I imagine writing a crime novel is close to the middle of human experiences ranked by difficulty. It isn’t brain surgery, but neither is it a walk in the park (although, conceivably, you could write a novel while doing either of those things, and I’m sure plenty have). I was fortunate to come from a family that loved books, and lucky to go to good schools, where books were bountiful. I was less lucky in that, when I started writing, I didn’t have much in the way of sympatico teachers, mentors, friends or even, really, acquaintances who knew anything about writing books, finishing them, and publishing them. Which is to say, I learned how to write from reading. One of the joys of my adult professional life is the opportunity to be a friendly and encouraging (if busy, occasionally cranky, sometimes unpleasant, not-so-rarely angry—well, no one’s perfect here) older friend to younger writers when they need one. But as writers, our best friends aren’t people; they’re books. If we got along with people so well, we’d be out there among them, instead of home alone, writing. Here are some of my best friends, and the crime writing lessons I learned from them; I hope these introductions will make new friendships, and I hope these friendships will serve you as well as they’ve served me.

Less Can Be More

Horace McCoy, They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?

This tiny book, barely a novella, is a story shaved down to its perfect core, both in the language used and in the story told. Not one word is unneeded. No plot twists. No surprises. Just a straight story of a man killing a woman, as stated on the first page. And yet it’s one of the most engaging and heart-breaking books ever written. This book, with its self-assured directness, makes the other books embarrassed for dressing themselves up in double-crosses and rare poisons. Hard boiled isn’t the only way to write, and it isn’t a better way to write, but what we can learn from Horses is, with the coal cut away, how enormously brightly a diamond can shine. Read this in an afternoon and then rewrite your novel. Get rid of anything that isn’t making it better.

A Crime Novel Doesn’t Have To Be Tough

Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Crime and Punishment

A crime novel doesn’t have to be tough. It can be religious, it can be moral, it can be custard-soft and full of emotion. Some writers seem to make a game of who can have the least emotion in their books and, I imagine, their lives. There’s no law against it, but work without feeling or morals bores the shit out of me. Emotions and morals are frightening things, because they can shake our sense of self. Have courage; engage with the things that scare you; find your place in the ocean of right and wrong; feel things and believe in things and do us the favor, at risk of embarrassment and failure, of sharing them with us. Anyone can type up a few hundred pages. The real work of writing is this: reveal yourself, at the cost of pride and sanity and safety, so others can feel less alone. Dostoyevsky was not popular. If you do your job right, you might not be, either. (And yes, it’s fair to call Crime and Punishment a crime novel. Let’s make that a lesson in and of itself: there is no significant difference between literature and genre fiction beyond topic. There’s meaningful work and meaningless shit to be found on every side of the aisle. If you think crime fiction is more beholden to cliché or formula than literary fiction, you haven’t read enough of either.)

Love Your Characters

Andrew Vachss, The Burke Series

Character rules. This series doesn’t have the stellar prose style of HORSES or the sophisticated structure of Sallis’ Lew Griffith books. What it does have is an entire universe of men and women and children who are complicated, three-dimensional, often fucked-up people. Sleuth and criminal Baby Boy Burke (long story) and his crew age in real time as the series progresses: people get old, children grow up, dreams come true or don’t, relationships bloom and die, characters disappear and return, just as they do in real life. Over twenty years of reading, I came to care about these characters so much I couldn’t bring myself to read the last installment in the series. Did I mention most of my friends are books? Don’t waste your time and ours creating personified plot points to move around a chessboard: create real, rich, complicated characters. If you don’t know how to do this, you have bigger problems on your hands than learning to write: you likely aren’t listening to your fellow humans, or observing them very closely, and you are missing the heart of life on earth. Learn how to listen and learn how to see: if you can generate the patience to do so, you will be rewarded a thousandfold, as a person and as a writer.

Structure Is Everything

James Sallis, The Lew Griffin Series

Structure is a part of style, a part of story, and even a part of character. In addition to remarkable characters and killer prose, this series jumps around in time, revealing evocative moments and meaningful clues in emotional order, rather than chronological. The books aren’t organized around their mysteries; they’re organized around the detective and his inner life. This unusual structure allows for a deeper look at the titular character, detective and writer and teacher Lew Griffin. It also allows for strange doors to open in the heart and mind of the reader, by connecting things we might not have connected otherwise. Structure is a neglected aspect of the novel: stop neglecting it, and put serious thought into how to organize your book. Chronology is one possible spine, but not the only one, and even chronology has infinite complications (zoom in to slow down time, zoom out to speed it up). Read books that confuse you, crack open your preconceived notions of how to build a book, and aim from your heart.

How To Mix Styles

Rex Stout, Fer-de-Lance

I’ve learned so much from this book, and the seemingly-endless series that follows, I can barely organize my thoughts. Noteworthy thing number one: Stout beautifully mixed up two seemingly-opposed styles of mystery; the genius detective story and the hardboiled urban detective book. This book has one of each. That sounds potentially awful; it’s actually wonderful and clever and sly. Some writers cower before their influences, fearful of turning into Xerox machines. It’s usually better to accept your influences, honor them, thank them, and then fuck them up and make them your own. As with most things that scare us, you can never escape your influences: your only hope is to engage.

Noteworthy thing number two: my father loved these books, and had nearly the entire series in paperback. From fourteen or fifteen on to now, when I’ve had time to kill, I’d pick one up. I didn’t read the first in the series, Fer-de-Lance, until I was in my thirties, and when I did, I realized something strange and beautiful: none of the questions I had from reading the books later in the series were answered. I never found out how the two detectives met. Never found out the origin of their beef with Inspector Cramer, or how chef Fritz entered their lives. The series drops you into a fully-realized world of loves, hates, and double-crosses, and leaves it to your imagination to fill in the holes. Just like reality. Not everything in a book needs to be explained. Trust your reader; leave them with mysteries.

How to Bring Mysteries Into Your World

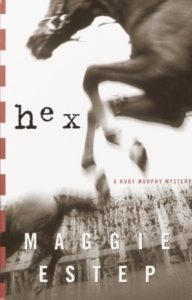

Maggie Estep, Hex

The late, great, Maggie Estep left us an ocean of beauty and art, including a trio of books about amateur sleuth Ruby Murphy. Hex is the first in the trio. In addition to her excellent prose and extraordinary characters, Maggie did something really new and intelligent in these books: she took a classic mystery story and set it in a world very much like the one she lived in. As Chandler and Hammet famously took the detective story out of the English country manor and put it where it more naturally belonged, on the streets of the American city, Maggie took the amateur sleuth mystery and put in a world she loved and understood: among poets and horse people and piano players and strippers, in Coney Island and the Chelsea Hotel. Writing evolves when we take what we love and make it our own. There is a contribution out there that only you can make. Go make it. There will never be another Maggie, but we are so lucky she left her books behind for us. Return the favor; leave things behind that no one could have made but you. Advance your art. Be brave. Get ready to be misunderstood: it’s better than being useless. Say something true.