“The clearest way into the Universe is through a forest wilderness.” -John Muir

With a twelve-gauge slung over his shoulder and a walking stick in hand, my father cut a proud figure as he marched boldly into the eighty acres of untamed Washington wilderness that bordered our family home, four tiny offspring in tow.

He led us, whistling, down a fir-lined lane that cut a serpentine path to the heart of the forest, a path that was, to my six-year-old eyes, ripe with danger and thrills. A pile of seed studded bear scat was surrounded, prodded with the end of the walking stick and declared, “fresh”, sending chills of fear and delight down our spines. Onward we hiked, ears perked for the sound of growling behind the ferns. Around the next bend in the lane was an overgrown apple orchard, pocked with treasure (rusted cans and broken glass jugs), and deeper in, at the narrow bottom of a wooded valley, was the greatest delight of all, a muddy little river known as Salmon Creek, where we swam and ate wild blackberries until our legs were shredded by brambles and our skin pimpled with cold.

It was my first true forest ramble, and one that I remember with absolute clarity nearly thirty years later as the day that I fell in love with the woods of the Pacific Northwest.

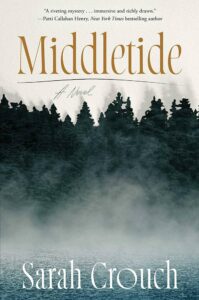

It is no surprise, then, that my debut novel, Middletide, is set there, in the small, fictional town of Point Orchards, nestled into the crook of majestic Puget Sound with dense forest at its back.

Long before I developed the specifics of the plot, I had the setting in mind, believing that the shadowy world beneath the pines of my childhood would provide the perfect backdrop for a crime novel in its emphasis of the single most compelling element in fiction: contrast.

Like most readers who gravitate toward the mystery/thriller aisle, I crave the stark shift between life and death, good and evil, and I wanted to incorporate this intertwining of darkness and light that is crucial to the genre into my own story from the very first page.

A gruesome discovery is always more shocking when it is unearthed in a beautiful setting, and there is no better way to emphasize sudden death than by dropping it headfirst into verdant life. In Middletide, the opening curtain is pulled back on two fishermen enjoying a peaceful early morning in a secluded, forest cove, only to stumble upon the grisly discovery of a lifetime.

The setting took hold early and never let me stray far during the writing process. The entire novel is steeped in a sense of place where life is indeed verdant. The forests of Washington State are thick and abundant and surprising, promising to tell their secrets around every twist in the trail, and yet never quite revealing them. Those fortunate enough to spend their real lives in the Pacific Northwest can attest to the fact that the woods will not allow their lovers to grow complacent. There is forever a new path for discovery, and when brought into crime fiction, this sense of the unknown adds to the propulsive quality that readers expect when they open any mystery or thriller.

Helpfully, and as is true with most wild places, the forests of the Pacific Northwest are well balanced in their offering of pleasures and dangers; a gift to writers who wish to flex the muscle of symbolism, building tension on the page as sweeping storms roll in off the Pacific, or dropping grief-stricken characters into the sunless days of a Washington winter. However, dismal as the weather can be at times, it is worth saying that the Pacific Northwest is far more than just the dreary, rainy Seattle painted in so many books and films. While it is true that the strip of land between the Pacific Ocean and the Cascade Mountains houses the most fertile rainforests on the continent, these woods are also rich in golden sunlight in the summer months, dotted with warm, red and orange maples in the autumn and laced with sweet blossoming wild cherry, apple and plum in the spring. In setting a story in the Northwest, the author who wishes their tome to be described as ‘atmospheric’ has the battle half won by merely describing what is already there.

This wild land also has the habit of stripping away the comfort of both character and reader. All characters are shaped by the setting an author drops them into, and Middletide’s Elijah Leith is no exception. Over the course of 90,000 words, he is broken by the land and reforged by it in the end, but not without serious struggle. For the reader, an ‘edge-of-the-seat’ reading experience is accomplished when the seed of fear is planted early and tended throughout. The very same woods that offer bounty and beauty by day bring unease by night, and when the sun sets on the page, terror grows like mold, creeping into the story and taking hold. The very woods that I romped freely during my daytime hours as a child were never to be ventured into by night. Even well into my teenage years, standing on the back porch after dark and staring out at the impenetrable wall of black forest was not done without a serious case of the ‘Willies’. The night woods are quiet but never silent, often chiming with crickets or the far-off yips of the coyote pack that claimed more than one of our cats. Nighttime in the Pacific Northwest is, in a word, spooky.

Light and darkness, delight and fear, life and death. A crime writer need only stretch out their pen and part the trees to give readers the opportunity to explore this magnificent part of the country with a twisty plotline serving as trail and tour guide. This was my aim in the writing of Middletide, to offer an invitation into a setting that is both character and anchor; a deeply rooted sense of place that tightly laces the reader to the story and keeps the pages turning.

While the forests of my youth are thousands of miles from where I live now, I have no doubt that I will revisit them over again in novels yet to be written.

***