One day in the summer of my sixteenth year I was riding around my hometown in my best friend’s car. It was a jet-black sports car with flashy rims and a spoiler wide enough to be an airplane wing. We were listening to music, talking about the girls we liked and the dreams we had as young black boys who were trying to learn the ways of men.

I was the one who first noticed the blue lights.

My friend didn’t panic. We both knew he wasn’t speeding. We weren’t drinking and neither one of us smoked weed. He pulled over and lowered the window then put both his hands on the steering wheel. I put both of mine on the dashboard.

This was the way our parents had told both of us to interact with the police. The conversations had happened at different times, but the content was the same.

“Don’t talk smart.”

“Keep ya hands visible.”

“Tell them you are reaching for your license.”

“Do whatever they say so you can come home.”

These words, delivered in quiet tones and hushed voices, had never actually seemed real to me. I hadn’t had that many interactions with the police. I was a rambunctious kid, but pretty grounded. I was in many ways a nerd. I liked to write. I read voraciously. I even entertained becoming a private detective or an FBI agent. I knew—intrinsically, as most people of color or people below the poverty line know—that interactions with the police can only really go in one of two ways.

Very good or very bad.

But I still didn’t think about those interactions in respect to myself as a black kid in the South. It wasn’t real to me, in the same way mortality or infirmity isn’t real to any sixteen-year-old. Those things are just words to the ears of the young.

The police officer came up to the window and asked for my friend’s driver license. My friend obliged. Then he asked for mine. I asked what I thought was an innocent question.

“Why do you need my license?”

In the few seconds between when the question was asked and when it was answered I watched this officer, a florid-faced white man who I vaguely recognized as a someone who had gone to school with my older brother, transform before my eyes. His countenance went from mildly disinterested to enraged.

He screamed at us to get out of the car. In the middle of July, he made us both put our faces to the hot asphalt. He tore into my friend’s car without asking for permission to search it. He accused us of being drug dealers, thugs, criminals of the worst order. When I protested that we were none of those things he got down on one knee and put the barrel of his gun against the back of my head.

“You’re whatever I say you are.”

In that moment, mortality went from just a word to a reality. As I lay there with dirt and gravel sticking to my face, I realized that this man who had barely graduated from high school, who still came to football games and hit on the cheerleaders, who expected and received free coffee and donuts at every gas station in town, who had, at best, six weeks of training held my life in his trembling adrenalized hands. He could shoot me; say I’d made a move for his gun and get away with it. And neither my mother’s tears nor my father’s cries would make a difference.

It’s said by more than one person who seeks to address the issue of policing in this and other countries that we shouldn’t focus on the bad apples. They repeat that adage again and again, but they neglect to finish it.

One bad apple can spoil the bunch.

The comedian Chris Rock has a routine where he talks about how there are some jobs where you just can’t have a bad day. Pilots, doctors, and cops.

We are indoctrinated from an early age to treat police officers with awe and respect. We are implored to back the blue. Officer Friendly is a character in primary books. Television, films, and books are full of stories of heroic cops bucking a system that doesn’t work and taking matters into their own hands, to hand out justice and uphold the law. Police officers lay down their lives to protect and serve. And in a perfect world that would be the end of the conversation.

But the world isn’t perfect, and we all fall short of grace.

There are police officers who I truly believe want to do the right things. They want to help the community. Protect the innocent and do all the heroic things they imagined they would do when they first put on the uniform. Unfortunately, in most cases the deck is stacked against them . . . and us.

Many modern police forces arose out of the slave patrols of the 1850s. After the Civil War, police forces were organized to control not only former slaves but anyone the majority deemed unacceptable. As the years rolled on many police departments experienced a shift in their mindsets. For many, protect and serve became terrorize and subjugate.

The actions of police chiefs in the South like Bull Connor, or officers like Jon Burge of the Chicago Police Department, made a mockery of not only the law but basic human decency. These men and other officers like them killed, tortured, and embraced corruption with impunity.

There is a tendency to push back against this idea by those who would seek to defend not just the police as an entity but policing as a necessity. “Not all cops are bad” they will cry. And they are correct. But to paraphrase Mr. Rock, Just one bad cop is one too many. Just one bad cop who feels he or she is a warrior in a near mythological battle with evil or, worse yet, feels that they are not beholden to any rules is the most dangerous person on the street. More dangerous than anyone they might arrest. Because they hold our lives in their hands. And many times, they are not careful with that awesome duty.

I think the conversation around policing has to change. The current structure is breaking down under the weight of its own hypocrisy. To quote Yeats, the center does not hold. We cannot continue down this path of idolization and impunity. Too many have died, too much blood has been spilled. I won’t pretend to have the answers, but I am fiercely committed to asking the questions. My life and the lives of too many others depends on it.

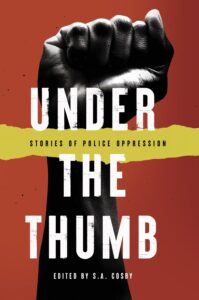

The stories in this anthology are an attempt to change that conversation. In ways both subtle and overt, they ask the questions we all should be asking. How do we reclaim our power as a people? How do we hold the police accountable? What does it look like when those to whom we give great power don’t understand the great responsibility that such power entails? And how do we move forward?

I am so proud to have collaborated with Rock and a Hard Place Press on this collection. These stories are ferocious and introspective. Powerful and heartbreaking and harrowing. They are raw and honest and most important of all, they are fearless. They speak truth to power in a way that only the very best literature can.

In the words of French philosopher Voltaire: “If you want to know who controls you, look at who you are not allowed to criticize.”

Or more succinctly in the words of Malcom X: “I’m going to tell it like it is. I hope you can take it like it is”

These stories encompass both ideals.

S.A. Cosby,

Guest Editor

November 2021

P.S.—that cop that pulled me and my friend over? He retired after twenty years with a commendation from the governor.

___________________________________

From S.A. Cosby’s foreword to Under the Thumb: Stories of Police Oppression, published by Rock and a Hard Place Press, 2021.