Before a bookstore event in Chicago in November to celebrate the launch of Shell Game, the 19th V.I. Warshawski book, Sara Paretsky sat down to talk about her writing career, her inspirations and false starts, the beginnings of Sisters in Crime, pioneer journals, and much more. Only a few days later, before this conversation could be transcribed and published, Paretsky’s beloved husband, Courtenay Wright, died. At the time of this conversation, Wright had just turned 95, Shell Game had just been released, and the interviewer, Lori Rader-Day, had just become the national vice president/president-elect of Sisters in Crime, the organization Paretsky established in 1987.

Lori Rader-Day, Judy Blume, and Sara Paretsky at the Carl Sandburg Awards.

Lori Rader-Day, Judy Blume, and Sara Paretsky at the Carl Sandburg Awards.

Lori Rader-Day: The reviews of your latest book, Shell Game, are all referencing your ability to work current affairs into each of your books. In Shell Game we have the stolen antiquities, the Russian mob, ISIS, and rogue ICE agents. How does dealing in current world issues help keep your series fresh? Or is that the goal?

Sara Paretsky: I think that it actually comes out of a slightly different approach, if that’s the right word. I write what’s on my mind. There’s a wonderful Chicago writer, Carol Anshaw, whose books are very under-recognized, but she took up painting in middle age and she calls herself an autodidact, which always sounds to me like an extinct bird. But I am an autodidact as a writer. I sometimes think I would be a better writer if I actually had some training, more discipline, more focus. But I write what’s on my mind. And maybe it keeps the series fresh.

It’s sounds like it’s keeping you fresh.

Yeah. If I don’t care about it, I can’t write about it. …When I started 100 years ago, I was working full time for CNA Insurance here in Chicago and I wrote a book. I had two goals. I wanted to see if I could even write a novel and I wanted to write a novel with a woman private detective because of the issues that I had about women in fiction, which I realized once I started reading broader fiction, wasn’t confined to crime fiction. But because I was nervous and insecure and wasn’t sure I could execute, I stuck to the things I really knew, which in that case was insurance. I worked with guys in the Claims Department who—like law enforcement people everywhere—have just one hair that separates them from being on the criminal side. So they would sit around talking about the great frauds that they would have committed had they been fraudsters instead of claimant investigators.

What a gift.

Right! So I just used one of their ideas and made that the crime in the book. It was [Chicago writer] Stuart Kaminski who gave me my career. He taught a night class… called Writing Detective Fiction for Publication. I had written seventy pages of Indemnity Only, and thought I don’t know what I’m doing. It had taken me nine months to write seventy pages… Stu was enormously encouraging about the character. He gave me great advice on things I was not doing well and he also suggested since I worked in financial services and had a name there, that I make a niche of white collar crime. So in the beginning I used to follow white collar crime and financial journalism, the Wall Street Journal primarily.

And the first I’m going to say seven books were really out of that, just following the news and then turning it into books. But then I felt like I’d been in some ways telling the same story over and over. In my eighth book, Tunnel Vision, I just felt like I was painting by numbers and so I took a break and did a non-series book which in some ways was bad for my career. It cost me a lot of readers, but it was really good for my writing voice. So, I came back to VI but I sat down and thought, Oh, it’s not going to just be what’s in the news and the financial stuff. Although that continues to drive a lot of storylines, but it’s going to be more the things that I really feel connected to and passionate about.

So the first seven, eight books wrung you out—have you felt the same way since? Or have you always been able to find new ideas that give you energy?

So the first seven, eight books wrung you out—have you felt the same way since? Or have you always been able to find new ideas that give you energy?

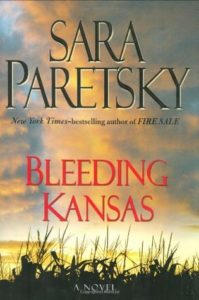

I took another break with Bleeding Kansas, another break from the series. If I had another non-VI story that I wanted to tell, I think I’m overdue for a break from her but right now, that story isn’t coming to me and so the book that I’m just starting work on is really more character-driven than some of the previous books. I mean, I’ve written five pages—no, seven.

Seven good pages…

And so that’s new for me, but they’re two characters that I—I hope I do them justice because I’m trying to build a story around them. I don’t really have a story. I don’t have a crime but I finally thought I better just start writing because I could sit stewing about for months and still not come up with a story.

Not having any crime… is that new territory to you?

