I grew up in the former USSR surrounded by books on shelves built by my grandfather. The books came in multiple numbered tomes – grey, brick red, pale green – and bore the names of the authors in gold lettering that glistened under the light of the lamp. Chekhov. Pushkin. Akhmatova. One collection – Tolstoy – numbered in 14 emerald-colored volumes. There were foreign ones too: the Brontës, Hemingway, London. It would be a while until I learned that such collections were a status symbol for the Soviet middle class and that they were very hard to come by. Back then, long before I became a debut author in the U.S., they were simply a backdrop – weighty and venerated.

Before I dared open one – in fact, before I even learned to read or write – I entertained myself by making up nonsensical rhymes. I loved that words could be used to build worlds. To make magic. But the words I heard adults around me use weren’t magical. They were strange, complicated, dry: synthesis, psychotechnical, methodology. My parents worked as psychologists and all their friends – and my potential role models – were psychologists too. Even Santa Claus, who came to our apartment one year, turned out to be my dad’s colleague who, after ho-ho-hoing, took off his white beard to drink vodka in the kitchen and talk shop with my dad. While I secretly wanted to grow up into someone who made magic with words, when adults leaned over to ask what I wanted to be, I dutifully said, a psychologist. Saying a writer – putting myself in the vicinity of the gods on our bookshelves – felt sacrilegious.

After living in Ukraine, we moved to Moscow where, in third grade, a tall, assertive teacher with a booming voice walked into my Reading class. He announced that instead of Reading, where we’d been suffering through short, deadwood passages of Soviet-era textbooks, he had come to teach us Literature. Literature! I still remember how that sophisticated word – and the dignity with which he said it – cast a magic spell on my mind. I thought of the gold-lettered books back home. As the teacher teleported me from the boring textbooks toward the transcendent poetry of Pasternak, I knew I wanted to be part of this World of Literature.

Within a couple of years, I was composing my own Russian poetry. On a long winter bus ride to school, I wrote a poem about Pushkin, which won an award in a school competition. When assigned to write a fairytale based on a real historical event, I wrote an animal-populated version of the 1991 putsch, a coup attempt that resulted in the dissolution of the Soviet Union. I stopped saying I’d become a psychologist and began to believe that I was on a path toward a literary future. I allowed myself to dream that I would become a novelist, with a gold-lettered tome of my own.

Then, in the summer before seventh grade, my mother dropped a bombshell: we were immigrating to the U.S.

At 13, I found myself walking into an ESL class in a public middle school in San Francisco. No one there would care for a girl writing in Russian. My main purpose in life became mastering English and fitting into the strange and fraught new world of American teenhood. I’d studied English back in Moscow, but the proper British version in my old classes included no Californian slang or cultural references. Plus, there was the accent. I’ll never forget how the whole class giggled when my “can’t” came out like “cunt”.

I learned the pledge of allegiance and the concept, drilled into me daily, that this was the best country on earth, that I was lucky to be here, and that to be American meant abandoning the past and reinventing yourself in this land of opportunity. I was, in the words of Emma Lazarus, “the wretched refuse” of my ancient homeland “yearning to breathe free.” What I heard behind the American welcome was: my homeland was lesser than, my language was unnecessary, and my past irrelevant. All those gold-lettered books that traveled with us to San Francisco were a shrine to my past. They would never be a gateway to my future.

In high school, I took Psychology where I confirmed that I had no talent or interest in following in my parents’ footsteps. By the time I got to college, I’d decided to major in Comparative Literature. I might not have the language chops or cultural knowledge to become an American novelist, I reasoned, but at least I could immerse myself in the writing of others. My classes focused on international literature and, unsurprisingly, were much smaller than the those in the English department. I read Doctor Zhivago, learned about Futurism, where we studied Marinetti and Mayakovsky, and did an independent study project on Akhmatova’s connection to Italian literature. I was finally making use of the books my mom dragged across the ocean, though I also felt college years were an indulgence. No one would pay me to do any of this in the real world.

Even if I were to write a novel, the very concept of “The Great American Novel” excluded me, I felt. Though by then I’d become a U.S. citizen, who was I to say anything about my adapted homeland? It didn’t help that I kept wondering what would have happened to me had I never immigrated. In that alternate universe, unencumbered by foreignness, was I becoming a young novelist?

At 19, I landed a summer internship at a Russian-language newspaper headquartered in the Empire State Building. As I rode the elevator – up, up, up – for a moment I felt there was value in my native language after all and maybe, even in America, I could carve out some niche and become a real working writer.

My first assignment was to interview a Soviet émigré artist who made sculptural paintings using found objects. He was in his 40s and lived in a crowded studio apartment on the Upper East Side. Though his life didn’t seem glamorous, I admired that he was able to find himself as an artist in this new country and was jealous that his craft was free of language. As I was about to leave, he asked me what I wanted to be. When I told him, he said, “To be a writer, you first need to live a little.”

Instead of seeing through his condescension and sexism, I accepted that I hadn’t lived enough real life stuff to say anything substantial. By my age, Hemingway had been injured in World War I. Chekhov had assumed full support of his bankrupted parents. Jack London had gone to Japan as a sailor, had ridden trains as a hobo, and was jailed for vagrancy in London. In comparison, my immigrant life was pretty conventional. I didn’t have the confidence to appreciate what I had already lived through: growing up in Russia during the brutal violence of the 1990s, coming to America, being separated from my father, losing my first love to a car accident, and having grandparents who’d survived the Ukrainian famine, World War II, and Stalin’s repressions.

The artist confirmed what I had already internalized as an immigrant: the stories from my culture didn’t matter.

For the next decade, I didn’t write fiction or poetry. Not a single creative word, in any language. I was convinced that I had to live a little, whatever that meant, and that I had nothing meaningful to offer to American readers except occasional articles about things happening in this country.

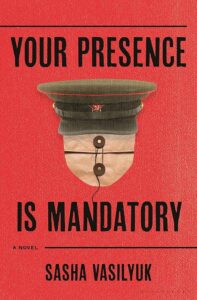

It took ten years and a divorce that sent me to Moscow where I marched in the biggest wave of anti-Putin protests for me to see that maybe I had some things to say that could bridge my upbringing in Ukraine, Russia and America. The protests were followed by arrests and, soon, by an armed conflict between my two homelands. At the time, in 2014, the conflict was centered in my family’s hometown in Ukraine. The world didn’t yet know that soon it would grow into the biggest land war since WWII.

But I knew I couldn’t wait any longer. I had to stop being afraid that I hadn’t lived enough and that no one in the U.S. would care to read a story that happens in another place, another time, to other people. It took me almost three decades to go from ESL class to seeing value in my history and culture. I only wish I could tell my younger self not to wait, but to write while life happened. To practice the craft. To record the experience of living in an insecure, confused, immigrant body. And meanwhile, not to let those old, gold-lettered books gather too much dust.

***