They fanned out across the slope, taking their time to survey the terrain. The wind was no longer so ferocious, but it was still cold and gusty. Back home, the experts referred to this as a natural ‘terrace’, but it was far from flat – a thirty-degree slope with steep cliffs at the bottom, the terrain a mixture of scree-covered rock and patches of snow. Just one slip could send you tumbling down the mountain, to be smashed to pieces on the glaciers below.

They were at 27,000 feet on the North Face of Everest, the lower edge of the ‘death zone’. Five American climbers and mountain guides: average age thirty-two, two previous summiters, all eager and willing. At Base Camp, 10,000 feet below – near the tip of the Rongbuk glacier – other members of their team were attempting to follow the action through a powerful telescope.

It was 1 May 1999, day one of their search for Everest’s Holy Grail: a camera that had gone missing seventy-five years earlier when George Mallory made his final, fateful attempt on Everest. No one expected to find anything straight away – it was all about assessing the lie of the land, getting used to the oxygen sets and radios, figuring out how to work together as a team for a mission that was expected to take a week.

And then, fifteen minutes in, Jake Norton, the youngest climber on the team, spotted something: a blue oxygen cylinder, much bigger and heavier than their own, possibly a remnant of a Chinese camp set up in 1975. If it was, they were in the right area, so they carried on going, spreading out until eventually they were so far apart they needed their radios to communicate. Each of the climbers had been given a small, spiral-bound notepad with instructions on how and where to look, but the search zone was vast – the size of about twelve American football fields – so they followed their hunches and intuition. If a body had fallen from a ridge high above, where would it have landed?

Were there any obvious funnels or collection points?

Then at 11.00 a.m., about half an hour in, Conrad Anker spotted the first corpse, a twisted set of badly dislocated limbs wrapped in a washed-out purple suit. One arm stuck out rigidly, almost as if it were waving. Getting closer, he realized that the ravens had been there first, pecking off much of the skin from the dead climber’s face. It was a gruesome sight, but it wasn’t what he was looking for, the corpse clearly too recent.

‘What are you doing way out there?’ one of his teammates crackled over the radio. ‘We need to be more systematic.’ Anker ignored him and carried on going westwards. This was sacred ground, the North Face of Everest – mountaineering’s most elevated and celebrated peak. All around were features named by previous expeditions; it was a privilege just to be here, heading for the Great Couloir that Edward Norton had attempted in 1924 and Reinhold Messner had conquered in 1980.

Then Anker saw a second body, this time in a blue-grey suit; again it was a confusion of broken limbs, the torso facing downhill. But like the first, the clothing was too modern for the expedition they were interested in. So Anker moved on, keeping a wary eye on the line of cliffs below until he stopped to take off his crampons. They weren’t much help on steep downward-facing slabs covered in unstable scree.

A few minutes later, he spotted a piece of fabric fluttering in the wind and began climbing upwards to investigate. Blue and yellow, it too was probably modern but he needed to get closer to check.

And then he noticed it: a patch of white. Not snow, not rock; something that didn’t quite fit. He moved closer and was stopped in his tracks. It was the powerful shoulders of a climber, his arms stretched upwards as if to arrest a fall, his partly clothed body seemingly fused into Everest itself.

Moments later, Conrad Anker took out his radio and called his teammates, but it was another twenty minutes before they all assembled, staring down at the mummified but clearly defined body. No one could quite take it in. On the first day of their search, Anker had discovered something totally remarkable, the solution to a mystery which had gripped the climbing world for the last seventy-five years. He’d found the remains of one of the great heroes of twentieth-century exploration: George Herbert Leigh Mallory.

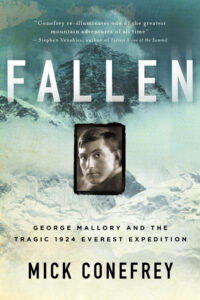

In the now almost a century since he disappeared into the clouds with his young partner Andrew Irvine, George Mallory has become a legendary figure. Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay may have been the first men to reach the summit of Everest, but their expedition has never quite roused the same devotion in Europe and America. Mallory has inspired biographies, epic poems, documentaries, works of fiction as well as works of fact, and countless magazine articles and other commentaries. His answer to the question ‘Why climb Everest?’ – ‘Because it’s there’ – is probably the most famous quotation in the history of exploration, on a par with Henry Morton Stanley’s ‘Dr Livingstone I presume’ and Neil Armstrong’s ‘A small step for Man’.

Everything about Mallory, from his looks to his skill with words to his athletic abilities, made him the ideal, quintessentially English hero. Even his name seemed to imply his destiny: George the dragon-slayer; Mallory an imperfect echo of Thomas Malory, the great chronicler of Arthurian legends. It’s no wonder that his friend Geoffrey Winthrop Young dubbed him ‘Galahad’, after the legendary knight.

In general, most biographers and commentators have been very positive about him: he’s portrayed as a Romantic hero, the incarnation of adventure, an idealist and a visionary. The only real exception to this hagiographic tendency comes in Walt Unsworth’s monumental history, Everest, in which he described Mallory as someone ‘who had greatness thrust upon him. The pity of it was that he had so little actual talent.’ I suspect that Unsworth was being deliberately provocative, but a century after Mallory’s disappearance how should we assess him? Was he the ‘greatest antagonist that Everest has had – or is likely to have’, as Edward Norton dubbed him in the official account of the 1924 expedition, or was he ‘a very good stout-hearted baby’, as Tom Longstaff, his teammate on a previous Everest expedition, memorably described him in a private letter?

Is there any fresh evidence that might help answer this question? The unexpected truth is that over the last decades a surprising amount of new material has become available – Mallory’s letters to his penfriend Marjorie Holmes, John Noel’s private archive, George Finch’s papers, an enormous number of documents from the Mount Everest Foundation archive that have now been scanned and digitized – that enables Mallory’s story to be told more fully. The picture that emerges is complex and nuanced: a fascinating individual, loved by his friends and family; idealistic, chaotic, narcissistic, generous, impulsive, indecisive, driven by the demons of risk and ambition, and continually reassessed and reappropriated by successive generations of climbers and adventurers of all kinds.

This book is not an attempt to tell the complete story of Mallory’s life. Rather, the aim is to do two things: first, to look in detail at the events of 1923 and 1924 and understand the forces that drove Mallory and the third British Everest expedition, and second, to separate the man from the mythology that grew up after his disappearance and which continues to evolve, especially after his body was discovered in 1999.

It begins though, not on the slopes of the world’s highest mountain, but on a small spit of rock by the seaside…

___________________________________