It’s a little scary. I wanted to kill the superintendent of the Chicago Park District. I’m really peeved with how he’s monetizing the parks and then I thought the only story I can think of was too much off the front page which would lead me to open a libel and slander lawsuit that I wouldn’t have any defense for. I can’t get insurance anyway because I do skate pretty close to the edge sometimes. So, I’m back trying to come up with the new story. And then issues of aging, cognitive impairment, all those kinds of things are very heavy on my mind, and so I can already feel that’s going to be a significant subtext to the novel. It will just be another, cheerful, let’s-all-have-a-good-time.

Hey, people don’t pick up our books for cheerful.

Story. They want story. I think if you write books that are message-driven, you are writing very boring books, and so my primary goal is to write a story. When I read comments by writers, somebody—who was I just…Were you at the Carl Sandburg Awards?

Yeah.

Oh, right, because we were photographed with Judy Blume!

Judy Blume.

When Judy Blume said, “I just can’t not write”… I thought good for you, my sister because I’ve never had that feeling.

You think you could not write?

No, but I don’t think of it like that. I think of living in the world of stories and I don’t think of—you know, I don’t write every day. I know writers are supposed to write every day. I know we’re supposed to get up and—Mary Oliver and her poetry handbook has this whole passage on Romeo and Juliet. The Muse is like Romeo or Juliet, depending on which one you are. If Juliet hadn’t been on that balcony, we never would have had a tragedy. If you’re not there, the Muse comes and is like, mmm, you don’t care enough to be here—

I’m not going to be ready for you when you are.

So I mean, I’m very mindful about it, but I still don’t write everyday.

I will say that I don’t write every day, but I have experienced the intensity of working on something every day for an extended period of time. What I learned was that it wasn’t so much that I needed to write every day just to write, but that writing everyday kept me in the story in a way that I’m not if I’m taking the weekend off and have to figure out, OK, where is the voice and where is this story? That’s frustrating to keep falling out of the story.

Well, it is and when I’m in, when I know what I’m doing, I write with a lot of intensity, but when I don’t know what I’m doing there’s just a lot of diddling around. My office is on the third floor of my house and I deliberately don’t keep food there because it’s like: I can’t write, I need a snack. So if I want a snack, then I have to go down three flights of stairs. I write a sentence, then I get a snack. At least it keeps me nimble. But anything can distract me…and I also think every day there is a crust that I have to break through to get back to writing. So, a lot of times if I’m really in a zone and I write until I’m just too tired to keep writing, I will deliberately stop mid-sentence so that there is a place to come back to the next day because it can take me hours to get back.

I want to ask about your process. Such a boring question but I feel like everyone always loves to hear about it.

I know, I don’t understand that. I hate talking about process…When I was a child, we had a fox terrier and we had an old-fashioned—because when I was a child everything was old-fashioned—an old-fashioned cast-iron sprinkler with two arms, and as soon as the sprinkler went on, the dog is like (snarling) trying to kill it and that’s my process. I’m the dog and the story is the sprinkler.

What an image. I usually just say my process is haphazard.

I don’t outline because I just put characters in—except I don’t know for this new book, but usually I know kind of what the story arc is. I know what the crime is. I know who committed it.

That’s a lot to start with.

But I don’t know how to tell the story because the characters that I put in motion will change the story. Until they start acting I don’t see what’s psychologically probable or I may come up against a factual firewall that I just can’t reach—you know, something that I hope I could make happen, I just can’t make happen. The only time I outlined was my second book. My first book sold 3,500 copies and they wanted a second book. That was a big sale in 1982. I thought oh my god, that means I’m a writer. Writers outline so I’d better outline. I wrote this totally dead story and then I also wrote myself into a corner and I sent it to my agent Dominick, who has all the subtlety of a goat eating a tin can. I said, I can’t see how to fix this. He said it’s unfixable and unpublishable. Fortunately, I had not quit my day job selling computers to insurance agents.

Did you cry?

No, I just felt like all the wind had been knocked out of me and that I would never write another sentence again, except for promoting CNA’s wonderful products. I wrote so many sentences—

I’m familiar with that kind of work.

After six months—I shatter easily and I heal slowly, so after six months, I felt healed enough to figure out what was wrong with the book and to go back. The story was set in the Great Lakes shipping industry, and I was writing it for my husband, who had served in the Royal Navy, but kept his love at ships and shipping. We used to drive up to the Soo [the locks that help ships travel between Lake Superior and Lakes Michigan and Huron.] We used to take a week in the tail-end of summer and drive around the Great Lakes. One day we were standing near there and he said, “I wonder what would happen if you blew up one of these ships in the lock.” So, I wrote a book about that…I very much wanted to stick with the story of the ships and getting blown up in the lock. Then I saw that for me, the outline had been a killer, because I was trying to follow exactly what I was supposed to be doing. It was scary, but you know, it was my fourth book that I did what you did: jump off the high dive, quit the day job.

