophobia and alienation are a recurring theme in your novels. In Zero Days, Jack is on the run, cut off from everyone she knows in order to survive. In The Woman in Cabin 10, Lo is trapped on a boat. Here the characters are stuck on an island with a killer. What draws you to these oppressive contexts?

All my books are about my own fears and phobias. My personal nightmare is being trapped in a stressful situation with people I don’t like and can’t get away from. I am not physically super claustrophobic but I am emotionally claustrophobic. So I think I keep putting my characters through that because it’s the most stressful situation that I can imagine. And yeah, for poor Lyla, being stuck on an island is bad enough, but with a bunch of people that she really has nothing in common with is her worst nightmare.

I love writing novels with a very small cast of characters, because it makes you much more creative. If you set these very strict limits at the beginning — you can’t get out of this environment; you can’t get new characters in; you can’t get any characters out; you can’t parachute in a detective at the 11th hour — you only have the resources that you give yourself at the start, to see this through to its conclusion. When you have a small cast of characters, and you are using them for every aspect of the plot, it enables you to dig much more deeply into those people. So you find out much more about them. You see them under much more stress.

The psychological thriller genre could be considered an odd type of escape in our stressful era of pandemic, ecological, and economic hardships. Why do you think crime novels are so massively popular these days, particularly among women?

Crime and thriller novels are in many ways a very reassuring genre to read. In World War II in the UK, when we had paper rationing, and publishers were limited in what books they were allowed to put out, certain authors were considered national priorities. One of those was Agatha Christie because her books were felt to be very good for morale. When we are in incredibly unsettling, globally terrifying times, it can be comforting to read a book where a terrible thing has happened, but within fairly safe parameters and, 99.9% of the time, there will be some sort of restorative justice. Things will be okay; you will find out the solution to the mystery, there will be some balancing of rights and wrongs at the end. I think that’s an immensely comforting thing to read. It’s why people read romances too, that similar idea of having fixed expectations of where [the genre] is going to go and a sense of comfort when you get to the end. Hopefully you were surprised along the way and wrong-footed and delighted by various aspects. But there is a sense, when you read most crime novels, of being in fairly safe hands.

Women make up by far the biggest audience for true crime podcasts. And that is always cited as extraordinary, that women should want to immerse themselves in this genre that’s all about terrible things happening to other women. But I think if you face those demons, you can cope with them better. You are arming yourself with knowledge of a cautionary tale. Picking your way through the world [as a woman] is inextricably bound up with caution and fear and a knowledge of how things can go wrong. Any woman who has walked home from the pub alone after a late night would agree with that. It’s about making judgment calls, sizing people up, thinking whether to take a risk. It’s about a sense of fear and self preservation and protection. And reading about that in a heightened form in the safe environment of a book can be very cathartic.

Do you have any craft tips for writers working in suspense or mystery?

I think writing is incredibly hard to teach because so much of it is instinctual. But the tip that I often [share] is the idea of giving your readers a reason to turn the page. Usually that is a question that they want answered or a mystery that they want to solve. Crime writers have an inbuilt advantage with this because there’s always a question at the beating heart of our books, usually who did the murder. But one question will not sustain you throughout the whole book. So it becomes a [matter] of giving little teasers of information and then answering some of the questions but withholding others.

There’s a great example of this in the novel Gone Girl, at the end of one of the first chapters, the narrator Nick says in an aside to the reader, “That was my fifth lie to the police.” And you’re like, excuse me? What are the other four lies, and why is he lying? And now you’re going to have to turn the page to find out what is going on. It was so genius and a really good example of how little bits of mystery and misinformation might be absolute catnip to the reader. There’s a few examples of that in One Perfect Couple, mostly to do with the diary entries and the radio calls that are scattered throughout the book and sort of tease you with questions. I think it’s a really good test for any writer to get to the end of a chapter and think, what does the reader want to know? And how much of that am I going to answer in the next chapter?