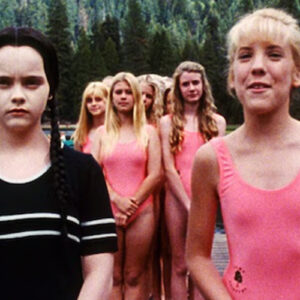

In the world famous test of visual attention designed by Daniel Simons and Christopher Chabris, an off-camera voice instructs participants to watch a short video of a group of students playing basketball, during which they must count the number of times the players in the white shirts pass the ball between themselves. Then, at the end of the game, the voice, without any further fanfare, simply reveals that the correct answer is fifteen. After concentrating so hard, the payoff feels a bit like a let-down. But then the voice asks: but did you see the gorilla?

The what?

Yup, the gorilla. Because, sure enough, during the video a man wearing a gorilla suit very clearly enters from the right, walks slowly through all the players, stops to beat his chest a little, and then continues out of the shot. And yet only fifty percent of test subjects will notice him. Fifty percent. For the rest of us, our attention is elsewhere. It’s known as inattentional blindness, the idea being that people who are focused on one thing can so easily overlook something else.

We’d all like to believe that we are reliable witnesses, and that our recall of events is credible and true, but memory and perception are slippery things, and become all the more so when filtered back through the limitations of language. All storytelling is necessarily subjective for that fact alone: two words may have an almost identical meaning, but our choice of one over another can lend a completely different weight to what is being described. Then other factors come into play: state of mind, wish-fulfilment, embarrassment, guilt, and, not forgetting, as my character Liv points out in Things Don’t Break On Their Own, ‘We all have that one story that gets slightly embellished in the retelling and, over time, the exaggerated story becomes the version we actually believe, indistinguishable from the original in our own minds.’

In storytelling, the subjectivity of perception by recollection is known as The Rashomon Effect, the name being taken from Akira Kurosawa’s iconic film Rashomon. Released in August 1950, Rashomon is a Jidaigeki (period) drama whose ideas and structure have proven so influential that The Rashomon Effect has even been quoted in court cases.

The film itself was based on a short story called In A Grove by Ryunosuke Akutagawa, and concerns the murder of a samurai and rape of his bride, critical events that are described by its four key witnesses, one of which – as told through a medium – is the testimony of the dead man himself.

But it turns out that each of these separate accounts is contradictory to the others. Evidently, for each witness – the samurai, his wife, a woodcutter, and a bandit – the stakes are high, whether that be in terms of their accountability, honour, reputation, pride or fear of retribution, meaning that each has a compelling reason to lie. As each character describes in turn a version of the events that puts their own self in the best possible light, we begin to understand what an observer means when he says, ‘It’s human to lie. Most of the time we can’t even be honest with ourselves.’

So: four different stories, four different perspectives and four different endings, but when we, the audience, have no way of knowing which one is true, whose version is to be believed?

Many stories I’ve admired have a ‘gorilla’ in their midst, that unnoticed thing that was there all along but which I’ve only managed to spot in retrospect. In thrillers particularly, as readers we expect there to be a reveal that produces an edifying moment of truth, and we all enjoy that big hit of dopamine when it comes. We want to fully understand what has occurred, have the mystery solved and the satisfaction of certitude. But what if we get to the end and still can’t find the gorilla? What if there isn’t one to find? In Rashomon, there are no easy answers. Scenes are replayed from different points of view with major differences and, as the story switches from one character to the next, the actual ‘truth’, far from being revealed, becomes distinctly more blurred.

Things Don’t Break On Their Own has several scenes that are repeated from different points of view, a dinner party in particular, and one of my biggest concerns in writing the novel was in making sure that each repeat of that scene felt fresh. That made the dinner party both the most challenging and equally the most enjoyable part of the book to write; I often had three or even four tabs open so that I could refer back to what had happened in previous versions.

Usefully, first person narrators are always going to be somewhat unreliable—they can hardly be anything else—and making use of the Rashomon Effect allowed me to have the same people see and say different things in each repeated scene. I loved playing with the idea that the evening’s events could be perceived, interpreted, and remembered by key characters in alternative ways. A significant part of the story is told through the tricky lens of memory, and my character Liv alludes to the Rashomon Effect when she says, ‘Even on a simple level, we can have wildly differing memories of a single event, where you’d be right in thinking that everyone experienced the exact same thing. Take this supper party, for instance. If in six months’ time, I asked you individually to recall tonight in as much detail as possible, it’s more than likely that you’d each give me a slightly, perhaps even a wildly different account—with variations in everything from what everyone was wearing and the order in which people arrived, to what we ate, what we discussed and who said what.’

What characters know and what they choose to reveal, what lies they tell, and what they choose to leave out—either by accident or design—is always going to be a fascinating process for a writer. This is especially true when their statements conflict with those of others, and in a story like Rashomon where such varying testimonies are left unresolved, a reader may question why a writer has chosen not to reveal which version is ultimately to be believed. But consider this: perhaps, getting to a certain truth was never the point. Rather, in writing multiple subjective viewpoints, an author may be inviting a reader not so much to seek out a factual reality, as to come to an empathetic understanding of the world view experienced by each individual character. After all, isn’t the entire point of fiction about walking a mile in someone else’s shoes? I certainly think there’s good evidence that Akira Kurosawa would like Rashomon’s audience to come to an empathic understanding of each of his character’s testimonies, as the film ends on a hopeful note, with the rescue of an abandoned baby, rain stopping, clouds parting and the sun breaking through.

In a world where the term ‘fake news’ proliferates, I think this type of storytelling has never been more relevant. It’s a plot device that creates a powerful framework for exploring events that are thorny and problematical, and especially those where the outcome is set to exact a high price from those involved. It is demanding on an audience, forcing us to address how we think about complex, ambiguous situations. It expects us to become active participants in a story rather than passive consumers of the action. We need to go away, to think, to debate, to question, to reread and rewatch. The very format turns us, the audience, into additional witnesses, and such storytelling encourages us not only to address our own bias, but to explore baseline philosophical questions, such as how can we ever really know a thing, and even whether a single truth can ever be said to exist. No wonder Rashomon is considered to be one of the most important films ever made, and its legacy galvanising. As a template for storytelling, Rashomon rejects ambivalence and forces us to think.

***