But I didn’t do it because I was hitting the bestseller’s list.

No, I wasn’t either. Believe me. I wasn’t a bestseller either. That happened very slowly. It wasn’t until a couple of books down the road.

So in your process, you have learned outlining, it’s not for you. Okay, that gives me a lot of hope. I feel like I’ve heard a lot of people say lately, oh, you should do whatever way you want to do it, but outlining’s the best.

I don’t agree with that. I mean, if it works for you that’s great. But I think that closes a lot of doors and can make the book more wooden than it would be if you… I mean, yeah, it’s scarier maybe to do it without an outline. It’s interesting to hear you say this because I had gotten the impression from some panel that you were on that you were an outliner.

No, I’m Team Pantser for sure. The book I’m working on right now, I did figure out more of the story than I ever have. I wouldn’t call it outlining. I just sort of figured out, and I think this might be what I’m writing, but we’ll see how it goes.

I hate the expression Pantser. This is how I categorize it: Outliners are chess players. They can think eight, ten, twelve moves ahead. I’m not. People who don’t outline are tennis players. They respond to where the ball is in motion.

That makes me seem so athletic.

Me too. I’m Martina of the mystery world.

Oh! I want to be Serena.

You got it.

I remember, I think? That you were posting [on social media] a little bit about having trouble with this book at one point. Is that true?

Yes. I mean, it is true that my methods are not…tidy. The finished book is my sixth version. I write and discard, some things get kept. When I started the book, one of the key figures in the book is a Syrian—I keep calling him a refugee, although “refugee” is a specific legal category, but he doesn’t fit that but I always think of a refugee who is seeking refuge in a war. So, he’s a refugee from Assad’s Syria. He’s a poet and I so wanted him to be a big figure in the book and I had written my first two versions, maybe fifty, sixty pages, not hundreds of pages, where he’s front and center and actually he and VI are having kind of an affair and I still mourn that, but I couldn’t make the story work around it. …He’s still is in the book, just not the way I wanted him to be, which is really frustrating. He wrote this very moving poetry, which I translated into English with the aid of a friend who actually does read Arabic… So, I started writing all of this poetry for him. He had this epic that he wrote while he was in prison. I was going to have a little couplet be the head of each chapter, and there were sixty chapters. I did ten and I thought—

Outliners are chess players. They can think eight, ten, twelve moves ahead. I’m not. People who don’t outline are tennis players. They respond to where the ball is in motion.

This isn’t going to work.

And when my English editor read it, and she said you know it’s going to make you look like George Eliot and you’re going to lose readers who come to a mystery not wanting to read George Eliot. Oh, saved.

You had a couple of false starts but that seems not unusual?

Yeah, I know, I hate it. Actually my fourth book, the one I wrote when I quit my job, it’s the only one I’ve written beginning to end without backtracking and then I thought oh I know what I’m doing. And then this book came back and bit me.

Did you imagine VI as a series character from the beginning?

I don’t know why I didn’t, but I didn’t. I was going to do this thing, and then I did it, the woman detective. I wouldn’t have made it a series if my agent hadn’t told me that he thought I should write at least three books about it. I had grandiose ideas about what I might write. I’m sort of glad, I think I would have made it a disaster, actually, but I was obsessed with Primo Levi’s story, his personal story, and I wanted to write a novel that was set—god, this is so embarrassing. I don’t know why I’m telling you. I’ve never mentioned this to another soul. But I had this whole story line worked out. I have tiny handwriting and when I’m embarrassed by what I’m saying—or not embarrassed exactly, but afraid of what people will think about it—then I write really really tiny. And I sent it to Dominick, not typed but in little, tiny print. So, it was going to be this novel set in Bassano del Grappa, in the foothills of the Dolomites, where Primo Levi was betrayed and arrested by the Gestapo. Fortunately, I can’t remember anything else about it. And fortunately, that was before word processors or computers, so there’s no record of it. Presumably Dominick long since threw out the teeny, tiny notes.

I don’t know. Maybe it’s in somebody’s files somewhere.

