Helen Garner once described herself in the essay “Marriage” as “a small grim figure with a notebook and a cold.” In the piece, she makes her way to the Royal Mint in Melbourne to witness the day’s civil marriages, wearing an “unobtrusive black suit” that she hopes won’t show up in the background of any of the wedding photos. But she can’t help worrying her presence will be detected. “Who was that woman? I feel I have turned into the Fairy Blackstick herself: skeptical, ironic, but still, I hope, benevolent.”

The aforementioned Fairy was a catalytic character in The Rose and the Ring, William Makepeace Thackeray’s 1854 satire of monarchy, beauty, and marriage. Envisioned as something of a trickster figure, the Fairy Blackstick sets in motion all sorts of mischief and mayhem among two warring countries about to be united by marriage. Ultimately, she comes to care for the prince and princess at the center of the story, and decides to aid them in their comedy of errors.

As Garner wryly notes, the Fairy Blackstick could just as easily fit in among the crowd at the Royal Mint, there to witness those vowing to spend the rest of their lives together, buoyed by joy and unfettered by deep sorrow, or worse. I also wonder if the Fairy Blackstick isn’t also the perfect avatar for those who witness a different sort of ceremony: criminal trials, where humanity’s worst depravities, wretched tragedies, and deepest needs to live and to die are on display.

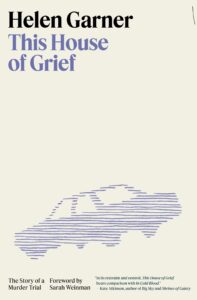

Take, for example, one of Garner’s most acclaimed and beloved works of nonfiction: This House of Grief, a searing and definitive account of an infamous Australian murder trial. What makes it such a triumph is how Garner takes the act of bearing witness to newfound levels. She doesn’t merely observe and record what happens, but invests herself fully in the process and the outcome. In doing so, she implicates herself and, by extension, the reader. Garner the journalist, the “small grim figure,” has far more agency to mold the narrative to suit her needs.

*

In December 2005, Robert Farquharson was charged with the murder of his three children, who drowned in a farm dam after his car careened off the road three months earlier. They had visited Farquharson for Father’s Day, and he was supposed to return the children to his ex-wife. Instead, the boys died as the car sank.

Farquharson’s subsequent decisions would cast him in unbearably negative light. He escaped and swam to safety without his boys, then flagged down a motorist to take him to his former wife’s house. He didn’t ensure the children had any chance at survival, and he didn’t perform the expected public displays of grief afterward. Essentially, his behavior didn’t comport with what a parent was ” supposed” to do.

Garner alights on the Farquharson case specifically because of these disconnects: between thought and action, and between the charges and the story that both husband and former wife spun in public. Could it be true that Farquharson suffered from cough syncope while driving – that he coughed so much it caused him to lose consciousness and drive into the dam? Could it be possible that his ex-wife Cindy Gambino really believed, as she said at a preliminary hearing, “that he loved his boys.” And could it be possible to love someone and yet still want to kill them? These are among the many thorny questions Garner strives to reconcile in her own mind and in those of readers.

As in her novels and her short stories, Garner proves to be a master scrutinizer in the courtroom. None can dodge her watchful eye – not even herself. After a particularly knotty and detailed cross-examination of a witness, she writes, “The material itself was intractable. It was fiddly, maniacally detailed, and catastrophically lacking in narrative. It made me – and by the looks of them, also the jury – feel panicky and stupid.”

Elsewhere, Garner turns her attention to a veteran journalist she knows, also there covering the trial, who looks at Garner wiping tears from her eyes and snaps, “I was at the funeral.”

At the time, the exchange makes Garner feel like a “sentimental amateur,” and fearful of the journalist – “it shocked me that she would not hold her fire, even for a moment, in the face of what we had just witnessed: two broken people grieving together for their lost children, in an abyss of suffering where notions of guilt and innocence have no purchase.” What we cannot know is the purpose beneath the journalist’s lashing out. Garner’s keen gaze spares no one, but it also never overreaches – nor does it push past the subjectivity of her own perspective and its biases.

No character merits Garner’s scrutiny more than the accused himself, Robert Farquharson. She makes note, during the preliminary hearing, of his “awkward and shy” smile, and then questions why she would make note of this. She chronicles his physical appearance in repeated unflattering terms, calling him a “small stump of a man, with his low brow and puffy eyes, his slumped spine and man-boobs, his silent-movie grimaces and spasms of tears, his big clean ironed handkerchief.” As James Wood wrote in his 2016 New Yorker essay on Garner’s work, “It is hard to resist the conclusion that Garner, in full maternal mode, is arraigning him for not being more o1 a man.”

