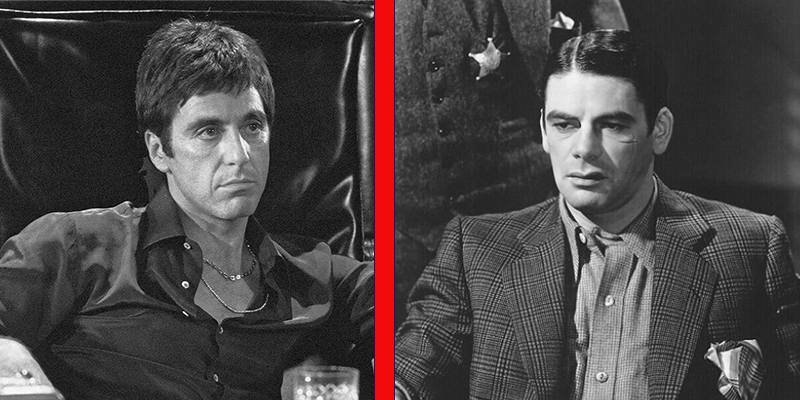

The 1932 gangster film Scarface, directed by Howard Hawks, features a moment in which a newspaper editor refers to the recently deceased mob boss Costillo as “the last of the old-fashioned gang leaders,” reinforcing “this town is up for the grabs.” The man who will eventually take over is Tony Camonte (Paul Muni), and he will eventually die because of the rampant gangster-ism that allowed his takeover in the first place. However, gangster movies also have their own cycle, and Tony Camonte, or as he is also known, Scarface, isn’t dead for too long before he is resurrected—by Brian de Palma, who remade the film in 1983, with the similar character Tony Montana as the new Scarface. Both films feature the same narrative trajectory, but de Palma’s version features several main departures that transform it from a simple remake into a serious rethinking of the original, and a meditation on the gangster genre. In the adaptation, Tony Camonte’s story shifts in time, space, and nationality—moving fifty years forward and 1,300 miles South and across cultural heritages.

The impulse to remake Howard Hawks’s 1932 gangster film Scarface came from Al Pacino himself. In an interview from 2011, Pacino recalled, “My first experience was seeing Paul Muni in the Howard Hughes film, the original Scarface that they did in 1932. It was at the Tiffany Theater here in Los Angeles on Sunset Boulevard. I went and saw that film and called Marty Bregman after. I said, ‘I think we could do this thing. There’s a remake here.’ And he, very wisely, very astutely, got out there and put the whole thing together. […] I said, ‘I gotta be that Tony Montana guy. That’s my license to live.'”

Hawks’s black-and-white film is about the Italian mob (and the rival Irish mob) mobilizing alcohol in prohibition-era Chicago, while de Palma’s film is about Cuban gangsters controlling shipments of cocaine in psychedelic, 80’s Miami. Bregman reached out to Oliver Stone, who had recently written the screenplay for Midnight Express. In his interviews with critic Matt Zoller Seitz in The Oliver Stone Experience, Stone said “I didn’t want to do an Italian Mafia movie. We’d had dozens of these things. But then Bregman came back to me and said, Sidney [Lumet] has a great idea—he wants to do it as a Marielito picture in Miami. I said, ‘That’s interesting! Sidney’s idea was a good one.”

De Palma’s Scarface is twice as long as the original and expands on themes explored in Hawks’s film. It does not remove anything. Therefore, the 1983 film Scarface is a cultural update to its precursors, adapting the original movie, and modernizing it, while still preserving the original’s overall thematic intent. Adaptations have lives separate from the rest of cinema, turning their “parent” films into comparative devices, the reflexive-ness of which permits an articulation of something extremely old, and entirely new.

This act of “updating” salvages themes and intentions across different adaptations and does not interfere with both films’ main goals of communicating cultural criticism—goals which are articulated even before the films begin, on printed statements before the credits. The title card of the 1932 film reads,

This picture is an indictment of gang rule in American and of the callous indifference of the government to this constantly increasing menace to our safety and our liberty. Every incident in this picture is the reproduction of an actual occurrence, and the purpose of this picture is to demand of the government: “What are you going to do about it?’”

The title card then flickers, and new message appears; “The government is your government. What are YOU going to do about it?” Thus, the 1932 Scarface has the intention of a siren—to alert both officials and civilians about a threat with the power to harm society that exists within society. The 1983 Scarface also begins with a problem that both contextualizes the film and presents a source of conflict. Its title card reads,

In May 1980, Fidel Castro opened the harbor at Mariel, Cuba with the apparent intention of letting some of his people joining their relatives in the United States. Within seventy-two hours, 3,000 U.S. boats were headed for Cuba. It soon became evident that Castro was forcing the boat owners to carry back with them not only their relatives, but the dregs of his jails. Of the 125,000 refugees that landed in Florida, an estimated 25,000 had criminal records.

Therefore, the 1983 Scarface focuses on the very specific concern of Cuban immigrant criminals. Across the Scarfaces, there is a migration from North to South, but also a dilation from a large, shapeless thug population to a specific, statistically expressed infestation by a single people. In keeping with the agitation expressed in their title cards, the films rely on the performance of real events to instill awareness and concern in audiences. Thus, the 1932 version depicts such real atrocities as the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre, while the 1983 version includes real-life footage of Fidel Castro and the Mariel boatlift. Furthermore, both films rely on the real-life, criminal issue of trafficking—but the illegal substance has changed; the alcohol smuggling in the original, and in history, is a kind of gateway drug for the cocaine smuggling that emerges in the 1983 adaptation and its corresponding cultural moment.