No, thank you. My first book came out in January and A Is for Alibi [by Sue Grafton] came out six months later. And even then, I didn’t think, oh, Sue’s writing a series. I just thought—I’m so clueless. Then it became clear that she actually had imagined this whole series and once again I thought, I’m doing this wrong, I don’t know what I’m doing. I don’t know how I’m doing it because I wasn’t imagining anything.

So what do you think about… almost twenty books later? Is it shocking to you?

It’s strange. There’s a very strange set of personalities in me—there’s my core personality which is insecure, prone to carrying grudges, nervous, worried. My big hobbies are worrying and feeling guilty. Not hobbies, but those are my big skill sets and then I would be an idiot if I didn’t say that, yeah, I’ve had a lot of recognition and I’m proud of it and that means a lot to me, but it also doesn’t exactly connect with how I feel in my core self, if that makes sense. And then there’s the political aspect of it and the political aspect I specifically mean, the feminist aspect. So for a while, you know, when I published my first book, second wave feminism was kind of cresting. We didn’t know that then, but that was ’82. I can’t remember when Sandra Day O’Connor was appointed, but it was right about then. It was the first year that women served as whole officers in the Chicago Police Department, a year earlier in New York and San Francisco. Everything just looked like it was happening. Although because I’d always been active in reproductive rights, I already could see the ominous brush back that was happening there. But—and I can still remember an argument Nicole Hollander and I had when the Ayatollah came back to Iran and overnight women’s rights disintegrated. I said, That can happen here, and [Hollander] said, That would never happen here. I think in a way she’s right and I’m right. Reproductive rights, which to me are the core of whether women are actually human and can be considered moral people who can make their own decisions about their lives and their bodies—There’s been so much roll back and people have just stood, not noticing it, until now when it’s terrifying. This MeToo era has really magnified…it’s making it very clear that things that old feminists like me, second wave feminists, thought we were really changing, have not changed. And women’s voices are still not attended to.

And so when I think of my life’s work and my novels as my life’s work and my activism as my life’s work, I think I just feel angry. And a certain amount of depression, too. I try to think of younger women, I mean people like you certainly and then the generation behind you, who are still pushing forward and being activists. There’s a saying, a Jewish saying, maybe from the Talmud. I’m not a Jewish scholar, but we’re told that the work is heavy and you must do the work, but while you are not required to complete the work, you may not walk away. I try to take constant solace from that, that it is okay if I die with things still fucked up.

[W]hen I think of my life’s work and my novels as my life’s work and my activism as my life’s work, I think I just feel angry.

Everybody dies with things still fucked up. We haven’t finished all the work on all the things that need to be worked on. I don’t think you can take on all the weariness. You can’t take all the responsibility, but you shouldn’t take all the weariness.

But I also think—my books aren’t light-hearted because I just can’t feel a light-heartedness about it.

What would happen if you did a light-hearted VI right now?

Actually I’ve been trying! VI has a downstairs neighbor who’s always pissed off about the dogs, and the other morning, the new book—the book of which I’ve written what was seven pages, but really is now six and a half pages.

Six and a half magical pages!

So, it begins with this character that I’ve just been carrying around in my head for two years and hoping now that since I’m not so bored with him that I can’t write about him—Coop, his name is. His parents, poor bastard, his immigrant parents called Gary Cooper. He has anger management issues but he’s very good with animals. He has a dog named Bear, and he and VI tangle, as we’re about to find out if I can get past six and a half pages. The book opens with her dogs, barking their heads off at four in the morning and she stumbles down the stairs past all of her apartment mates, who are furious. The Sungs on the second floor with their weeping baby and then this woman on the ground floor, Donna Liutas, who’s always pissing about the dogs and calling the cops. And so Coop has tied Bear to the lamppost outside with a note to VI: “You’re terrible with people, but you’re good with dogs and I’m leaving them with you until I get back.” And so I’m suddenly thinking of this from Donna Luitas’s point of view. Of course, how horrible to live with VI in the same building, the dogs are always barking, people break in, there are fights on the stairwell, gunshots…I started writing her, why am I the bad guy in this? But all these things are distractions because they don’t help the book, but they entertain me.

You were saying earlier about outlining and the point I wanted to make but didn’t, was that not knowing where we’re going when we’re writing helps me sit down and write because I don’t know where I’m going and I would like to know. I would like to know the story.

What a lovely way of thinking about it…

And the more I know, the more I’m, like, I don’t need to show up.

Right. Yes, yes, exactly.

I can not write. I could not write probably—at least far less than I do now. There are lots of TV shows that I haven’t seen. A lot of movies I haven’t gotten to watch. I’m a big fan of “The Great British Baking Show.” I could be watching that right now.