But another description of Farquharson, as his defense team prepared to put on their spate of witnesses, especially stands out to me. He moves past Garner, sitting in the front row of the courtroom, and their eyes meet. She smiles, startled, and his return greeting is a “teeth-baring grimace that did not reach his eyes.” Once he was shy and awkward, but a year later, “he was a man accustomed to being stared at, and sketched by court artists, and hustled along in handcuffs. I was shocked to catch myself thinking: You poor bastard. Was there something about him that called up the maternal in women, our tendency to cosset, to infantilize? Perhaps he had made use of this all his life. Or perhaps he was trapped in it, helplessly addicted to being coddled.”

In 2021, Helen Garner published an essay in The Guardian on Janet Malcolm, the longtime New Yorker contributor and author, on the occasion of Malcolm’s recent death. Originally an introduction to the Australian edition of Malcolm’s essay collection Forty-one False Starts, Garner’s essay doubled as an ode to Malcolm’s towering influence on her work. “She seems to have been making things blossom in my head since the day I started thinking purposefully about anything,” Garner wrote. Later she concludes: “[Malcolm’s] presence in the text is lighter, her touch firmer and more delicate, and her alertness to the psychic tangles of the human more accurately attuned than those of any other nonfiction writer I know.”

Helen Garner writes about Malcolm, in this essay and elsewhere, as if she were secreted away in a Pandora’s Box, which upon opening, changed Garner’s creative life forever. And she is far from alone. Malcolm is one of my own canonical writers. She’s impossible for anyone working within and around the true crime realm to ignore. Buckets of ink have been spilled over the decades about The Journalist and the Murderer and its incisive, dry-ice-cold examination of the slippery nature between journalist and subject, but Malcolm’s superb crime writing, and in particular her courtroom journalism, extends far past her 1989 masterwork.

Subsequent crime-oriented books like The Crime of Sheila McGough (1999) and Iphigenia in Forest Hills (2011) exemplify the Malcolm mode of recounting a crime story: namely, her impulsive narrative decisions and her identification with her subjects – this growing sense that the “psychic tangles of the human” just as readily apply to herself as they do the subjects she’s scrutinizing. Crime is story, and the people caught in it are just as much characters as they are victims, perpetrators, or witnesses. Malcolm’s gaze, potent throughout, keeps the reader dancing in a daze of discomfort. Nothing is tidy, conclusions feel ready to be cracked open for new revelations, and multiple rereads are mandatory – at least for me.

The same can be said of Garner’s adroit nonfiction, and of her crime writing especially. It’s here that Garner’s ongoing conversation and deep literary debt to Malcolm emerge most clearly. For evidence, one need look no further than Garner’s choice of epigraph in This House of Grief, taken from Malcolm’s The Purloined Clinic: “Life is lived on two levels of thought and act: one in our awareness and the other only inferable, from dreams, slips of the tongue, and inexplicable behavior.”

About halfway through This House of Grief, Garner overhears several people gossiping that Robert Farquharson has a girlfriend who accompanies him to court daily. Garner cuts in and corrects them: it’s his sister, and no one can accompany a shackled prisoner. The group recoils from Garner in offense, and she’s left to wonder, “Why on earth was I angry? Did I think I owned this story?”

It’s an essential question for any journalist. Reporters are compelled to seek scoops, to glean exclusive information, to find nuggets, morsels, and connections no one else has discovered. But the Farquharson trials, and Garner’s account of them, interrogate the very nature of “owning” a crime story. Does the story of a tragedy belong to its victims? Does it belong to their families, or to those they left behind? Or does it belong to the journalist, the documentarian who translates it for the public? Can it belong to anyone at all?

If Garner arrives at an answer to her question, it is at the book’s haunting and evocative close, when she ponders the collective nature of grief. She imagines the “possessive rage” of the families, that she would dare feeling grief over the dead children despite never knowing them, never seeing them. “But no other word will do,” she writes. “Every stranger grieves for them. Every stranger’s heart is broken. The children’s fate is our legitimate concern. They are ours to mourn. They belong to all of us now.”

It’s a far cry from the “small grim figure” she imagines herself to be, the disconnect and distance between journalist and subject falling away in earnest.

___________________________________

–Author photo credit: Darren James