I moved ten times before I turned seventeen. That number doesn’t count temporary moves while waiting for housing, like the time we lived in a hotel on Waikiki for two months. Or the many short stints in apartments, often with no furniture other than the bench seat from our minivan, a television, and some air mattresses. My family wasn’t part of witness protection—my father was in the U.S. Navy.

When you move all the time, you develop a different way of relating to people. You get used to leaving them. You acquire the knack for making friends quickly, but friendships are often shallow. There’s no point in investing when you’ll just have to pick up and leave and never see them again. Your family becomes the constant in your life—no matter where you go, you’ll at least know these people.

When I was in second grade, I discovered another constant: books. Or more specifically, my new friend Nancy Drew. She and her best friends Bess and George solved mysteries, sometimes with the help of her lawyer father, Carson. Nancy was much older than me, incredibly brave in the face of rags dipped in chloroform, and smart enough to unravel any crime. Reading her books opened a whole new world—one I could carry with me wherever I went and escape into at a moment’s notice.

Once I outgrew Nancy Drew, there were other friends waiting for me in books: Jim Kjelgaard’s dog stories like Big Red and Wild Trek, My Side of the Mountain, The Phantom Tollbooth, Alice in Wonderland, C.S. Lewis’ Narnia series, Sweet Valley High. My tastes matured as I did, and although we didn’t have much in the way of teen books at that time, I found plenty of adult fantasy and science fiction to hold my attention. No matter where we moved or what changes life brought, I could always find solace in a book, losing myself in someone else’s story.

My nomadic childhood may be unique compared to many teens’ experiences, but I’m far from being alone in finding comfort and companionship in a story. Ask just about anyone who reads, and they’ll tell you about that one book, or maybe even a whole shelf full, that got them through a particularly trying time of life. Readers turn to books for many reasons, but often it’s escape, the search for hope, and a safe place to confront uncertainty and fear. Perhaps this is even more true for younger readers, who, like teenaged me, turn to books as a way to deal with the difficult things in real life.

But how can authors who are older write for teens in a way that feels authentic and relevant? As adults in a hyper-connected world, we tend to jump on every trend as soon as we sniff one out. We slant our social media posts toward whatever people are talking about at that exact moment, partly because we want to seem culturally aware, but mostly because we think it will help us sell whatever we’re trying to sell. In the case of publishing, we’re selling books. I wish an alternate universe existed where we wrote books solely for the sake of art, and thousands of people read them solely for the purpose of enjoying our art. But the reality is, publishing is a business, and the only way to sustain it in the long run is by making money.

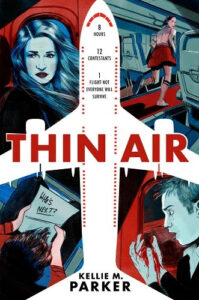

So, we watch what’s happening in the world and what other authors are talking about, and because of lightspeed internet and the immediacy of social media, the next New Thing rides its peak of popularity for two days and then gives way to Whatever Comes Next. Coachella is happening right now? Here’s what musical act vibes with my book. Among Us is trending? Why, my book is Among Us on a plane! (In fact, as my teen son pointed out in 2020 when I was drafting Thin Air, my book is Among Us on a plane. This similarity was unintentional, which leaves me wondering how many of these connections come from a broader experience of the world at a particular time, or in this case, how much the Covid lockdowns impressed upon all of us the idea of being trapped with a killer.)

There’s nothing wrong with keeping up with what’s happening in the world and being aware of trends—and quite frankly, it’s often the best way to catch the attention of the powers that matter when it comes to book sales, like BookTok and Bookstagram and booksellers. But if we rely on following trends as our only means to engage with teen readers, we’re barely scraping the surface of what matters to them. Most social media trends pop up like an American Southwest thunderstorm and vanish just as quickly.

I’ve seen another shift happen in YA publishing since the boom began in the early 2000s: because these books are popular with older readers also, many authors have “aged up” their protagonists to appeal to a larger crossover readership. The result is that often books marketed as “young adult” or “teen” have main characters who act more like twenty-five year-olds trapped in a sixteen year-old’s body. These characters think and respond like adults, and often the issues they face are geared toward adult readers rather than teens. Unfortunately, New Adult as a category has yet to find its footing in traditional publishing, which probably explains why we find these books marketed as YA instead. But we still need books written for teens, about teen issues.

What has made authors like Judy Blume so enduringly popular? Their books aren’t full of the latest slang words or pop culture references, and they aren’t targeting adult crossover readers; instead, these stories find continuing relevance by tackling issues and themes common to teens across generations. We all have to grow up. We all have to navigate our changing bodies, relationships with parents and authority figures, first love, figuring out who we are and what we care about, decisions about our future. The details vary across cultures and places, but so many rites of passage of adolescence are universal.

This fact makes the author’s job both easier and harder on some levels. If you want to know what teens care about, remember what it was like to be that age. What did you care about? What thoughts went through your mind on a daily basis? What stresses and worries concerned you? How can you draw on your own past to relate to what teens face today? On the other hand, unless you’re writing a memoir, you can’t mire your story down with only your own limited perspective and experiences. Those things might make a solid foundation for your protagonist, but you don’t want your book to read like you wrote it three decades ago. So while relying on universal themes, the writer for young adults must also consider what’s currently relevant.

I have the advantage of having three teenagers of my own. They kindly explain to me what words like “bussin” and “afk” and “yeet” mean, so I’m not a completely obsolete relic of the 20th century. (Though I avoid most slang words in my books, because odds are they’ll be out of use before the book even makes it to press.) I also pay attention to my kids and their friends—the things they talk about, how they spend their time, what concerns them about the world and the future. Keeping an eye on news headlines is a good idea too. Not all teens closely follow world news, but they’re guaranteed to have heard about most global concerns through trickle-down means, whether from teachers, parents, or social media influencers. Surveys and scientific studies can also tell us a lot about the state of life for today’s teens, often painting a depressing picture of increasing suicide rates, drug abuse, bullying, and mental health concerns. This generation of teens is struggling in many ways, and they need relatable stories now more than ever. You never know how your words will impact someone else’s life.

When we write books that tap into issues that matter to young adults, we’re offering them a safe place to process what’s happening in their lives and in the world. With the variety of complex issues facing teens today, there’s space in teen publishing for difficult topics too, though these should be handled with sensitivity and authenticity rather than didactics. Teenagers want to think for themselves, not be told what to think. As authors, we have the unique privilege of meeting them where they’re at and creating stories that could become someone’s haven in the turbulent storms of adolescence. It’s a privilege and responsibility we should never take lightly.

***