Oh, I love that. I never watched it, and then I was visiting friends in LA, who were fans, and I said, “Sure.” I watch lot of sporting events, and it’s like a sporting event. You root for your team and then you’re, like, oh no, they lost.

This is a weird question and I may not be asking it right. I was thinking about VI with almost twenty books now, and she was on film—which you didn’t like, is that right?

That’s right, but at the same time, it brought me to the attention of a lot of—There was one movie because it was a bad movie and it bombed at the box office, and Disney’s still sitting on the rights. But having said that, it brought me to the attention of a lot of people who had never heard of me.

And Sisters in Crime started more than thirty years ago and now has about four thousand members. I was just thinking about what is it like to see the work of your life sort of continue —when you’re still sitting right there, you’re still writing books. But it’s sort of going on beyond you, not without you—

No, it is.

I don’t want to say “out of your control” because that’s not the right word—

Well, it is. It has a different life and it has a vital life and I think… [At one point] Sisters had gotten sort of moribund, I thought it was time to dissolve it. But then around the 20th anniversary, Libby [Hellmann] and the board brought new energy to it. Since then I’m just astounded by what Sisters does. I go to those meetings at Bouchercon, and I think the work that women have done, and the work that women are doing, is so amazing. It’s so much better, bigger, and more powerful than where we were when we started and not what I had envisioned—but I didn’t have a vision per se. I had a need…

…and grudge.

And a grudge, yeah. A lot of grudges. You know, my mother had major surgery after my birth because of all the chips on my shoulders… I always feel exhilarated at those Sisters breakfasts because I feel the energy of all these women, you know, maybe each thing they’re doing doesn’t seem that big but they feel big to me. Like the Eleanor Taylor Bland Scholarship [for writers of color] feels enormous to me. I can’t use the word huge anymore.

That word is lost to all of us.

I think the library project is a brilliant project and you’ll have ideas and you’ll take it in bigger directions, too, I’m sure.

I’m nervous.

Don’t be nervous. Be just nervous enough to be keyed up.

Okay, I think we’ve talked about this before but for the sake of this public discussion, who are your role models as you got started publishing and what you did get from their example?

There were several different people in several different ways. Some like Carolyn Gold Heilbrun, Amanda Cross, when she wrote the Kate Fansler books, that was very liberating for my generation. And this was before I was even trying to write. That kind of opened a window on women’s autonomy and problem-solving capability and then a man named Michael Z. Lewen, whose books never caught on as well as I thought they should have. He had a male private eye working in Indianapolis, but he was very much a soft-boiled private eye and the gender roles were much less stereotypical.

And then there were the big boys who I was writing in opposition to. It was really reading Raymond Chandler that kind of gave me my drive to write, but because of my insecurities, and self doubt, it took me eight years to write my first book. I probably never would have written for publication. I always kept writing small things, my posthumous work, short stories and poetry—of my own, not translated from Arabic. But Chandler made me want to write a women as believable as I could make her, what that life would be like. Then somewhat later on but still early in my published career I became friends with Dorothy Salisbury Davis, who—she just isn’t known anymore. There was a time when she was really quite a major figure in American crime fiction, but she was more than thirty years older than me. We met at Hunter College—and really, this is what gave rise to Sisters because in March of ’86, Hunter College put on the first-ever conference on women in crime fiction. I was such a newbie then; I’d only published two book and was working on my third, and they asked me to be on a panel with Dorothy. I was so intense and such a prig and pain in the ass.

It was really reading Raymond Chandler that kind of gave me my drive to write, but because of my insecurities, and self doubt, it took me eight years to write my first book.

Say that more clearly for the recording—what kind of pain in the ass?

Priggish. I was so intense and Dorothy poked gentle fun at me. Dorothy had a smile that could light up all of New York City, and I fell under her spell. I learned so much from her about everything. I mean writing, and life. She was very funny in a particular way. She would often talk in interviews or panels about her first novel and that was back when there were a million publishers and the head of the house had personal relations with the writers. Scribner agreed to publish her first book. She met with Charles Scribner and they had beautiful offices on Fifth Avenue, everything beautifully paneled. Charles had tea with her and he says we’re happy to publish your book but you need a denouement. She said yes of course and ran home and looked up denouement. She didn’t know what it was.

But you know I learned a lot and even like, if a book isn’t working, Dorothy would say, turn it on its head. It sounds like unfollowable advice, except it really isn’t. It’s really that you’re looking at the things from the wrong way or the arc of the story from the wrong way. Turn it upside down and see where you’re trying to get back from, instead of writing to something.

