I had a little trouble completing this piece. It wasn’t because of writer’s block or procrastination, or the usual dog-ate-my-homework excuses writers use. Rather, it was because every time I sat down to type, someone was trying to steal my money.

I fielded five different robocalls from someone claiming to be with the IRS, looking for back taxes. I received a notification from a data broker that their servers had been breached and my Social Security number was now for sale on the Internet.

I had to cancel my debit card because someone used my number to buy clothes in Hong Kong. I got repeated texts from scammers in Southeast Asia trying to pry some kind of response out of me. And finally, I had to reset my password on a frequent-flyer account because someone was trying to hack into it.

That was over the course of twenty-four hours. One day.

Violent crime is down to its lowest level in years, but fraud is raking in billions every year. We are living in the Golden Age of Grift, where everything—from billion-dollar startups to a wrong number—can be a con.

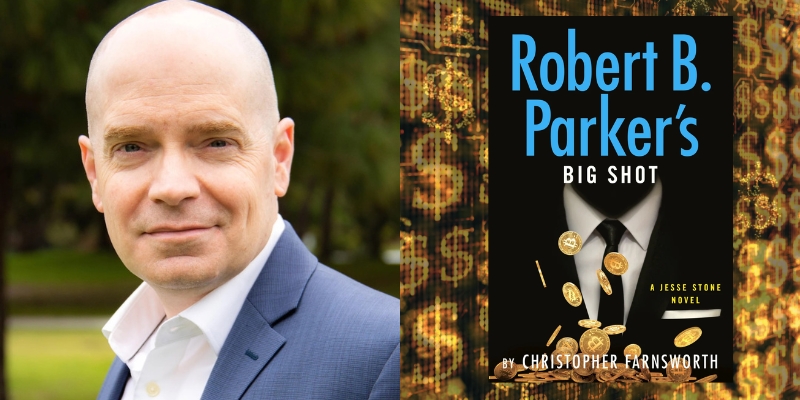

This was part of my inspiration for the bad guy in Robert B. Parker’s Big Shot. I wanted Parker’s iconic police chief to deal with one of these grifters. I wanted one of them, finally, to face consequences.

Because in the real world, it’s not happening that often.

First, there are the small scams, the ones that nibble at you constantly like starving piranhas. There are industrial-sized operations to snatch your credit card numbers, your data, and your passwords. People are recruited to work in fraud compounds where they are held prisoner while they text random numbers, trying to pry money from whoever answers.

Other con artists can create convincing deepfake voices of grandchildren begging their grandparents for money. Software available for free lets hackers crack passwords and buy stuff, apply for credit cards, and even take out mortgages in your name.

But that’s the minor leagues. If you really want to make real money, you have to think bigger.

Sam Bankman-Fried stole billions of dollars from customer funds in his FTX cryptocurrency exchange. Elizabeth Holmes of Theranos was briefly one of the richest women in the world despite knowing that her blood-testing technology didn’t actually work. Enron was one of the most valuable companies in the world until it was revealed its main product was creative accounting. Bernie Madoff had a flawless record as an investor, until his clients found out he was running a Ponzi scheme.

That is the problem we face. Until someone blows the lid off some of these operations, it’s harder and harder to tell the difference between a crime and a legitimate business plan.

For example, millions of people are investing in cryptocurrency without a very solid idea of what it is. Despite the name, it’s more a security that can be traded than actual money. Unlike, say, the dollar, which is backed by the full faith and credit of the U.S. government, the only thing supporting the value of most crypto products is the willingness of people to buy them.

Which is great as long as the cryptocurrency only goes up. But some creators of a digital coin can decide to dump their holdings, causing the value to plummet and leaving the other investors holding a worthless asset. This is called a “rug pull,” and crypto investors have lost billions of dollars to them already.

Unfortunately, the Department of Justice has decided not to prosecute cryptocurrency fraud right now. Perhaps that’s because the president and his family have their own crypto fund, and more than a billion in cryptocurrency investments.

Or maybe it’s just following the trend. Over the past forty years, under presidents from both parties, prosecutions of white-collar crimes like fraud have steadily declined, reaching their lowest level in 2025.

There’s an old saying that you can’t cheat an honest man; it implies that only greedy people get taken by these grifters, and there’s some truth to that. One employee at Theranos tried to blow the whistle on the technology’s failure; his grandfather, who was on the board and a former Secretary of State, warned him to keep his big mouth shut.

But most of the little scams rely on people’s goodwill. A guy texts you looking for his friend Jeff, and you respond. Your grandson calls, desperate for bail money, and you immediately wire him whatever he wants. You see someone on Facebook asking for money for their sick kid, and you chip in to help.

That’s the secret at the heart of every grift. They all rely on a world where someone does the right thing, where the rules still exist, but only some people follow them. It’s not genius to “move fast and break things.” It’s just forcing other people to clean up your mess.

It’s worth noting that Enron, Madoff, Bankman-Fried, and Holmes were only charged with crimes after their schemes fell apart. If they’d managed to pull in another investment round, or launched a successful IPO, maybe they’d still be on the invite list for Davos and the subject of fawning coverage in the New York Times, despite all the questionable things they did along the way.

As a newspaper reporter said during the Teapot Dome scandal, “You can’t convict a million dollars.” Imagine how much harder it is to convict a billion dollars.

So this is where we live now. We seem to be in the middle of an ongoing, worldwide divorce between actions and consequences. And only one side is walking away with the house and the car and the bank accounts.

This might explain why everyone is so angry all the time. We can blame social media and divisive politics, but it could just be the fact that everyone is tired of being treated like a sucker.

At least on the page, I can make sure that some justice is served.This is one reason I write crime fiction. At least on the page, I can make sure that some justice is served. In the world of Jesse Stone, some order is introduced again. The right people get punished, and the victims see justice done.

We could do that in real life, too. Grifters benefit from cynicism. If everything is fake, then they don’t have to worry about inconveniences like truth or rules or laws. Everything becomes negotiable.

But we let the world get this way. We can change it. We can reintroduce consequences for these actions. We can put the time and effort and resources into enforcing the law.

Until then, we’ll just have to look for justice in our stories.

***