Similarly, while Scarface is essentially the same character in both films, his background is changed; he is drawn the same way across the two, but colored in differently in each. Tony’s scar, for example, is in virtually the same place across both of his faces—and both times, when he is asked about it, he gives an ambiguous answer. It does not matter how he has become Scarface, as much as it matters that he is Scarface, a figure who comes to stand out from the crowd—a mold to be filled. Anthony “Tony” Camonte, though, is an Italian Scarface in a cultural moment when his nationality does not matter beyond its association with the mob (the known existence of Italian gangsters such as Al Capone, whose nickname was “Scarface”). Scarface is born again in 1983 as Antonio “Tony” Montana, a Cuban immigrant—because in the early 1980’s, the Mariel boatlift brought many Cuban criminals into the country, and because the emergence of Latin American drug cartels (operating largely from Colombia) at the end of the Cold War became a national concern. Therefore, a Latino Tony is a generalized amalgamation of two cultural “problems,” and not based on one concrete example; the film smashes together two contemporary social concerns to create a more fictional Scarface than the Capone-esque one.

Both films, however, have cast Tony with an actor who does not share his heritage. Paul Muni (born in the region of Austria-Hungary that is now the Ukraine) plays the Italian-accented Camonte, while Italian-American Al Pacino plays the Cuban Montana. As committed to their accents as these actors are, it is audible that they are not of the nationalities they play. This consistency reinforces the adaptation Scarface as performing the original, but also calls into question the importance of Scarface’s cultural origins. In the 1932 Scarface, his mother has a thick Italian accent, Tony’s accent is less pronounced but still there, yet his younger sister Cesca speaks like a perky, fast-talking All-American gal. This is confusing, but nowhere is it explained where Tony Camonte was born. In the 1983 film, Montana’s mother and sister Gina have thick Cuban accents—having immigrated to the United States (before he did).

Therefore, Montana’s rise to power is more of an immigrant’s deranged pursuit of the American dream than Camonte’s quest for riches and power. The 1983 version reflects the worry that someone from somewhere else can enter the United States and take over or wreak havoc; Montana migrates over, and then climbs up. This, plus the 1983 version’s alignment of the Mariel boatlift with the 1932 film’s angry appeal for civilians to protest the government’s inefficient regulation of problems in the county, illuminates the main social problem in de Palma’s film’s not as gang violence or cocaine trafficking—but, rather problematically, immigration.

The film is xenophobic on its own, but it also attempts to undertake xenophobia as a theme, muddying its overall sympathies and concerns. The film’s attempt to critique xenophobia is expressed immediately—the first shot of the movie has Montana fiercely interrogated in English at an Immigration office. The officers, whose faces are chopped off by the camera’s suspicious, lingering revolution around Tony’s face, are surprised that he can speak the language so well, but still insensitively and disinterestedly accuse him of lying and smuggling and send him to “Freedomtown.” These officers are clearly represented as racist. “They all sound the same to me,” says the head officer about the Cubans he has spoken to, ordering Tony out. This scene, contrasted with the same moment in the 1932 version, where Camonte is interrogated in a police station and the question of nationality is never an issue, presents his immigration into the United States as a problem even before it becomes apparent that he is, actually, a dangerous criminal. Montana has to transcend oppositional cultural barriers just to get to America, and still faces them after he has arrived.

The adaptation of Tony’s love interest—the glaring, frowning, rail-thin blonde with a low-cut neckline—also transforms prejudice in the first Scarface into racism in the second. Poppy, the girlfriend of Camonte’s boss, is initially not interested in Camonte because he is poor; he grows on her when he begins to make money. Elvira, the 1983 counterpart, is originally averse to Montana also because he is poor as well as an immigrant. “I have enough friends, I don’t need another one,” she tells Tony, when he informs her that he would like to be her friend, “Especially one that just got off a banana boat.” A few seconds later, when they begin to argue, she snaps back at him, “Hey, José.” Poppy and Elvira are exactly the same character (in both films, for example, Tony needs to buy a new car to impress “her”)—but Elvira’s dialogue has been manipulated from Poppy’s to include a kind of modern, “white,” ignorant, agitation directed at immigrants. But, overall, in its ultimate representation of the immigrant Montana into a slimy crime boss, the film ultimately presents a case study in which white racist anxiety about immigration is represented as not entirely misplaced. In this way, the 1983 Scarface is a giant contradiction in a way that the 1932 film is not.

As Poppy does in the 1932 film, Elvira, too, warms up to Montana after he has made a lot of money; as the neon sign flashing “The world is yours” (on a blimp and then replicated on a statue in Montana’s home, and on a flashing billboard outside Camonte’s living room) predicts, Scarface does “get it all.” He also loses it all, at the pinnacle of greed. In both conclusions, he takes up a weapon to fight against the angry hoards invading his house, and his demise is spat out by the skinny mouth of a machine gun, and he collapses in close proximity to the flashing sign.

Therefore, regardless of the films’ interaction with their zeitgeist’s sociopolitical agendas and trepidations, the villains who represent the problem are ultimately defeated; when the Scarfaces end, the Scarfaces meets their ends. However, as cinema’s cyclical story-consumption reinforces, the Scarfaces (movies and archetypes alike) are always evolving, just as much as America’s own attitudes towards those it perceives as outsiders.