I’m going to use that. That is something I can go home and use. Actually my last question was what advice do you have for aspiring or up-and-coming writers who are just starting now? Any kind of advice.

I don’t think my advice is very good and helpful because I think you should write what you feel passionately about. I don’t think I should write to the market and yet people write big bestsellers, by writing to the market. But why do it, if it isn’t something that you care about? Because I sold computers to insurance agents. I had health benefits. I had a nine-to-five job, sort of. And so why would you do things that are just as dull to you as selling computers to the insurance agents and not have health benefits? So, write what you care about.

Also, I think you have to learn to winnow advice, but take what’s valuable. I’ve always been writing—my whole life really—and I kind of preened. I knew how to write. I’m a good writer. Well, we all were. When we were nine years old, we were all the writing star of Miss Molly’s fourth grade class. And then you get to be twenty-something and you’re not star? Your deathless prose isn’t…? I once worked for a little company that did conferences for Fortune 1000 companies on how to implement affirmative action and the executive orders that Nixon, of all people, promulgated to put teeth into Title VII [of the Civil Rights Act, against discrimination in the workplace]. In between, we did little publications on different topics that were important Fortune 1000 managers to know about… the guy who owned the company… somehow persuaded one of [Fortune Magazine’s] senior editor, Justin Gooding, to come out and spend six months with this little company on the South Side of Chicago. And Justin Gooding had the absolute gall to take some of my prose apart and rework it. I didn’t handle it with the calm dignity that one has come to associate with me. And, bless him, instead of being as mean-spirited as he could have been to anyone and especially in a world where women get put down more than men, none of that happened. He sat me down. He said, No matter how good a writer you are, you always need an editor, and if you’re a really good writer, you need a really good editor, but you always need an editor. And so, unlike some of my peers who honked at editorial advice, I almost always follow it. With some exceptions…but when I know I have an editor who really has a good eye… When they tell me something, I listen to it because I think they have that outside eye. I may be wedded to some things in the book, but I’m not wedded to everything. And so that’s my other advice to young writers. You may not be in a position to have an editor, let alone a good editor. But there’s going to be somebody. Take their advice seriously. Don’t disdain it, listen to it. Stand up for yourself where you need to, if you’re really committed to your mission, your vision, and don’t like what being said. But don’t automatically be that—

No matter how good a writer you are, you always need an editor, and if you’re a really good writer, you need a really good editor, but you always need an editor.

Priggish pain in the ass.

I don’t know if that’s useful advice. Don’t write to the market, write what you care about, and get some of what you call a beta reader, which I don’t have any more. Courtenay was always my first and only reader, and I’m so insecure it’s hard for me to share my stuff.

One last question. What do you want to accomplish that you haven’t yet accomplished?

Well, there are books that I still want to write. You know, I wish I did write every day. There’s a YA book that I want to write set in Kansas in the 1850s and I know what some of it is but I’m nervous about it because I have never written YA. For Bleeding Kansas, I read a number of journals by pioneers, abolitionist women. Their lives were horrifying in every possible way. I mean they knew nothing about farming, about the prairies, about anything. Somebody builds these wood houses, the boards shrink from the cold weather and rattlesnakes and mice come in, and the pioneers get frostbite on their feet because they don’t realize their feet are frozen. And then they write in their journals about how they go visit each other on Sundays. Now the nearest water is a quarter-mile away, but they are inspecting each other’s linens to see if they are starched, bleached, and ironed. And I could see myself in Sophia Peckingham’s journal: Visited Miss Paretsky today. Well, we know what Jews are like, but really, could she—

Her linens were not up to snuff.

Bread crumbs everywhere, and she was actually lying in bed reading when we arrived. So an adult book about adult life, no, but a child in the 1850s, maybe. I’m not going to bore you with my story, but I sort of see it, and I really hope I write that damn book, sooner rather than later.

And then I think there are other things that I want to write, like, I really do want to write more about my Syrian poet… And then Larry Block has been doing these anthologies where he puts writers and paintings together…I don’t know anything about painting, art, but there was a painter who painted in the 20s, who did a lot of Kansas pictures. He painted this baptism taking place in a horse trough on a farm, and so I started seeing my Bleeding Kansas family in the 1990s or late early 2000s, and then the little girl in the 1850s, and then this farm and this family. I love this story. I don’t usually like my short stories because I tend to over-plot…I think a successful short story in our genre, you really have to have more mood than plot and I just always go to plot.