Noir is a form I came to love when I began living in New York City, but it’s a feeling I first felt in Sacramento. I grew up in the suburbs east of Sacramento in the 1980s and my father worked downtown. We’d take the bus into the city, so fragrant with its million trees, so empty of pedestrians in many places; it was a regular Saturday event, when my dad would go in to work on weekends, writing grants for the family service agency he ran. The stony silence around the capital. The dry soft air. The prevalence of older people, and old cars, like the ones you’d see in black-and-white movies. It all felt mysterious and large, and full of portent.

The capitol area was where adult things happened; my three great aunts lived around there. They resided in apartment buildings, and drove great big Oldsmobiles. Two of them had been single a long, long time. Their mother had been German and every time we piled into our own smaller car and drove west to visit them, especially Rose and Louise, I felt like I was simultaneously going back in time and farther out to sea—in a world where more complex things happened.

I wasn’t ignorant of this world. I read the newspaper because I delivered it. Every morning around five a.m., my older brother and I would stumble into the garage and begin counting and folding copies of the Sacramento Bee. Some mornings both of us would scan the headlines—even as ten- and eleven-year-olds. Then we’d pedal out into the soupy early morning dark, our bikes weighed down by newsprint, our heads full of stories of the day: earthquakes, double-overtime losses in basketball, the occasional murder, and sometimes a secret pregnancy.

The paper route was more than a job, it was a kind of living map for both of us. We identified houses by who lived where, and by stories we gleaned in the monthly collection visits. There was no auto-pay back then, no tap and swipe. One literally had to go and extract payment every month from customers, some of whom would even dodge a ten-year-old. And so every month, between six and eight p.m., I’d ring people’s doorbells and ask for $8.50.

Some things astonish me as an adult now with a niece the age I was delivering those papers. For starters, I can count on one hand the number of times in eight years I was invited into a house while someone retrieved their checkbook instead of paying with cash. Somehow I was never bitten by a dog, although a few of them all but learned English in their attempt to make it clear I was not welcome. It snowed just twice, and the look on people’s faces who came out after it stopped made me a lifelong early riser. There were skunks everywhere.

Also, people revealed themselves. Sometimes with the door open into a house, I’d hear an argument—the long, grinding argument of an unhappy marriage. I saw people leaving furtively, like they didn’t want to be seen. I smelled what was cooking, or sometimes just sour coffee. Whole worlds of stories piped out during the moments that front door was open, and then it would shut, and I’d go on to the next house.

This book is an attempt to prop a metaphorical door open a little while longer, a way to invite you into a variety of houses and apartments and spaces all over Sacramento, to imagine lives, not yours, or perhaps like yours, as told by some of the city’s most talented living writers. What freedom is here in words: to travel, to visit, to linger, to hear stories from all across the city, and to some degree across time—both Naomi J. Williams and José Vadi set their stories in the 1940s/50s.

This is a book of noir, so the spaces we’re beckoned into here are dark; they are sometimes not even moonlit. In Jen Soong’s story, a woman is haunted by the ghost of the child of a next-door neighbor, or that’s what she thinks he might be—she’s too far gone on drugs she’s been stealing from a pharmacy to know for sure. Meanwhile, in Jamil Jan Kochai’s tale, an ex–police detective from Afghanistan stumbles on a body in the marshes beyond his apartment building; he’s not even sure that’s what it is until two men turn up to secretly bury the man.

The Sacramento River has a living presence in these stories. In José Vadi’s historical noir, the river forms a mode of escape. In Maureen O’Leary’s story, it is the last stop in a woman’s return into the orbit of a chaotic and nefarious friend.

Dangerous dames are a hard theme for noir to carry into the twenty-first century without some rightful critiques. The stories here gesture toward that noir past, but reinvent it. Reyna Grande’s story about two brothers—a priest and an artist, united by their fascination with a sex worker they’ve hired to pose for an artwork—carries an implicit critique of the way women are used to represent ideas men have created about them. In Maceo Montoya’s tale, in which mural artists working in the early Chicano movement fall in love with a new female collective member, the narrator becomes so jealous that a schism develops within the group.

In Nora Rodriguez Camagna’s story, a family living in South Sacramento confronts the risks of coming to this country while being stalked by an entirely different risk. In the story I contributed, a hit-and-run accident triggers a cascade of memories for an EMT worker who had nowhere to turn in a former life.

How a society treats those who are down and out, people who count as its outsiders, can reveal a lot about the way that society actually runs. In a piece titled “A Reflection of the Public,” William T. Vollmann conjures a military veteran who has tumbled out of the housed life and is living in an encampment, where he finds unexpected tenderness in a lover, and in the politically charged conversation of friends. In Janet Rodriguez’s tale revolving around an errant key her protagonist finds in a thrift-store purchase, the act of returning it leads her to an eviction, one she is powerless to stop.

Crime isn’t always about single acts of violence. Sometimes it’s a system devised to perpetuate other forms of violence and disenfranchisement. Two stories here situate themselves in such nexuses—within the law, and within academia. In Shelley Blanton-Stroud’s story, a woman decides she’s going to help her elderly grandmother around the house, and discovers an asset she might want to protect. In “A Textbook Example” by Luis Avalos, a young man studying confirmation bias finds himself in a situation almost predicted by his research: there’s been a murder on campus, and the description of the perpetrator sounds a lot like him.

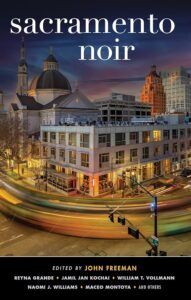

Here is Sacramento in all of its splendor and deep, not-at-all-buried contradictions. A frontier city that quickly used its wealth to gather power. A locale that is somehow not quite sure it is still urban. Darkly compelling, canopied, gusted by river smells, Sacramento emerges from these thirteen stories like a character itself. It’s the kind of place that has sprawled widely enough, and covered enough different landscapes, that it is now many cities, some of which do not interact with each other. Some of which are only remembered in names of neighborhoods which people who once lived there still use with each other: Sakura City. The West End. Broderick. What a joy and vivid dream it is to see these stories here together, between these covers—for all to visit.

John Freeman

November 2024

From Sacramento Noir, edited by John Freemen, courtesy of Akashic Books.